This is an edited version of the author’s “Cityscapes” column that first appeared in NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune on Jan. 31, 2016. It was updated and and reprinted in the June issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine with permission.

From the blazes that destroyed century-old houses around New Orleans to the flames shooting from the roof of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, recent news stories call to mind the vulnerability of our historical architectural treasures to fire. Students of urbanism should take heart that New Orleans has a record of responding to fiery disasters with sound policies and shrewd revitalization. A number of examples come to mind.

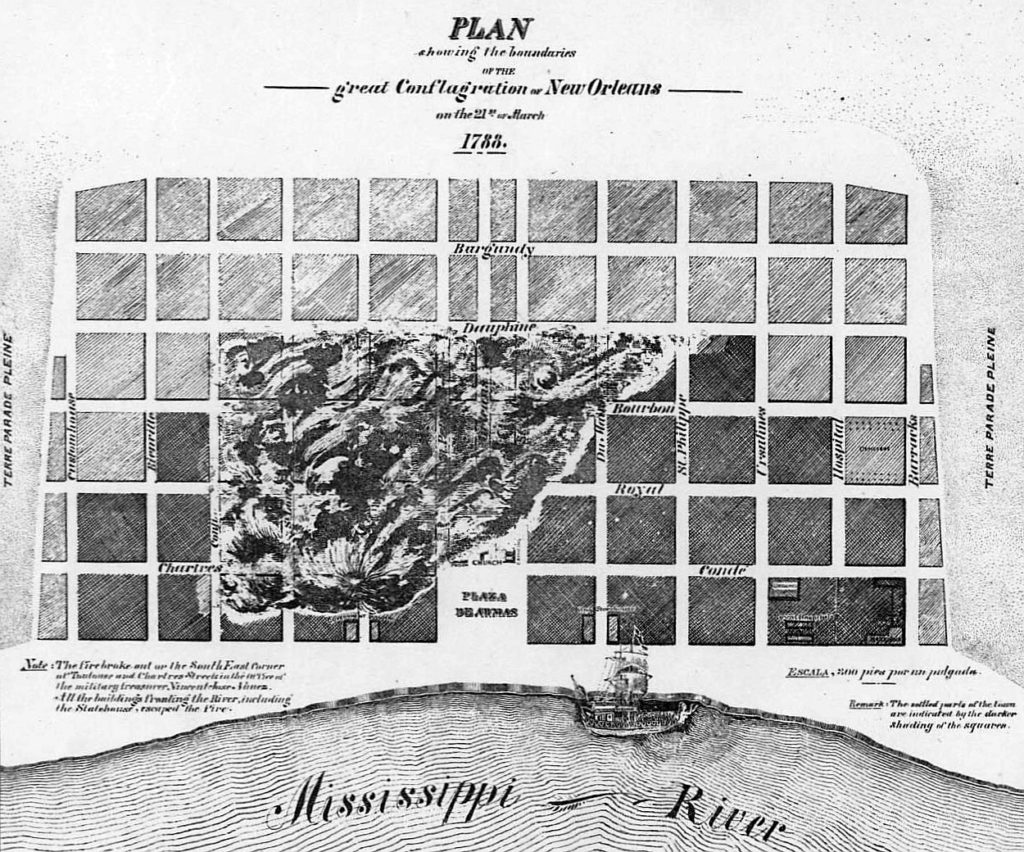

The first came on Good Friday in March of 1788, when a votive ignited a curtain and torched the house on the corner of Chartres and Toulouse streets. Dry winds swept the flames into adjacent structures, and by late afternoon, according to the records of the Spanish Cabildo (city council), “4/5 of the populated section of this City was reduced to ashes.” The losses included 856 “fine and commodious” houses, mostly of the West Indian-influenced Creole style dating to French colonial times, with cross-timbered walls and double-pitched roofs.

It was a terrible blow to the tenuous colony, and the recovery proceeded in fits and starts. But thanks to the leadership of Governor Miro, the provisioning of food and shelter to the homeless by the Cabildo, the fiscal generosity of private benefactor Don Andres Almonester y Roxas and the easing of trade regulations, the city averted the shrinkage and divestment that sometimes follow urban traumas.

In fact, the disaster created occasion to expand the footprint of the ruined city. (In 2005, there was the opposite suggestion to shrink the urban footprint in the wake of the Hurricane Katrina deluge.) In 1788, a new subdivision was laid out in the adjacent Gravier plantation as the Suburbio Santa Maria, later known as Faubourg Ste. Marie or St. Mary (the American Sector) and now the Central Business District. A construction boom ensued citywide, and the new edifices generally continued the West Indian Creole architectural tradition. Changes in Spanish policy in response to the 1788 disaster focused on fire suppression rather than prevention, as authorities requested from their superiors “four pumps…60 leather buckets…two hooks with a chain…rope…and six hooks with long wooden handles.”

