Stroll down Washington Avenue amid Garden District grandeur and you’ll come across, in the 1200 block, a group of homes looking more like those of Lake Vista or Old Metairie and dating nearly a hundred years younger than their neighbors.

They mark the space where once stood one of the most striking architectural displays of wealth from New Orleans’ heady late-antebellum era: the extravagant palazzo and gardens of a debonair and somewhat eccentric magnate by the name of James Robb.

James Robb epitomized that generation of ambitious Anglo-Americans who, as a bemused Pierre Clément de Laussat once put it, “swarm[ed] in from the northern states” in the decades after the Louisiana Purchase, “each one turn[ing] over in his mind a little plan of speculation….” Robb’s origins belied his destiny: born of humble stock in Pennsylvania in 1814 and left to his own devices at age 13, young Robb learned about banking as a clerk in Morgantown on the Monongahela River in present-day West Virginia. That river flowed north to Pittsburgh on the Ohio, which joined the Mississippi and led down to New Orleans, a city routinely predicted in this era to become among the most important and affluent in the hemisphere.

This was the Age of Jackson, and the nation was changing. Americans were moving westward; frontier individualism became a creed; and the genteel aristocracy of the founding fathers increasingly ceded power to the so-called “Jacksonian Man,” that “hardworking ambitious person,” according to historian Richard Hofstadter, “for whom enterprise was a kind of religion.” Everywhere he went, wrote Hofstadter, the Jacksonian Man “found conditions that encouraged him to extend himself.” Chief among such places was New Orleans, where opportunity abounded — for empowered white males, that is. Vast sums of money changed hands, and fortunes were won and lost regularly. It was the sort of time and place that beckoned to smart and savvy characters, and James Robb was as ambitious as any.

Robb arrived at New Orleans in 1837, and over the next two decades, would create a sprawling trans-Atlantic empire that would dazzle a modern-day global capitalist. He opened financial institutions (“The Bank of James Robb”) in cities ranging from San Francisco to Liverpool, and from New York to New Orleans. He formed private utilities to deliver the gas extracted from super-heated coal for municipal lighting and domestic cooking. He partnered with the Queen Mother of Spain to illuminate the streets of Havana, and ventured into transportation, becoming president of the New Orleans, Jackson and Great Northern Railroad Company. Something of a Renaissance Man, Robb was also a patron of the arts and a generous member of civil society; his collection of paintings and sculptures gained national attention, as did his negotiations to exhibit Hiram Powers’ famous sculpture The Greek Slave at a charitable fund-raiser on lower St. Charles Street in 1848-1849. “The irony of its appearance in New Orleans, home to the largest slave market in North America,” wrote local art historian Cybèle T. Gontar, “seems unlikely to have been lost on Robb.” Indeed, it might have signaled the transplanted Northerner’s discomfort with slavery and dismay over the mounting sectional tensions of the day. Nevertheless, Robb also found time to participate in the city’s stridently pro-slavery government, serving in several elected capacities for the Anglo-dominated Second Municipality and for the entire city after New Orleans reconsolidated in 1852.

That was the same year when the Jefferson Parish City of Lafayette (today’s Irish Channel, Garden District and Central City) merged with New Orleans to become the city’s Fourth Municipal District. Robb decided to build a home in the heart of this prosperous suburb. He acquired an entire block abutting Washington Avenue, and aimed to make it the city’s most prestigious address.

Robb wanted more than a home, more than even a city mansion. He wanted a manor with picture-like qualities, complete with statues and landscaping like those in Romanticist paintings of the Italian countryside. That aesthetic had helped launch the “Picturesque Movement” (from pittoresco, “like a painting”) in English gardening, and brought into vogue the ornate buildings of the Italian provinces. Architects began designing Roman- and Tuscan-style villas in the British Isles, then in places like New Jersey, and starting in 1850, in New Orleans, where a “magnificent Italian villa,” as the Daily Picayune put it, had been built on Prytania Street near Jackson for local esquire Duncan Hennen. Costing $22,000, Hennen’s mansion featured a gallery and veranda amid an abundance of marble. Known as “Italianate,” the fancy fashion reflected what architectural historian Joan Caldwell described as “sheer aesthetic enjoyment,” and it appealed to the nouveau riche who, unlike previous generations of elites who favored the staid Greek Revival idiom, had no qualms about showcasing their wealth.

Once again, James Robb fit the bill. In 1852 he commissioned Gallier, Turpin & Company to design an opulent palazzo on a terraced site surrounded by gardens, spanning from Washington to Sixth, and Camp to Chestnut. Neighbors called it “Robb’s Folly,” in part because the landscaping was completed before the edifice, and perhaps because of the ostentatious interior details.

