Preservationists universally writhe at the building. Visitors startle at how its hard lines clash with historical wooden motifs. Local urbanophiles excoriate it as precisely the sort of oversized development they oppose, and recount how its 1970 construction helped galvanize the improvement association which today mobilizes the opposition. Indeed, no one except its inhabitants seems to have nice things to say about the Christopher Inn, that big boxy apartment building on Washington Square Park in the Faubourg Marigny.

The project does, in fact, have redeeming qualities, and they come to light upon understanding the site’s history and the cultural heritage of the surrounding neighborhood.

At the turn of the 19th century, the site, now 2110 Royal and at the time immediately downriver from the lower city limits, formed part of the plantation of Bernard Xavier Philippe de Marigny de Mandeville. With New Orleans poised to grow after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, Marigny saw an opportunity to profit by getting into the urban real estate market. He hired engineer Nicholas de Finiels to design a plat in 1805, and surveyor Barthelemy Lafon to lay out the block in 1806. Finiels’ arrangement featured, among other things, a grand boulevard paralleling a circa-1740s sawmill canal — today’s Elysian Fields Avenue — adjoined by a park, today’s Washington Square.

Faubourg Marigny in the early 1800s developed as an inner suburb with mixed residential, institutional and light-industrial land uses. Its largely working-class population comprised what local historian Henry C. Castellanos described in 1895 as “Europeans of Latin extraction and of Creoles, white and black,” the latter both free and enslaved in antebellum times. Starting in the 1830s, Irish and German immigrants settled in Marigny in substantial numbers, as did smaller populations from the Mediterranean and Caribbean regions.

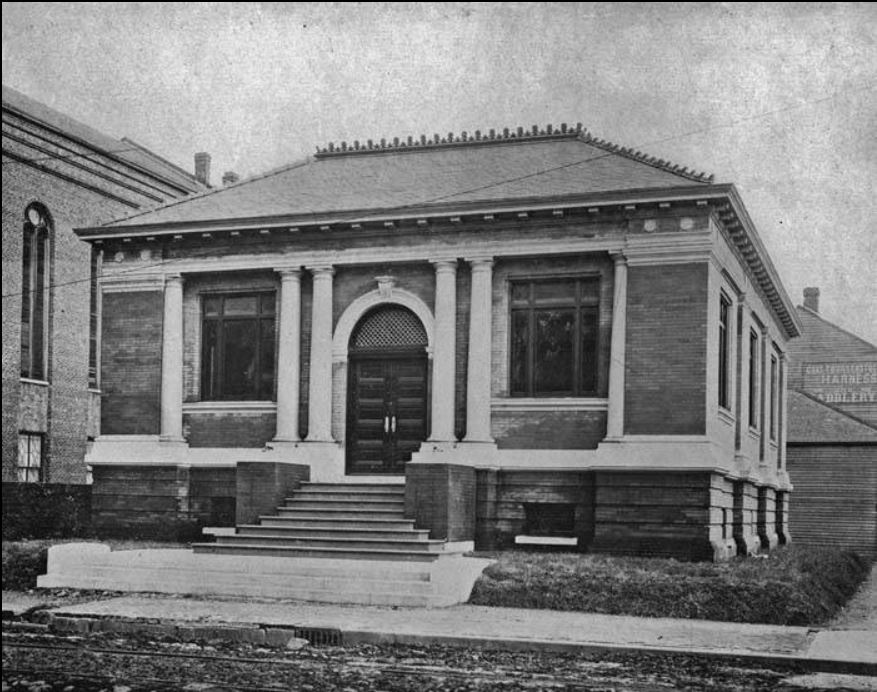

- The Carnegie Library on Washington Square Park. Photo courtesy Wikipedia

- Third Presbyterian Church on Washington Square, with French Market in foreground, circa 1906.

Anglo-Americans also poured into New Orleans, and more often than not, they settled on the upper side of town, over a mile upriver from the Faubourg Marigny. Nearly all were Anglophones; most were Protestant, including Presbyterians; and many of them were of Scots-Irish ancestry. The growing community found itself in need of a church, so with the aid of the Connecticut Missionary Society and the leadership of Rev. Sylvester Larned, the uptown faithful formed the First Presbyterian Church in 1818. Over the next 40 years, the congregation erected a sequence of imposing Gothic churches on their parcel overlooking Lafayette Square (see my June 2015 Preservation in Print article for a history of these structures). In 1845, others in the uptown community formed a Second Presbyterian Church on Prytania and Calliope, which would later merge with yet another uptown congregation in the 1860s.