Area burned in the Good Friday Fire of 1788. Courtesy Library of Congress.

All this changed six years later, when on Dec. 8, 1794, boys playing in a courtyard lost control of a fire to southerly gusts, and the flames ignited adjacent wooden houses. Three hours later, the conflagration had consumed 212 structures, most of them all of a few years old.

This time, the Spanish dons responded by endeavoring not only to suppress fires but also to prevent them, and they looked to their own building traditions to do so. Cabildo records state new houses “must be built of bricks and a flat roof or tile roof,” and “two story houses…should all be constructed of brick or lumber filled with brick between the upright posts, the posts to be covered with cement, (plus) a flat roof of tile or brick.” Extant houses had to be strengthened “to stand a roof of fire-proof materials,” and their wooden beams covered with stucco. “[All] citizens must comply with these rules whenever they wish to construct a new building,” declared the Cabildo.

It is difficult to evaluate the efficacy of the 1794 architecture codes, given the change of dominion to the United States after the Louisiana Purchase (1803) and subsequent rapid urban grown. But it is quite true that post-1794 urbanism would impart a more solid brick countenance to the city, in the tradition of Spanish colonial cities — more along the lines of a Havana or Cartagena than the semi-rural wooden village that was French colonial New Orleans.

Fire remained an eternal fear throughout the 1800s, as suppression efforts, limited to the range of steam pumps, could not keep up with the increasing height and spread of the built environment. Hotels — and there were plenty of them, this being a city of transients — were especially vulnerable, and famed examples, such as the St. Charles, St. Louis, Verandah and others, were all burned and rebuilt multiple times.

Advertisement

Some blazes flattened entire blocks. On the night of Feb. 16, 1892, amid what the Daily Picayune described as “a ceaseless procession (of) merry, happy” people patronizing “saloons (and) restaurants,” a fire started in a store on Canal at Bourbon. Flames “crossed [Bourbon] street in a bound” and enveloped half the block. Crowds fled; steam pumps arrived, and plumes of water arched into the sky. By morning, both sides of the 100 block of Bourbon were reduced to smoldering embers. Damages exceeded $2 million, and 13 major businesses were destroyed. Coincidentally, this same block had burned just two years earlier, on Mardi Gras night 1890, but this time was much worse.

Like many disasters, this one created opportunity. Owners of the burned lots on the lake side of the street found they had an eager buyer in the form of famed Canal Street department store D. H. Holmes, which purchased the now-open parcels at the corner of Customhouse Street (now Iberville) and expanded its enterprise onto Bourbon. “Holmes’s” would have an illustrious history on both sides of this block for the better part of a century to come, enabled by the 1892 fire.

Owners of the river side of the Bourbon ruins, meanwhile, had an equally eager neighbor: the fancy new Cosmopolitan Hotel on Royal, whose owners envisioned a valuable second entrance on Bourbon. They purchased the parcel of a burned-out piano store, cleared the wreckage and commissioned architect Thomas Sully to design an annex.

Sully’s design would rise seven stories high and boast an imposing granite façade with a grand entrance on Bourbon Street. As the tallest structure in the vicinity, the enlarged Cosmopolitan Hotel would attract a steady flow of moneyed visitors, who in turn would accelerate the formation of a nocturnal entertainment district in the upper French Quarter. New enterprises specializing in food and drink opened nearby, among them what is now Galatoire’s (1905).

1: This scene captures the gaping hole in the 100 block of Bourbon Street caused by the 1892 fire. Courtesy Richard Campanella

2: The Cosmopolitan Hotel annex, the seven-story building facing Bourbon Street, was built after the 1892 fire.

The Cosmopolitan’s success ushered in a new era of handsome high-rise hotels appealing to affluent leisure travelers, among them the Grunewald (1893) on Baronne Street (now the Roosevelt), the Denechaud on Perdido Street in 1907 (now Le Pavillon) and, five years later, the Monteleone, towering 12 stories above 200 Royal St. and family-owned to this day. By 1920, 20 additional elegant hotels were operating in downtown New Orleans, while the older exchange (business) hotels, such as the venerable St. Charles, adapted themselves to the new leisure market.

All the competition would cost the Cosmopolitan its marketplace advantage, and it would eventually fold. But we may credit it today with catalyzing the rise of luxury lodging and laying the groundwork for the modern tourism industry, just as the hotel itself was catalyzed by the opportunity availed by the 1892 Bourbon Street fire.

