This story appeared in the March issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

At 12:45 a.m. in the windy darkness of Sunday, October 21, 1895, a fire ignited within a crowded Morgan Street tenement known as The Rookery in the West Bank neighborhood of Algiers, New Orleans. Northeasterly winds fanned the flames throughout the two-story common-wall apartments, sending a dozen poor, mostly Italian immigrant families fleeing for their lives. Among them were the wife and children of Paul Bouffia, who operated a fruit stand at 307 Morgan where the fire apparently originated.

An alarm was sounded, and three horse-drawn fire trucks arrived promptly from the Engine 17 House on Pelican Avenue. Firemen operating the largest steam pump set its hose into the river, while the other two pump crews tapped into ground wells within a block of the fire. Streams of water arced into the orange glow, and spectators breathed a sigh of relief.

But because it had been a dry autumn, the wells “were emptied of water (within) half an hour,” wrote local historian William H. Seymour in 1896, leaving the river pump alone to douse the rooftop flames. They ignited adjacent houses beyond the pump’s reach, and by 2:00 a.m., the 300 block of Morgan and both sides of 200 Bermuda were one gigantic bonfire visible for miles.

Chief Daly of the Algiers Fire Station called for help, but it took a solid hour for larger pumps to arrive via ferry from downtown. By that time, the fire had consumed the Eighth Precinct Police Station and the Algiers Courthouse, located in the century-old Duverjé Plantation House, along with most of 200 Morgan. Reams of records dating to colonial times added fuel to the fire, and “when the old roof fell in,” wrote Seymour, “it sent up a shower of sparks…windward” into the next tier of doomed houses.

1. The 1895 fire originated in a unit of a tenement at 307 Morgan, center, and eventually destroyed 10 blocks. Photograph by Richard Campanella.

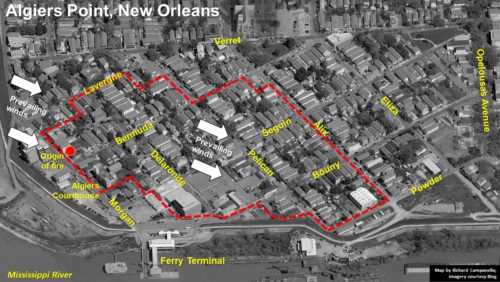

2. Aerial photo of modern Algiers Point overlaid with footprint of area destroyed by 1895 fire. Map by Richard Campanella; aerial photo courtesy BING.

Realizing the blaze was now beyond control, Algierines frantically removed valuables from their doomed houses and carted furniture down to the batture, even as tank trucks and their skittish horses struggled to run relays from the river to the pumper trucks. Mayor John Fitzpatrick and his police and fire chiefs saw firsthand the sheer inadequacy of their resources: wells too dry, pumps too weak, hoses too short, firemen too few, and fuel too plentiful, in the form of wooden houses and stockpiled coal and firewood — all in the face of that fateful wind.

Some would later blame the disaster on Algiers’ low prioritization from City Hall (the neighborhood had been annexed into New Orleans in 1870, but remained village-like and isolated from the urban core), a complaint still heard today. Others blamed the firefighters. “The principal causes of the rapid spread of the flames were not only the scarcity of water and a furious wind,” wrote the Picayune, “but the poor work of the fire department. When they lost control of the fire they became demoralized.”

The blaze next consumed both sides of 300 Delaronde, then 300 Bermuda, followed by 200 and 400 Delaronde, most of 100-400 Pelican Avenue (including the fire station) and 100-300 Alix — plus all the intervening streets of Bermuda, Seguin and Bouny down to Powder.

Viewed from downtown, the conflagration must have made for a frightful sight, spanning a quarter-mile at its widest point with hundred-foot-high flames licking the night sky.