There were also some Presbyterians who bucked the trend and settled downtown, in the lower faubourgs of the predominantly Catholic and francophone Third District. To serve them, a minister named Frederick Stringer established around 1840 a Presbyterian Sabbath School staffed by missionaries. They soon found their sessions filling up with locals as well as transients en route from the Northeast to the newly independent Republic of Texas. For whatever reason — perhaps Texas’ pending statehood, or the forthcoming war with Mexico — “some of these [migrants] tarried in our city and [eventually] made their homes here,” as a 1937 church history pamphlet explained.

The informal sessions continued in temporary spaces on nearby Moreau (Chartres) Street at Elysian Fields, and on Esplanade Avenue at Burgundy. Finally, “on the 7th of March, 1847…the Third Presbyterian Church of New Orleans was [formally] organized with a colony of 18 members of the First Church.” For the next decade, Third Presbyterian members met in a small frame provisional church of 150 seats erected on Casacalvo (Royal) below Esplanade for $2500, while church leaders sought a site for a permanent building.

They eventually purchased a parcel further down on Casacalvo, overlooking Washington Square, an apt complement to the uptown congregation’s scenic perch on Lafayette Square. Architects Albert Diettel and Henry Howard won the design commission in 1858 and proceeded to create a solid auditorium-style church, with meeting rooms in the raised basement and, on the piano nobile, a sloping floor and angled pews facing the nave and alter. The exterior brickwork was intricate in the German fashion, while the fenestration and details of the 43-foot-high walls paid homage to Gothic and Romanesque motifs. The design’s most conspicuous feature was the central tower and spire rising around 90 feet. With a budget of $45,000, the construction firm Little and Middlemiss got to work. On January 1, 1860, the Third Presbyterian Church opened for services.

For the next six decades, despite Civil War and postbellum turmoil, the Third Presbyterian Church formed a community cornerstone in the hard-scrabble Third District, with Sunday services upstairs and everything from lectures to recitals to festivities in the basement. In 1902, the church got a new neighbor when an adjacent apothecary and Chinese laundry were demolished for the Andrew Carnegie-funded Royal Street branch of the New Orleans Public Library, one of six “Carnegie libraries” built in the city. The church, meeting room, park, and library together made 2100 Royal a vital civic space.

Structurally, the church weathered well the region’s many tempests, including the Great Storm of 1915, which toppled 11 church steeples citywide. Nevertheless, “a rumor has spread,” according to the New Orleans Item, that the Third Presbyterian’s “tower and spire are in danger of falling, [leaving] some neighbors…panicky.” They might have been more than rumors: photographic evidence indicates that the spire, though not the tower, had been removed by the early 1920s.

By this time, the congregation recognized that many families with children had moved out of downtown and toward Bayou St. John, to be near the new Presbyterian Mission Sunday School. To be closer to both its congregants and the school, leaders decided to relocate the church to a convenient site on Esplanade Avenue. In August 1919 they sold their 60-year-old Washington Square landmark plus an adjacent house to the Catholic Archdiocese for $15,000. The property would become the Holy Redeemer Catholic Church, “under the administration of the Josephite Fathers, an order which devotes itself,” as the Times-Picayune reported, “to the evangelization of the negro race.” The racial designation reflected the recent decision by the Archdiocese, echoing what had been going on in secular society since the end of Reconstruction, to segregate its churches into white and black congregations.

Archbishop John Shaw dedicated the church in a January 1920 ceremony followed by a parade, and for the next 45 years, Holy Redeemer served as a cultural bastion for Catholic black Creoles in a neighborhood historically dominated by their ancestors, and in part built by them. The house next to the church became the Josephite rectory, and the Holy Redeemer School was established a few blocks away on Dauphine at Touro.

Hurricane Betsy put an end to all this. The September 1965 storm wreaked astounding damage on the 105-year-old church, completely obliterating its side walls and roof but strangely leaving its tower intact, though dangerously leaning. The rear wall also remained standing, such that the large crucifix behind the altar could be seen from the park. The Carnegie library was also heavily damaged, and both buildings as well as a neighboring house were soon razed. For the first time since plantation days, Royal Street by Washington Square lay mostly vacant.

Yhe Archdiocese decided not to rebuild Holy Redeemer, and while its school continued to operate on Dauphine, many families decided to join St. Augustine Church or other predominantly African American parishes in the Sixth, Seventh, and Eighth wards. The New Orleans Public Library, too, decided not to rebuild its branch here, given the area’s demographic decline. The neighborhood had even lost its name, its historical moniker “Faubourg Marigny” having gone the way of the French language. Tourists in this era were routinely advised against crossing Esplanade Avenue, the other side deemed too divested or too dangerous.