Completed in 1854, the Robb Mansion ranked among the city’s most splendid homes; its style helped popularize Italianate architecture locally, while its park-like setting helped inspire the nickname “Garden District,” which first started circulating in the mid-1850s. “The building,” commented the Daily Picayune in 1856, “two stories high, eighty feet square, [on a] gently elevated terrace…had about it an air of quiet beauty, refined taste and substantial comfort…. No expense was spared on finishing[;] its fresco paining was particularly superb, [as are the] marble steps, with massive railings, [leading] to a spacious hall….”

Alas, Robb would find little happiness on Washington Avenue. The economic crisis of 1857, the death of his wife, and complications regarding her estate forced him to liquidate assets. His art, which the Daily Picayune described as a “large and choice collection of oil paintings, water colors, engravings, bronzes, marble statuary, vases, and other articles of vertu,” was auctioned off the walls, and the entire property was sold to merchant John Burnside for $55,000. Robb eventually departed for Chicago in 1859, sparing him the additional unrest of secession (which he opposed) and the outbreak of Civil War and the occupation of New Orleans (which likely would have derailed his ventures anyway).

Robb dabbled in banking and railroads in the 1860s and even returned to New Orleans for a spell, but never reclaimed his empire. His demise, coupled with the turmoil of the postbellum era, took the shine off his former mansion on Washington Avenue. John Burnside died in 1881, leaving the house empty and its future in question.

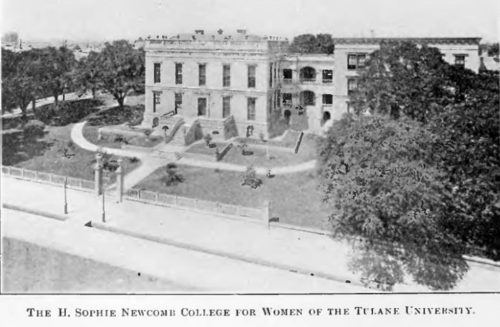

In 1886, local philanthropist Josephine Louise Newcomb set about to establish an institution for higher learning for women dedicated to her late daughter. What resulted was H. Sophie Newcomb Memorial College, the first degree-granting women’s coordinate college in the United States, operating under the auspices of the recently endowed Tulane University. Given the conventions of the day, it was understood that academic facilities for men and women ought to be kept on separate campuses. Whereas Tulane (for men) was outgrowing its Common Street address and would move uptown starting in 1894, Sophie Newcomb College had already outgrown its original home near Lee Circle and, in 1891, found a perfect new campus in the Robb-Burnside Mansion on Washington Avenue.

Administrators had an annex built in 1894, and added another story onto the original house in 1900. A chapel and art department were also built, and in 1902 Ellsworth Woodward collaborated with architect Rathbone de Buys in designing the Newcomb Pottery Building across Camp Street. For years to come, the block bustled with intellectual energy, as hundreds of young ladies earned college degrees in the middle of the Garden District, and Newcomb pottery would become internationally famous. Sophie Newcomb College would become a fixture of uptown society.

By the late 1910s, Newcomb College, its space limited within the confines of a residential neighborhood, found itself unable to accommodate the needs of modern institution of higher learning. Standards by this time had changed, and now men and women were increasingly sharing college campuses. Administrators agreed to move Newcomb College to more spacious grounds adjoining Tulane’s main uptown campus, and sold off the old Washington Avenue property to the Southern Baptist Convention. Seminary classes began on October 1, 1918, only to close the next week for the influenza epidemic. Over the next 35 years, the Baptists saw their student body grow nearly tenfold, for which they added a $200,000 dormitory in 1947. But it soon became apparent that, like Newcomb, the seminary had outgrown its 19th-century home, and in 1953 the Baptists moved to a new campus in Gentilly, where they remain today.

What to do with their Garden District complex? No institutional tenant came to inquire, and the campus could hardly revert to a private residence. “As far the seminary was concerned,” explained a real estate agent interviewed in 1956, “it received more for the vacant ground…than it would have with the buildings on it.” The complex was demolished in 1954; a new segment of Conery Street was laid down the middle of the now-empty block, and the two squares were subdivided into 17 parcels. Roughly $340,000 changed hands ($3 million today) for the land alone, and within a few years, pricey modern houses arose in the core of the historic Garden District.

As for Robb, his fortunes declined amid financial and legal troubles. Some say he died broke and broken, but Robb would have pointedly disagreed. He declared stoically in his last days, “My signature is not outstanding for a penny; the remnant of fortune left is equal to my wants[;] my life one of tranquility, and my daily companions…instruct me in wisdom and impart consolation more precious than riches….” He died in Cincinnati in 1881.

Two clues survive of Robb’s mansion and the college that later occupied it: granite steps at 1230 Washington Ave., which were once the main gated entrance to the compound, and the circa-1902 Newcomb Pottery Building at Camp and Conery, now a residence.

An 1858 photograph of the Robb Mansion by Jay Dearborne Edwards. Photo courtesy of the Southeastern Architectural Archive, Special Collections Division, Tulane University Libraries.

Photos by Richard Campanella