This story appeared in the June issue of the PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door monthly? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

The Mississippi riverfront in New Orleans is no stranger to change. The course of the river itself moved many times before arriving at the present crescent. The vantage afforded by that bend in the river, coupled with the ease of access to Lake Pontchartrain via Bayou St. John, famously inspired the city’s founding by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bievnville. Only three years later, the engineer Adrien de Pauger oversaw construction of the city’s first earthen levee; though just a few feet high, it marked the first in a litany of human-made changes that continues today.

Commerce drove many of those changes, as New Orleans became the nation’s transshipment depot. Today, river transport remains an economic mainstay, but technological and commercial changes have freed miles of riverfront for new uses. Several proposals have been made to alter or repurpose the Mississippi waterfront. The combined effect of these proposals could alter the city’s most historic neighborhoods for a generation.

Imagery (c)2019 Google, Data SIO, NOAA, U.S. Navy, NGA, GEBCO, TerraMetrics, Landsat / Copernicus, Data LDEO-Columbia, NSF, NOAA, Map data (c) 2019 Google

Photo by Liz Jurey

Commonly known as the Industrial Canal, the Inner Harbor Navigation Canal linking the Mississippi and Lake Pontchartrain was begun in 1918 and finished five years later. Louisiana authorized its construction by the Port of New Orleans on the heels of the opening of the Panama Canal.

The long-imagined water link between the lake and river had eluded New Orleans for two centuries because of the engineering challenge presented by river levels 10 to 20 feet above those in the estuarine lake. An early 20th-century engineering marvel, the lock, constructed where the canal meets the river, raises and lowers vessels.

St. Claude Avenue crosses the lock on an integrated Strauss heel trunnion bascule bridge that raises with help from a large counterweight. It is one of three along the canal and just a few remaining in use nationwide; these bridges were named for their inventor, Joseph B. Strauss, who went on to become chief engineer on the Golden Gate Bridge.

Following World War II, the Industrial Canal gave rise to a yet more ambitious canal, the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet. Completed in 1968, MRGO required more dredging than the Panama Canal and destroyed 20,000 acres of wetlands. This 75-mile link to the Gulf never produced the economic benefits predicted; instead saltwater intrusion continued to kill off cypress swamps east of New Orleans, and the eroded channel infamously funneled storm surge into the city when Hurricane Katrina made landfall in 2005. A barge struck the Industrial Canal wall unleashing a devastating torrent into the Lower 9th Ward.

In the documentary “Locked,” urban ecologist Dr. Josh Lewis says, “The vision of the inner harbor — of relocating the port into this area — is one of the biggest failures in American urban planning history.” The MRGO is now blocked by a rock dam and the massive $1.3 billion IHNC-Lake Borgne Surge Barrier, and the Industrial Canal primarily serves barge traffic on the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway. Buoyed by talk of infrastructure investment by the Trump Administration, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has revived a 1990s plan to replace the lock to accommodate larger vessels, convening a Section 106 consultation earlier this year, as required by the National Historic Preservation Act.

On May 22, the New Orleans Coalition and Citizens against Widening the Industrial Canal held a forum on the proposal, at which flood risk topped a long list of concerns. Bridge closures and a decade of construction promise to worsen traffic already subject to delays by drawbridges and trains. Coupled with pile driving and construction noise, the negative effects could stifle investment in these historic neighborhoods if the project gets federal funding.

Our take: It is imperative that lawmakers revisit alternatives to this billion-dollar project and examine the costs and benefits with a focus on St. Bernard and Orleans parishes.

To understand the history and politics behind the development of the Industrial Canal, view the short film “Locked” here.

Advertisement

Photo by Liz Jurey

At Erato Street, the Port of New Orleans opened its first cruise ship terminal in tandem with the 1984 Louisiana World Exhibition. Since that time, New Orleans has become the nation’s sixth largest cruise port, adding a second terminal at Julia Street and serving more than 1 million cruise passengers annually. A majority of these are Caribbean-bound non-locals spending at least one night in New Orleans, according to the Port NOLA Strategic Master Plan.