Enter at this point Father Phillip M. Hannan. Appointed to head the Archdiocese of New Orleans shortly after Hurricane Betsy, Archbishop Hannan noted the Catholic Church ran only three residential homes for the poor and elderly — a paltry 260 beds in aging wooden structures, despite that hundreds more rooms were needed, especially since Betsy’s floodwaters had left many indigent elders practically homeless. To address this pressing community need, Archbishop Hannan in 1966 created Christopher Homes, Inc., a nonprofit housing agency owned by the archdiocese, and proceeded to gather resources. An ideal site for a first major project, Hannan reasoned, would be the archdiocese-owned Holy Redeemer site, given this area’s aging population, the park across the street, and its proximity to the Betsy-flooded wards. Adjacent parcels were purchased, and in March 1970, construction began on the Christopher Inn, a nine-story, $2 million apartment building with 147 units renting for around $100 a month to senior citizens earning under $5,000 a year.

The architects opted for an Internationalist Style because it was in vogue at the time. There was no reason not to go with a bold new aesthetic: the neighborhood had no historic-district zoning, nor did any other areas outside the French Quarter, and many locals likely welcomed the new investment and modernization in this crumbling precinct.

Only a small number of architectural historians and preservationists found the Christopher Inn to be an oversized intrusion. But their numbers were growing, and their argument was winning over more and more citizens. In 1971, Tulane preservation architect Prof. Eugene D. Cizek led a pioneer study of the Faubourg Marigny — there was a concerted effort to revive the historical name — and advocates eventually attained zoning limits to prohibit buildings on the scale of the Christopher Inn. In 1972, the Faubourg Marigny Improvement Association (FMIA) formed, and by decade’s end, “the Marigny” had earned both national and local historic district designations. Many of its old buildings by the 1980s and 1990s had been researched and documented; Washington Square was restored; and the renovation of the neighborhood’s hundreds of historical houses — and the gentrification of its population — steadily proceeded.

It’s in this context that redeeming qualities may be found in the Christopher Inn. Its brand of Internationalist Modernist architecture, whatever one may think of it aesthetically, has come and gone, and more so with every passing day, its occurrence in the cityscape may now be considered genuinely historical. The building’s scale, described as “oversized” and “malproportioned” by the New Orleans Architecture—Creole Faubourgs volume, is not entirely without precedent in this area: a hundred years ago, a sprawling brewery with a six-story dome operated only one block away, while the extant Claiborne Electrical Station at the foot of Elysian Fields and the Old Rice Mill farther downriver, also over a century old, have comparable massing. Indeed, there once stood an elder-housing complex in present-day Bywater which covered four solid acres, had triple the number of apartments as the Christopher Inn, contrasted stylistically with the surrounding neighborhood, and had twin four-story crenelated towers breaking the riverfront skyline. Known as the Touro Almshouse, the Gothic landmark stood for only three years before burning in 1865.

Even if one considers the Christopher Inn to be an architectural intrusion, the project transforms into a gem when one views it through a cultural lens. Inside this seemingly stark structure reside over a hundred elders, of all racial and ethnic backgrounds, who possess a treasure trove of social memory and local knowledge. Some have neighborhood roots going back to antebellum times, with passed-down stories to match. Most are native-born in a neighborhood that’s now transplant-dominant, and nearly all are on fixed incomes in an area that has become decidedly upscale. The operation itself represents the endurance of a centuries-old local religious legacy in an area that is now mostly secular. As a major source of affordable housing in an otherwise costly real estate market, the Christopher Inn is also a bulwark against super-gentrification, a refreshing alternative to the empty pieds-à-terre of the lower French Quarter, and a source of genuine social diversity in a neighborhood that purports to celebrate it.

Those who view the Christopher Inn as a defeat of structural preservation should try viewing it as a triumph of cultural preservation. Doing so softens those hard lines, and suddenly the edifice does not seem so intrusive.

Epilogue: The last Third Presbyterian Church, designed by Diboll & Owen and built in 1924 at 2540 Esplanade Avenue, finally closed its doors in 2004 for want of a congregation. As for the original 1858 church on Washington Square, architectural historian Robert S. Brantley points out that its façade and proportions were “practically identical to that of the First Presbyterian Church in Port Gibson, Mississippi, built a year later.” Famous for its unique gilded steeple-top hand pointing to heaven, that church is well worth a visit to historic Port Gibson, between Natchez and Vicksburg.