Three years later, at 12:45 a.m. in the windy darkness of Sunday, Oct. 21, 1895, a fire of unknown origins started in a crowded Morgan Street tenement in Algiers. Northeasterly winds fanned the flames beyond the control of local firefighters, who found themselves with insufficient hoses and pumping capacity. By dawn, 10 blocks of Algiers were charred utterly, leaving only what one observer described as “a forest of chimneys.” At least 193 houses were destroyed and dozens more damaged; 1,200 people were homeless. Losses were estimated at $400,000, or $11.4 million in today’s dollars, and there was no government disaster relief to help those without fire insurance.

What did exist, however, was a generous civil society. New Orleanians formed a Relief Committee and, through churches and social institutions, secured food and shelter for the homeless. In the ensuing weeks, nearly $16,000 in donations was raised, or $457,000 in today’s dollars — enough, along with insurance claims ($300,000 or $8.5 million today) and other aid, to get victims back on their feet.

As for the cityscape, recovery was amazingly speedily. The fire had occurred during the height of the Progressive Era, when urban citizens put a premium on new infrastructure and municipal improvements. New Orleans was no exception, and Algiers benefited especially. Its streets were paved; houses were electrified; a waterworks plant was built to resolve pressure problems; a viaduct was installed to decongest riverfront activity; and a new Moorish-style courthouse opened and serves to this day. New Victorian houses with exuberant gingerbread were erected in such numbers that, by late 1896, one proud resident reported that “a walk along those attractive streets makes it difficult to realize that this was the same so lately in ashes and ruins.” A similar stroll today is a living lesson in 1896-style urbanism, and it is quite beautiful. One might be tempted to say that if Algiers had to burn, it chose a good time.

Advertisement

The same may be said of Salaville in Westwego, at the opposite end of the West Bank. Sala Avenue had become the region’s “cannery row,” lined with facilities processing shellfish coming in from the Barataria Basin on the Company Canal. On April 14, 1907, a fire broke out near Durac Terrebonne’s Fishermen’s Exchange and spread via northeasterly winds and an abundance of wooden building materials. Neighbors formed a bucket brigade, but it was futile. By noon, 42 buildings had been destroyed, and up to 600 people were left homeless.

Like Algiers, Salaville promptly rebuilt, for there were livelihoods to be earned. The new blocks of Salaville flourished, and the cannery industry boomed. Among the first structures rebuilt was Durac Terrebonne’s Fishermen’s Exchange, which currently houses the Westwego Historical Museum.

There are more recent examples of deadly fires prompting judicious changes. To wit, the 1972 Rault Center fire on 1111 Gravier St. killed six people, some falling to their deaths on live television. But along with a rash of similar high-rise fires across the nation, the Rault Center tragedy led to the establishment of what is now the United States Fire Administration and the writing of architectural codes for fire sprinkler systems and other prevention/suppression measures. Uncounted numbers of lives have been saved by these regulations.

One year later, on the corner of Iberville and Chartres in the French Quarter, a terrible new local record was set. One summer night in 1973, a jilted customer set a fire in the stairwell of the gay-oriented Up Stairs Lounge. Thirty-two patrons found themselves trapped on the second floor and perished amid smoke and flames, ranking as the deadliest fire in New Orleans’ history. While the tragedy brought forth no specific changes in regulations or the cityscape — if anything, some officials and the media tended to be flip about the calamity — the Up Stairs Lounge fire did serve as a reminder of the perils of crowds in spaces not up to fire code, where marginalized groups oftentimes find themselves congregating.

There are plenty of exceptions to the pattern of infernos igniting improvements, and we should not be so naive as to believe that disasters “wipe the slate clean” and allow us to finally “get things right.” The burning of the Old French Opera House in December 1919, for example, formed an irreparable blow to the francophone Creole population of the French Quarter, and the site on the corner of Bourbon at Toulouse remained a weedy lot until 1965.

Indeed, on any given street in impoverished areas today, one can find all too many charred ruins and blighted houses waiting to catch fire, all of which only exacerbates the decline of a neighborhood. Clearly other key factors must be at play for revival to rise from ruins, including capital, proximity to vibrant areas, good architectural bones, civic support, and most importantly, a visionary with a good idea.

Richard Campanella is a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture and the author of “Cityscapes of New Orleans,” “Bourbon Street: A History,” “Bienville’s Dilemma” and other books. Campanella may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, or @nolacampanella on Twitter.

Advertisements