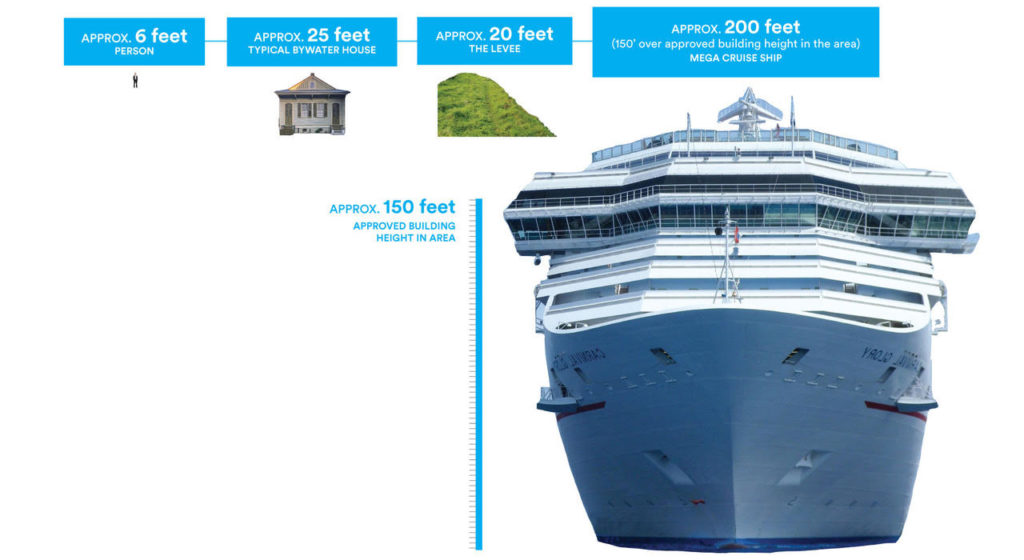

The size of cruise ships has ballooned along with the cruise industry: Today’s “megaships” tower more than 200 feet above the water line, rendering them unable to pass beneath the Crescent City Connection bridge. A 2013 plan, Reinventing the Crescent, that helped catalyze development of Crescent Park also included speculative renderings showing a new cruise terminal at Poland Avenue near the former Naval Support Activity complex, also known as the Port of Embarkation.

In 2016, when the port undertook a multi-million-dollar wharf stabilization at Poland Avenue, officials told both The Times-Picayune and The New Orleans Advocate their long-range plan was a cruise terminal at that site. This met with fierce opposition from Bywater residents, who rightly point out that a megaship docked at Poland Avenue would tower nearly 150 feet above the maximum allowed building height on their side of the levee. The associated noise and light pollution would be worsened when cruise ships disgorged 5,000 passengers en masse into a phalanx of taxis and ride-share vehicles.

“Why are they creating endless problems and destroying a functioning historic neighborhood when there are far better sites just 10 minutes away in St. Bernard Parish?” asked S. Frederick Starr, owner of the nearby circa 1826 Lombard House and author of a book chronicling its restoration. “In the end, this project pits tourism against a settled and functioning residential community. It’s bad public policy and bad economics.”

The 2018 Port NOLA Strategic Master Plan is bullish on cruises — projecting as many as 1.9 million passengers by 2030, necessitating a third cruise terminal — but noncommittal on sites, saying only, “A number of potential sites for this development are being evaluated both on existing Port property and off, where feasible.”

Our take: Parking jumbo cruise ships in the Bywater is tantamount to out-of-scale development and sure to tax both residents and infrastructure. The Port should seek appropriate alternatives for the Poland Avenue wharf.

Photo by Infrogmation New Orleans

In a widely touted swap finalized last year, the Port of New Orleans acquired the Public Belt Railroad from the city of New Orleans in exchange for wharves at the foot of Esplanade Avenue and Gov. Nichols Street. Those wharves represent the missing links in a green corridor that includes Crescent Park, the Moonwalk and Woldenberg Park. The city’s decision to hand over development of the wharves to the Audubon Commission, however, proved more contentious.

Rumors of a concert venue or other fee-based amenities generated an outcry, prompting Audubon Nature Institute President and Chief Executive Officer Ron Forman to tell members of the Vieux Carré Property Owners, Residents and Associates and the Faubourg Marigny Improvement Association: “What we’re hearing is a need to be passive in what we do. … We’ve heard that loud and clear.”