Three factors explain why the fire did not destroy all of Algiers. For one, alert operators of the nearby Hotard & Lawton Saw Mill activated their steam pumps and, with a 1,300-foot hose tapping into unlimited river water, were able to soak rooftops and save everything downriver from Lavergne Street. Tug boat crews, meanwhile, sprayed water into the coal barges moored along the river, preventing them from igniting. Finally, and most importantly, the wind shifted direction and blew the flames into depleted areas. The fire burned itself out.

By dawn, ten blocks were charred utterly, leaving “a forest of chimneys” amid lingering smoke and glowing embers. At least 193 houses were destroyed and dozens more damaged, not to mention commercial assets along the riverfront and infrastructure all around. Roughly 1,200 people found themselves homeless, and while no one was killed, a few suffered minor burns and smoke inhalation. Losses were estimated at $400,000, or $11.4 million in today’s dollars. There was no Red Cross nor FEMA at the time, nor any government disaster-relief programs to mitigate the losses for those who did not have fire insurance.

How did the fire start? Raising suspicions among neighbors was the rumor that Paul Bouffia, the occupant of 307 Morgan, had recently acquired insurance. Bouffia was not a popular man; the Picayune cited a source describing him as “heartily disliked,” with “a very bad reputation,” particularly among his own people, one of whom he had “nearly killed.” Neighbors spoke of his suspicious behavior the day prior, and reports circulated “that he had [started] two fires in the place before, which narrowly escaped being disastrous.”

Police located Bouffia and carted him to a provisional police station. Enraged survivors gathered outside, “and some were bold enough to openly cry out to lynch him.” Others, according to Seymour, spoke of “a contemplated expulsion of the Italian element of the population.” Only four years earlier, in 1891, eleven Italians accused of murdering the city’s police chief had been cornered and shot by a mob at the Orleans Parish Prison, precipitating a diplomatic crisis between the US and Italy. Bouffia might have met the same fate had not the police safeguarded him until the mob dispersed.

Meanwhile, a mob of a different sort gathered on the ferry, this one of curious gawkers from across the river. So many spectators mounted the iron bridge to the Algiers Ferry House that the gangway collapsed, sending a hundred people into the water. Twenty were injured, two girls disappeared into the current, and a woman was later found drowned.

The initial response of some New Orleanians to the disaster was, in sum, far more disastrous that the fire itself, and both the lynch mob and ferry collapse gave the city some highly unflattering national news coverage.

What got less national coverage was the charitable response of many more New Orleanians. Leaders and citizens alike formed a Relief Committee that same Sunday afternoon and secured food and shelter for victims at churches, meeting halls and schools (though all were racially segregated). In the ensuing weeks, nearly $16,000 in donations was raised, or $457,000 in today’s dollars — enough, along with insurance claims ($300,000, or $8.5 million today) and social support networks, to get victims at least back on their feet if not whole again. The episode serves as a reminder that disaster response in this era was largely funded and coordinated by civil society and religious institutions.

The neighborhood recovered speedily, as the fire had occurred during prosperous times and in the midst of promethean Progressive Era infrastructure improvements. Streets were paved; electrification arrived; a waterworks plant was built to resolve pressure problems; a viaduct was installed to decongest riverfront activity; and a new Moorish-style courthouse with asymmetrical crenelated towers was built, a distinctive landmark to this day.

New Victorian townhouses and exuberant gingerbread shotgun houses were erected in such numbers that, by late 1896 according to Seymour, “a walk along those attractive streets make it difficult to realize that this was the same so lately in ashes and ruins.” A similar stroll today is a living lesson in 1896-style urbanism, and it is quite beautiful. One might be tempted to say that if Algiers had to burn, it did so at a good time.

As for Paul Bouffia, the target of the lynch mob’s vengeance, overwhelming evidence arose at a November court hearing that he was on the East Bank when the fire started, and that the accusations against him derived entirely from personal animus. “Opinion in Algiers has changed altogether in favor of the suspected man,” reported an out-ofstate newspaper, and Bouffia was set free.

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture is the author of “Bourbon Street: A History,” “Bienville’s Dilemma,” “Geographies of New Orleans” and other books. He may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, or @nolacampanella on Twitter.