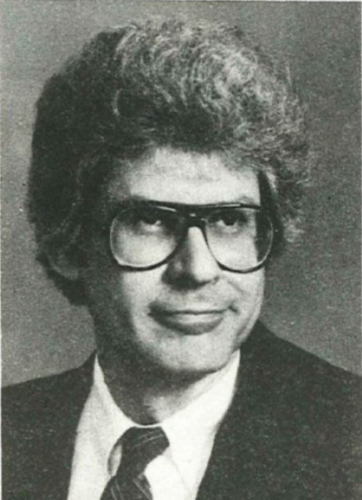

The people who battled for St Charles Avenue 50 years ago didn’t know they would win. One of them was John Geiser III, who died in July at 84 after a life full of preservation causes, many of them successful.

The people who battled for St Charles Avenue 50 years ago didn’t know they would win. One of them was John Geiser III, who died in July at 84 after a life full of preservation causes, many of them successful.

In early 1972, St Charles was in the advanced stages of being ruined. Mansions were coming down, encouraged by a booming economy and zoning laws that made banally large multi-unit apartment buildings profitable.

I was new to New Orleans that spring. I rode the streetcar from Upperline Street to the Lee Circle office of our new weekly “alternative” newspaper, Figaro. Entranced by the city and its architecture, I looked out the streetcar window at the demolitions and wondered why my fellow commuters ignored the cranes and bulldozers that were making flat lots of the wonderful 19th-century houses that made this street one of the most distinctive in America.

That prompted Figaro’s July 12 front page article, titled “St Charles Avenue is Dying.” It showed the dozen or so recent demolitions and related the plans for more. The three-page documentary with photos of vanished and doomed history produced a stronger favorable reaction than I’ve ever gotten for a newspaper article.

The best response was the convening, within days, of a new group, “the St. Charles Action Coalition,” as announced in the next week’s Figaro. It rounded up architects, city planners, lawyers, neighborhood residents and even a Times-Picayune reporter for an organizational meeting July 13, 1972. One quietly prominent convener was John Geiser, who I think lived along St Charles himself.

I can’t recall exactly what role he played then, along with musician Thais Rainwater, but they worked hard and were inspired. They got attention and results. City government under Mayor Moon Landrieu knew that the Poydras Street oil-industry high-rise construction had to be balanced by preservation, and he listened to these animated citizens.

Geiser and his colleagues morphed the group into the still-surviving St. Charles Avenue Association, which he served as president. They successfully lobbied for a moratorium on demolitions along the avenue — a remarkably strong step in a city that then had only one official historic district, the Vieux Carré. The moratorium gave them time to push city and state government for authorization of a Historic District Landmarks Commission in 1975 and the designation in 1976 of the first of a string of New Orleans historic districts to be protected by the commission, first in the Lower Garden District and then along St. Charles between Jackson and Napoleon (with the upper stretch of the avenue added in 2017.)

John Geiser III, who died July 7, was a quiet and effective preservationist. His obituary described someone as busy as possible in saving New Orleans, serving on the first board of the Preservation Resource Center, the strong organization that grew out of the mid-1970s battles to save the historic buildings of St Charles and the Lower Garden District.

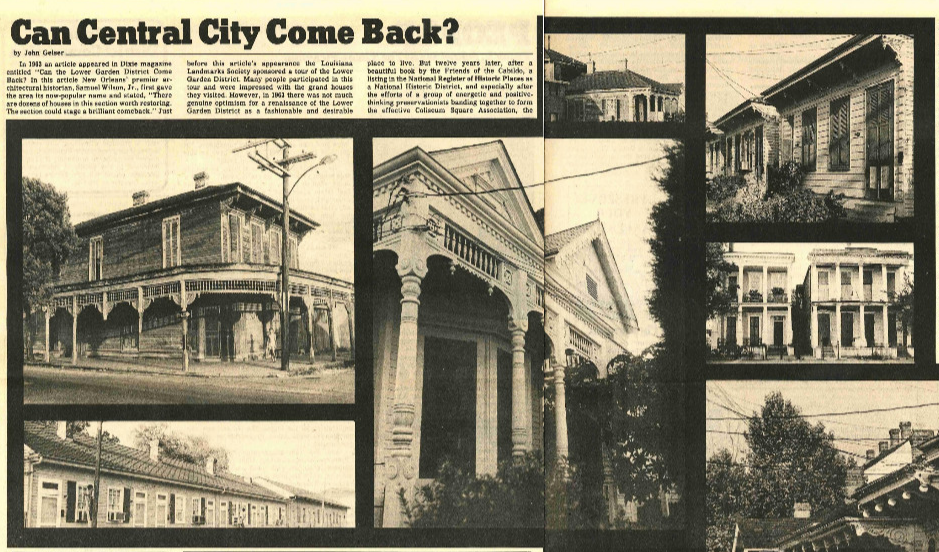

Actively involved with many aspects of the PRC’s work, Geiser wrote articles for Preservation in Print magazine — including a 1975 piece, titled “Can Central City Come Back?” — and he served on the organization’s Façade Servitude Committee.

In addition to the PRC, Geiser served as president of the Louisiana Landmarks Society, Save Our Cemeteries and the Garden District Association. His obituary also acknowledged his service as an officer of the Friends of the Cabildo, the Orleans Parish Landmarks Commission and the organization that runs the Beauregard-Keyes House.

Geiser was not in the headlines much, but he had a remarkable impact. We have a lot to thank him for.