The Audubon Nature Institute, which operates the Audubon Aquarium of the Americas, the Audubon Zoo and Woldenberg Park on behalf of the Audubon Commission, subsequently conducted a series of public meetings and launched a website, riverfrontforall.org, to gain citizen input on how to program the new park. A cooperative endeavor agreement provides $15 million for construction of park facilities, $9 million of which will come from the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center. It’s the estimated $2 million to $3 million in annual maintenance costs that Forman cited as potentially necessitating a revenue stream from concessions or activities within the new park. New Orleans residents, who recently approved a restructured millage for parks and recreation, now wait to see how the Audubon Nature Institute will respond to their ideas for a new park on a historic stretch of river.

Allen Johnson, president of Faubourg Marigny Improvement Association, said Marigny residents already cope with traffic associated with attractions in the French Quarter and along Frenchmen Street. A venue on the river, like a cruise terminal downstream, would only spike congestion in neighborhoods wrestling with oversaturation by tourists. Conversely, he noted, many residents will welcome the transportation choices presented by a contiguous riverside bike and pedestrian path to the Central Business District.

Our take: Free public green space and trails between Crescent Park and Woldenberg Park will serve tourists and locals alike. Concessions should serve park patrons, not compete with nearby entertainment venues.

Advertisement

Photo by Liz Jurey

During their antebellum heyday, 3,000 steamboats arrived per year in New Orleans. Nineteenth-century engravings and early photographs show paddlewheelers lining the wharves of the East Bank, great plumes rising from their twin smokestacks and their decks groaning with cotton.

Today, the Steamboat Natchez plies the river laden with tourists, local schoolchildren and wedding parties. The Natchez’s new sister ship, the City of New Orleans, is also a modern vessel that takes its name from an early 18th-century precursor. Where exactly it will dock, however, is a matter of contention.

The New Orleans Steamboat Co. has proposed to dock the boat at Woldenberg Park upriver from the present Natchez dock. This would necessitate construction of a metal gangway and would obstruct views from the popular Riverwalk Gazebo. In a letter to the City Planning Commission, the Louisiana Landmarks Society noted: “The proposed gangways and guard rails, along with the docked boat, don’t just limit the view, they obstruct it. … The proposed spot on the riverfront currently provides one of the most beautiful vistas looking out onto the Mississippi. … Certainly there is a location that has less impact to the public resources that would be more appropriate for this business.”

The Vieux Carré Property Owners, Residents and Associates has joined the call for the commission to reject a conditional use permit and thus force the operator to find a less conspicuous site. “Increasing the number of vessels that are permanently docked on the river will, bit by bit, decrease the overall access and enjoyment of the public riverfront,” said VCPORA Executive Director Erin Holmes. “This is in direct contradiction to goals stated in the city’s Master Plan of increasing public access to waterfronts, particularly along the Mississippi River, and ensuring these spaces are not dominated by specialized uses or private facilities.”

Our take: Additional details and public meetings are needed to determine a more appropriate docking location.

Photo by Adrian Cotter

After delays and repairs, two new ferries are soon to begin crisscrossing the Mississippi River between Algiers and the foot of Canal Street. The vessels will replace aging ferries built in 1937 and 1977.

The long-awaited upgrade to the aquatic assets of the Regional Transit Authority will include a new ferry terminal on the East Bank and substantial refurbishments to the existing Algiers Point terminal. A controversial design for the East Bank terminal was shelved in late 2018 after ferry riders complained about a detatched pedestrian bridge next to the Audubon Aquarium of the Americas and bids came in higher than expected.

The newest iteration for the East Bank terminal calls for keeping the existing pedestrian bridge over rail and streetcar tracks but constructing a new ramp to replace long defunct escalators. City Councilmember Kristin Giselson Palmer, in whose district both terminals are located, praised the changes, saying, “This is 150 percent better than what was originally proposed,” according to The Times-Picayune. The newly constructed structure on the river side of the tracks is anticipated to be completed in 2021, soon after the nearby World Trade Center is reopened as a Four Seasons Hotel and residences.

Our take: Preservation of the existing East Bank pedestrian bridge was a win for riders and proof that new isn’t always better — or cost effective.

Nathan Lott is Preservation Resource Center’s Advocacy Coordinator and Public Policy Research Director. He can be reached at nlott@prcno.org.

Advertisements