This story appeared in the September issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

Segregation on the Lakeshore

Lincoln Beach abuts Lake Pontchartrain in the Little Woods neighborhood of eastern New Orleans. Founded as a segregated black swimming area in the late 1930s, the site underwent a major renovation in 1954. Thereafter, until its closing in 1964. Lincoln Beach provided a summer long festival of water sports, carnival rides, music and food for families living under the oppression of segregation.

Lincoln Beach typified the problems of the separate-but-unequal era. Acquired by the Orleans Parish Levee Board in 1939, the lakefront site was designated for use by Black families, who were forbidden from gathering or swimming along other parts of Lake Pontchartrain’s shoreline in New Orleans. Lincoln Beach stood 12 miles from the Central Business District down a two-lane road with no public transportation. Sandwiched between fishing camps, the site contained one building. Over the years its beachfront fell victim to erosion and sewage. All of that stood in stark contrast to the then-whites-only Pontchartrain Beach, which boasted 50 easily accessible acres and a $100,000 roller coaster ride.

Things changed in the late 1940s. Social worker, union activist and civil rights leader Ernest Wright and his People’s Defense League organized voter registration campaigns that increased black electoral participation. Under the administration of Earl K. Long, whom Wright supported, the Levee Board unveiled plans for a $1 million renovation of Lincoln Beach. Pile driving ceremonies took place in the spring of 1953.

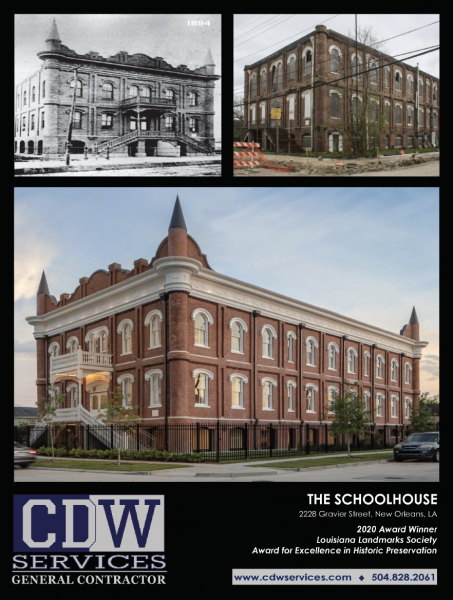

Advertisement

On May 8, 1954, Wright chaired the new Lincoln Beach’s dedication ceremonies. On the dais sat the Rev. Avery Alexander, the Rev. A.L. Davis, Dillard University President Albert W. Dent, Orleans Levee Board President Louis Roussel and top state and city leaders. Gov. Robert Kennon viewed Lincoln Beach’s redevelopment as an example of Louisiana looking after “all of her citizens.” Mayor deLesseps “Chep” Morrison used the occasion to promise a trade school for African Americans and development of the Pontchartrain Park subdivision for the Black middle class. Wright saw the 17-acre expansion of Lincoln Beach as a “step forward in the Negro’s fight for first-class citizenship.”

On May 28, 1954 at 9 a.m., manager Walter Wright threw open the gates. Eleven-year-old Paul Castille bought the first ticket and then led thousands onto a midway lined with shrubbery as Papa Celestine’s Dixieland Band greeted the crowd with lively jazz. In place of the barren landscape and solitary building of old, the new Lincoln Beach contained a bathhouse with 2,000 lockers. Pools matched the specifications of Pontchartrain Beach’s pools. Barges brought in white sand to expand the beachfront to a quarter of a mile in length.

Every week thereafter, advertisements in the Louisiana Weekly newspaper beckoned residents to “Take a dip day or night” and “Relax in the cool summer breeze on Lake Pontchartrain.” Families and church groups look advantage of the picnic shelters, carnival rides and supervised swimming activities. Couples dined on the Carver House restaurant’s outdoor roof terrace, attended the “Dance Under The Stars” on Friday nights and took romantic strolls down the moonlit beach. Outdoor entertainment over the years included The Bob Ogden Orchestra, the Hawkettes, pianist Walter “Fats” Pichon, The Ink Spots, Earl King and Fats Domino. On Thursday nights, WMRY Radio’s Larry McKinley hosted free midway dances.

