When he was about 10 years old, John Cummings confronted racism in his Mid-City neighborhood head on. His weapon of choice that day was a two-by-four.

“One of my best friends when I was a kid was a black woman named Liz who lived in a double on our block,” Cummings said. “One of the houses there had been on Carrollton Plantation. This woman lived there, and her family had owned it for some time. She was a gardener, and she had a very nice garden.”

On most afternoons after school, Cummings would help Liz work in her garden, and she would leave red-throated daisies in coffee cans on his stoop before leaving for work as a domestic servant.

Photo by Liz Jurey

Another neighbor, a retired police officer named Reinhardt, called Cummings’ mother one day to complain that Cummings was spending too much time with his gardening friend.

Only Reinhardt didn’t refer to Liz by name. He used a racial slur.

“I just marched my little nine or 10-year-old self down there to his house,” Cummings said. “I went up on the porch, and I had a two-by-four leaning against my back so he couldn’t see it. He wouldn’t open the screen door, so I took that two-by-four and I went to hit him. It went right through the screen, and he slammed that door. I guess he called my mother about that, but she didn’t give me a report on the second call.”

In retrospect, it’s easy to pinpoint that decisive reaction to racism as the seed of what would grow into a late-in-life mission to educate the public about the realities of slavery through the internationally renowned Whitney Plantation.

But John Cummings doesn’t see it that way.

“There was no white horse. There was no lightning strike or anything,” he said. “I just got to the point where I couldn’t be a pedestrian anymore.”

A lawyer by trade, Cummings began investing in real estate in and around New Orleans early in his career.

“Whatever Uncle Sam and the bartender let me keep, I’ve put it in real estate,” he said.

Photos by Liz Jurey

In 1999, Cummings decided he should probably purchase a historic plantation along the Mississippi River, mostly because he felt every successful real estate developer in New Orleans should own a plantation.

Cummings says he grew up with what he now sees as a distorted view of life on plantations. The grueling work and often inhumane living conditions of the legions of enslaved men, women, and children who made the elegant life of the gentleman plantation owners possible have been traditionally overlooked.

As well documented as the high society aspect of the pre-Civil War era south’s economy has been, countless enslaved people lived only in the shadows. Their stories, if recorded at all, exist on the periphery of American history.

What started as a real estate transaction quickly evolved into a quest to bring the lives of enslaved people into the bright light of day. And it never would have happened without the cellulose based manufactured fiber Rayon.

The 55-acre plantation Cummings decided to buy, established by German immigrant Ambroise Heidel in 1752 and dubbed the Whitney Plantation after the Civil War, rests on a strip of land about one hour upriver from New Orleans in Wallace, Louisiana.

Heidel originally focused on indigo, but his son switched production to sugar in the early 1800s. In the late 1990s, Formosa Chemical became interested in purchasing the land to build a Rayon plant. Plans for the plant eventually fell through, but it’s fair to say the eight volumes of detailed research into the land’s history conducted by Formosa would eventually change the course of John Cummings’ life.

“I got to the part about successions and how the ownership had been passed down,” he said. “I got to the inventories of the slaves and how they had been categorized. I saw one entry where this female slave was listed as ‘a good breeder.’ She was a ‘good breeder.’”

Cummings turned next to oral histories of slaves who had lived on the grounds of Whitney Plantation and on similar plantations running along both sides of the river.

“I was a grown man, I had degrees, and this was all new to me,” he said. “This had been withheld from all of our educations. It is important for me to make sure that everybody is exposed to the facts of slavery.”

Cummings and his team, who he carefully selected to help him transform the site, embarked on a painstaking restoration of the plantation’s main house as soon as he purchased the land. While the interior portion of the home was more or less intact, the back porch had rotted away, leaving only the columns along the back wall.

“The first thing we did was wrap everything in plastic so it wouldn’t deteriorate anymore,” he said. Great care has gone into the historically accurate restoration of nearly every building on the grounds of the Whitney with the intention of bringing the plantation’s history — including and especially the unpleasant portions — back to life for visitors. In order to tell the complete story, visitors must see the restored beauty of the main house to appreciate the hardship that surrounded it.

Ashley Rogers, the Director of Museum Operations, said the team pored over inventories conducted when the property changed hands to figure out the exact type and style of furnishings to use to restock the house.

