In yet another chapter in the ongoing saga of the Hard Rock Hotel collapse at Rampart and Canal streets in New Orleans, the city may lose historic buildings when the compromised hotel is demolished. The unfinished Hard Rock building collapsed during construction on Oct. 12, 2019, claiming three lives, injuring several others and disrupting many more, including nearby businesses. Precise demolition plans were not public as of early December, when the owners filed for permission to demolish three additional, adjacent structures. Their permit requests read: “Existing structure is located in the ‘Red Zone’ … Demolition of this structure is necessary to facilitate demolition operations and planning required at the 1031 Canal St. site.”

The three existing buildings are 1022 Iberville, 1019-25 Canal and 1027 Canal; the two fronting Canal are the most historically significant. Their facades were altered in the 20th century, but due to safety concerns, investigators with the Historic District Landmarks Commission have not been admitted to assess the condition or the extent of the historic elements remaining in each structure. Each building contributed in some way to the evolution of music and film in New Orleans.

Aerial image courtesy of Oldentimes Productions

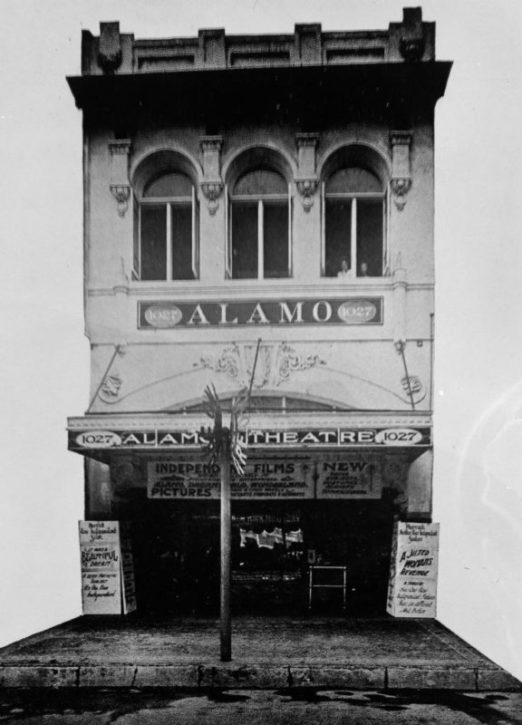

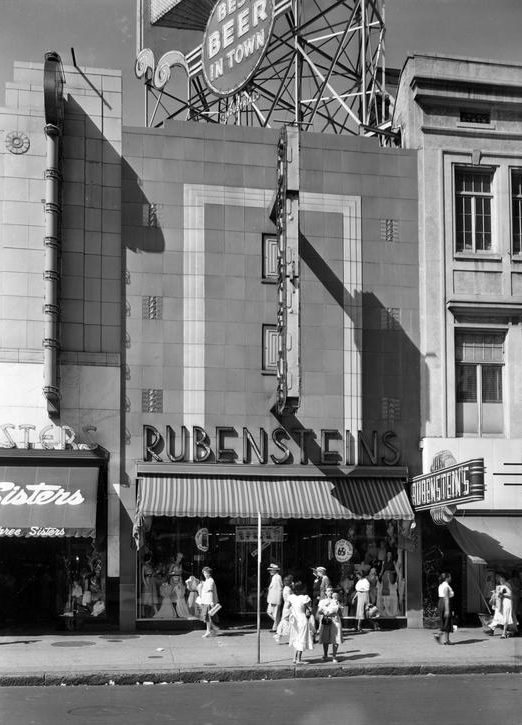

Located at 1027 Canal, immediately adjacent to the Hard Rock Hotel, the former Alamo Theater opened its doors in 1908. According to a Times-Picayune article about the theater’s debut, “the pictures yesterday were: ‘The Ranchman’s Love,’ a beautiful and touching story of the West, and ‘A Voice from the Dead,’ a labor story of the workman intermingled with a vein of love.” Designed by Emile Weil, who also designed the Saenger Theatre, and owned by Herman Fitchtenburg, the Alamo featured live music to accompany silent films. Performers included drummer Tony Sbarbaro and pianist. J. Russel Robinson, both of whom went on to the Original Dixieland Jazz Band. By 1945, the building had been altered with a metal Art Deco façade and was home to Rubensteins.

