This story first appeared in the October issue of the PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door each month? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

For just over a century, a striking Byzantine temple dominated the skyline of the transitional zone between downtown and uptown New Orleans. Its construction marked a significant transformation within a local religious community, while its demolition reflected the uptown residential shift of that population.

The building was the original Temple Sinai, and it stood on Carondelet Street, between Howard Avenue and Calliope Street, from 1872 to 1977.

In many ways, the story of Temple Sinai reflects the geography of the local Jewish community, whose population in the mid-19th century numbered somewhere between 1,000 and 2,000, the largest in the lower South. Those who arrived to Louisiana in the 1700s and early 1800s tended to be of Sephardic tradition, and formed the first local congregations, including Gates of Mercy. Those who arrived later tended to be from Germanic areas, and were generally Ashkenazic.

Enthusiastic participation by recently arrived Ashkenazics in the Gates of Mercy congregation led to the replacement of its Portuguese customs with German ones and the tightening of its mild by-laws with stricter religious interpretations. Discord developed between the two groups, and in the 1840s, the Sephardic faithful broke away to form the Congregation Dispersed of Judah (1846), leaving Gates of Mercy to the Ashkenazics.

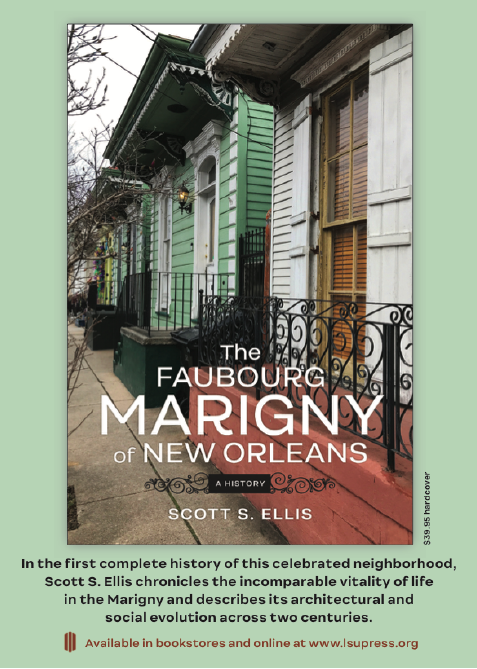

Advertisement

In subsequent years, a Reformist movement among German Jews starting gaining traction in America, including in the Jewish community in New Orleans. In 1870, James Koppel Gutheim, previously the leader of Gates of Mercy, founded the city’s first Reform congregation, Temple Sinai, consisting of many Gates of Mercy members.

With the “cultivation and spread of enlightened religious sentiment” as its mission, the congregation in 1871 bought a lot from the Grand Lodge of the Masons of Louisiana at what is now 1032 Carondelet St. On November 19 of that year, the congregation held a cornerstone-laying ceremony for a magnificent new temple, among the first Reform synagogues of its size in the country.

Designed by local German-American architect Charles Lewis Hillger and built by Peter R. Middlemiss, Temple Sinai cost $104,000, seated 1,500 people, boasted a $6,000 organ and used a thousand gas jets for illumination. Its twin 115-foot-high towers of the Roman-Byzantine order, not to mention its striped coloration of red and yellow bricks and a steep 20-step granite entrance staircase, made it a striking visage from both afar and near.

Temple Sinai stood on Carondelet Street near the corner of Calliope Street from 1872 to 1977. This photo was taken in the early 1900s. Note the dome of the New Orleans Public Library in the background. Photo courtesy of the The Historic New Orleans Collection.

When it was completed in 1872, Temple Sinai was the most prominent Jewish landmark the largely Catholic city had ever known. “The position of the Temple Sinai is extremely well calculated to give effect to its magnificence and well-proportioned dimensions,” wrote the authors of the 1885 Historical Sketch Book and Guide to New Orleans and Environs. “The eye can rest upon the gently acclivity of the broad and elegant building, with marble steps leading to a wide and beautifully arched portico…. On each side of the entrance rises an octagonal tower [with] eight windows, and countless lesser eyelets…fringed with all the circles, curves and scallops of Byzantine and Gothic architecture, and capped by mosque-like green minarets.”