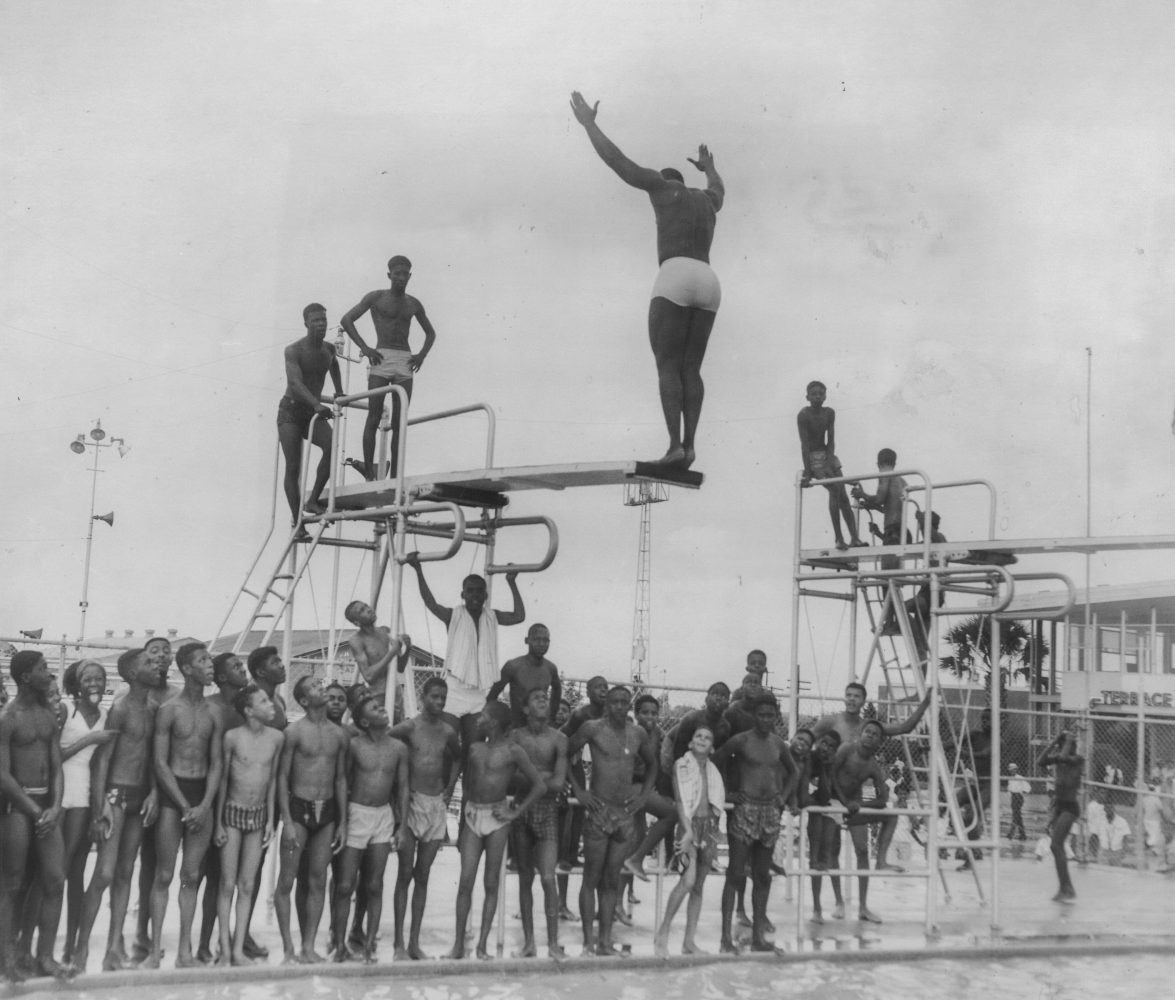

On Friday mornings, scores of buses unloaded hundreds of day campers. They donned their swimsuits, raced through a cold water shower alley and plunged into Lincoln Beach’s gigantic three-to-six-foot deep pool. There, a generation of New Orleanians learned Red Cross swimming safety and engaged in swim meets.

Photo 1 courtesy of the State Library of Louisiana, Photo 2 courtesy of the New Orleans Public Library.

In the adjoining 16-foot-deep pool, Lincoln Beach provided a rare opportunity in the Deep South for black divers to hone and display their skills. Crowd favorite James “Pump” Chatman conducted coordinated team diving stunts from the 10-meter board.

Lincoln Beach ended 1954 with a month-long competition for the title of Miss Lincoln Beach. McDonogh No. 35 High School student June Foster won, receiving a 50-inch gold-plated cup, a dozen roses, a music scholarship and gifts from Phil Werlein and the People’s Defense League. To top it off, Jet magazine published a photo of her receiving a kiss from Nat King Cole, who served as master of ceremonies.

In the years that followed, Lincoln Beach lured Southern travelers, calling itself the “Coney Island of the South.” In 1956, a 3,500-car parking lot opened along with new rides, and in 1958, Wright organized a Negro State Fair at Lincoln Beach with themes of music, youth and labor. (The popular Wright received nearly 40,000 votes in a 1960 campaign for lieutenant governor of Louisiana.)

Then, with the passage of the Civil Rights Bill in 1964, Lincoln Beach met the fate of segregated lunch counters and water fountains. Despite its uniqueness in the Deep South and the memories it created, the beach’s facilities, accessibility and amusements had never reached the level of Pontchartrain Beach. Historical and market forces prevailed. Attendance dropped dramatically, and Lincoln Beach closed in the autumn of 1964.

Today, the skeletal remnants of the beach’s amenities sit in ruins.

Keith Weldon Medley is a New Orleans historian, photographer and author of the books “We as Freemen: Plessy v. Ferguson” and “Black Life in Old New Orleans.” An earlier version of this article was first published in Preservation in Print in 1999.

Read more:

City assesses the feasibility of reopening Lincoln Beach, the historic waterfront park built during segregation

New Orleans residents remember Lincoln Beach

Advertisements