Alamo Theater circa 1928 and circa 1945 after its Rubensteins’ facelift, which remains except for the signage. Images courtesy Historic New Orleans Collection.

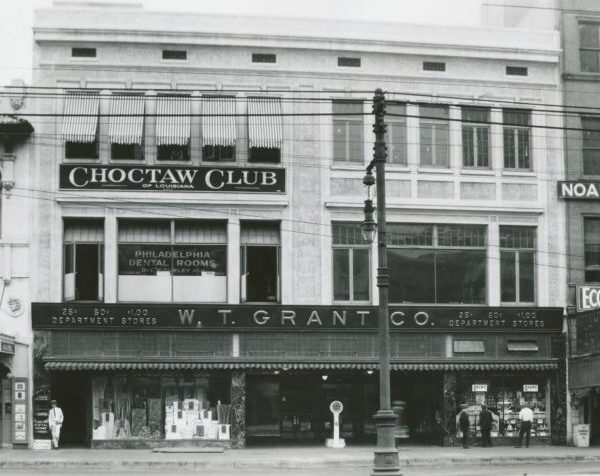

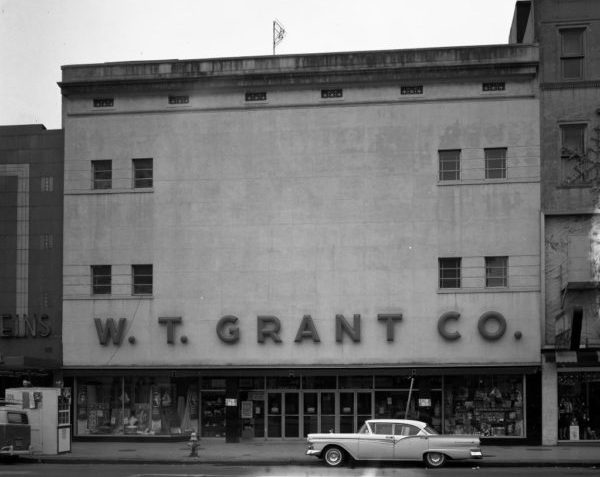

Next door at 1019-25 Canal, the No Name Theater operated during the early 1900s. According to local lore, owner Vic Perez offered a prize for naming the theater but was too parsimonious to make the award. Prior to that time, illustrations show a building of similar size with an Italianate façade when it was home to Dansinger & Son, a retailer of pianos and organs. A circa-1920s photo shows the building as it was rebuilt or remodeled. It was then home to W.T. Grant & Co. department store, with a band of transom windows lighting the shop. Upper floors with casement windows housed a dentist’s office and the Choctaw Club of Louisiana. The club is better known for its now demolished 518 St. Charles Ave. location, which served as informal headquarters for the Regular Democratic Organization, a political machine that dominated city government during the early 20th century. By 1964, the Canal Street building was remodeled in a modernist style, save for the remaining classical attic windows (still visible), and W.T. Grant continued operating from the location.

W.T. Grant & Co. circa 1920 with the Choctaw Club above and circa 1964 with the modern façade still on the building. Images courtesy Historic New Orleans Collection.

According to information from the Orleans Parish Assessor’s Office and Louisiana Secretary of State, the companies that own 1019-25 Canal and 1027 Canal both have Chandra M. Kailas as their sole named officer. Kailas is also the sole named owner of the Hard Rock Hotel. Mayor LaToya Cantrell has stated that the entirety of the structurally compromised, incomplete hotel should come down. If the historic buildings next door are demolished alongside it, one result will be a larger site for future development.

Nathan Lott is PRC’s Advocacy Coordinator & Public Policy Research Director. He can be reached at nlott@prcno.org

Special thanks to Melissa Chua and Hilary Irvin for contributing images and historic research to this story.