This was the era when Eastern European Orthodox Jews began to arrive at New Orleans, as they also did in much larger numbers to New York. More traditional in their observation of Judaic law and culturally and linguistically isolated from the wealthier resident Reform population, Orthodox Jews settled separately, establishing businesses at the Dryades Market and along Dryades Street, and residing in the part of today’s Central City between what is now Oretha Castle Haley Boulevard and St. Charles Avenue.

By 1890, roughly 550 Orthodox Jewish people worshipped in seven small congregations with a total property value of $20,000, whereas 2,200 Reformists worshipped in two large congregations — Temple Sinai and Touro Synagogue — valued 10 times as much, at $215,000.

The upward mobility of the Reformists led them to do what other well-off New Orleanians were doing at this time: move out of the gritty urban core and into attractive new uptown residential neighborhoods.

Advertisement

It should be noted that New Orleanians in this era had different notions of “downtown” and “uptown;” unlike today, the Lee Circle area, including Temple Sinai, was generally deemed to be uptown, even as the city expanded farther upriver, to the leafy residential areas that we think of as uptown today. As Orthodox families settled around the Dryades Street area, Reformists migrated from the “old uptown” of the Temple Sinai area to the “new uptown” farther up St. Charles Avenue.

Their institutions followed. Touro Synagogue — that is, the amalgamated Gates of Mercy of the Dispersed of Judah congregation — moved in 1909 from their antebellum synagogue, also on Carondelet near Julia, to a new home at 4200 St. Charles Ave. Gates of Prayer relocated in 1920 from its antebellum site on Jackson Avenue to 1139 Napoleon Ave.

Two years later, during Temple Sinai’s Jubilee year, the author of a souvenir pamphlet wrote, “The question [of] paramount importance is that of building a modern Temple in an uptown location. It is becoming more and more manifest that our remoteness from the residences, the trouble of stair-climbing, our unmodern heating, lighting and seating, our unattractive and uncomfortable school rooms [and] the lack of modern conveniences generally… are obstructing the congregation, both in its work and in the expansion of its membership.”

The consensus was to sell and relocate. Congregants held their last service in the old temple in 1926, started building a new Byzantine-style synagogue uptown in 1927, and moved to 6227 St. Charles Ave. in 1928, where the congregation remains today.

This aerial scene shows the former Temple Sinai (center) shortly before its demolition in 1977. Photo by NOPSI, courtesy Richard Campanella.

The former Temple Sinai on Carondelet Street, meanwhile, had been sold in 1929 and subsequently fitted with an ungainly front addition covering the cast-iron doorway and marble steps. Commercial uses followed, as an office, storage, a theater and an advertising studio. The landmark was narrowly missed by the right-of-way clearance for the Pontchartrain Expressway to the Mississippi River Bridge (1958), around the same time that the adjacent Roman-style New Orleans Public Library Main Branch was demolished for K&B Plaza. Sydney J. Besthoff of Katz and Besthoff Inc., owner of the famed local K&B pharmacy chain as well as proprietor of the former synagogue, happened to be the great-grandson of one of the congregants who dedicated the building in 1872. Nevertheless, K&B, which had previously run afoul with local urbanists when it had live oaks cut down on the corner of Louisiana and St. Charles, endeavored to demolish the aging temple.

One day in July 1977, preservationists noticed the old temple’s roof being dismantled and began a frantic last-minute effort to save the landmark. By late July, the city had approved the misfiled demolition permit, and, lacking any legal protection, the 105-year-old landmark met the wrecking ball. “The loss of Temple Sinai for a parking lot,” wrote Christine Moe in the October 1977 issue of Preservation Press, predecessor of this magazine, “brings Bestoff…to the top of the list of those who have hurt New Orleans to help themselves.”

Emotions have since cooled, and Besthoff, now 90, is today widely admired for his generous patronage of the arts and civic causes. But upon viewing old photographs of Temple Sinai, it’s hard to view the decision that led to the empty space behind K&B Plaza as anything but a mistake.

Richard Campanella is a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture and the author of “Cityscapes of New Orleans,” “Bourbon Street: A History,” “Bienville’s Dilemma” and other books. He may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, or @nolacampanella on Twitter.

Advertisements