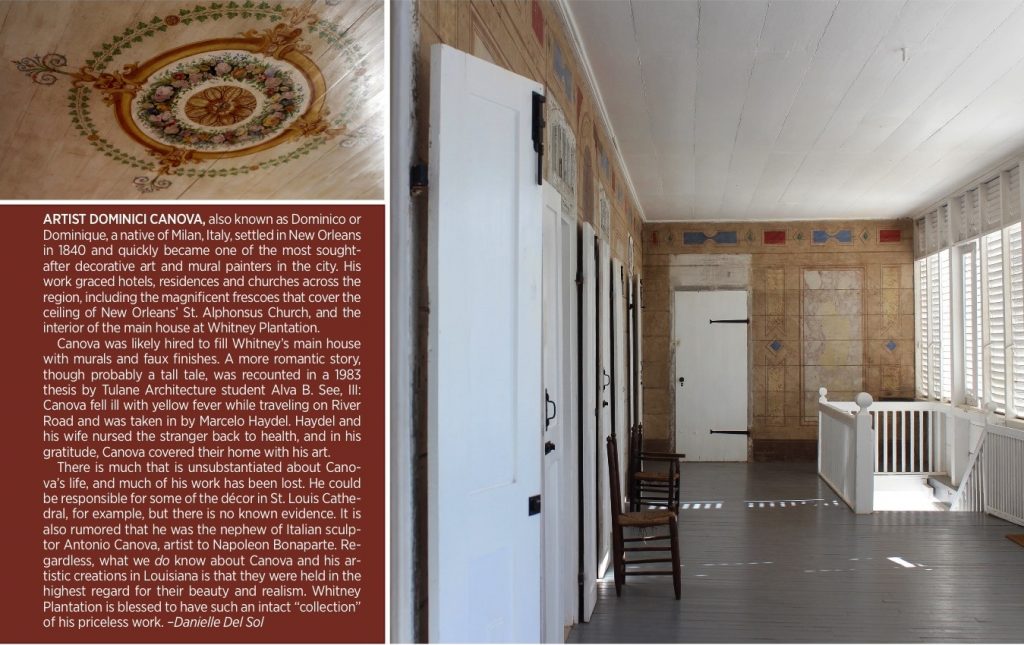

The bigger challenge, though, proved to be restoring the hand-painted faux marble finishes that adorn nearly every baseboard, door frame and piece of trim. Restoring the murals, each with a theme to match a specific room, also proved daunting.

“The painter was named Dominici Canova. He did some work in the Cabildo and San Francisco plantation,” Rogers said. “By the 1840s, the owners were coming out of a recession, they were making a lot of money, and they just covered everything with faux marble. We just sort of conserved it as is, which gives it a lovely rustic look.”

Photo by Liz Jurey

A pair of pigeonniers flank the main house at the entrance along the river, while a large cistern marks the rear. On one side of the house, a historic French barn with massive, Norman trusses still stands.

Yet as beautiful as it is, the main house is not the main attraction.

In fact, visitors don’t even see the main house until the very end of the tour, when they enter through the back door.

The first stop on the tour is a very different historic building: the Antioch Baptist Church.

Founded just after the Civil War by a group of freedmen, the historic church was originally called the “Anti-Yoke Baptist Church” to drive home the image of the newly free slaves shedding the oppressive yoke of slavery.

The church was originally located on the other side of the Mississippi River from the Whitney Plantation. After the congregation, which is still active today, moved to a bigger church about 15 years ago, the historical building was divided into three sections and hauled across the nearby Veterans Memorial Bridge before undergoing a painstaking restoration.

Rogers said many of the approximately 34,000 visitors who toured the Whitney in its first year of operation have deep connections to the church.

“There are a lot of community members that have very fond feelings about this church,” she said. “I’ve had a tour guide who was baptized in this church. I’ve had people come on tours who were married in this church.”

Those enduring connections to a physical historic building allow visitors to connect to the story of the people enslaved on the plantation’s grounds in a very real and visceral way.

Of course, the waist-high sculptures of enslaved children scattered throughout the church also help. They serve to humanize the now-distant past while drawing into sharp focus a representation of the daily lives of the plantation’s past inhabitants.

Photo by Liz Jurey

The statues, created by Ohio-based artist Woodrow Nash, depict children, enslaved from birth, in various poses. Some line a pew along the church’s back wall near the main entrance, seemingly restive during a long service. Others slouch in small groups, clad in worn handspun clothing, appearing at once impossibly young and worn out by life.

One stands, eye-level to anyone seated in the first pew, imploring face craned forward, challenging anyone on the tour to ignore the reality and the myriad implications of child slaves.

The effect can be too much to bear, and it’s only the first stop of the walking tour.

“People have different reactions to different things, and some people are really affected right away,” Rogers said. “You usually see this kind of ‘wow’ effect take over when people go to the Gwendolyn Midlo Hall walkway. The memorial has the names of 107,000 people who were enslaved in Louisiana. I think when people see the scale and see all of those names, it really hits home.”

Cummings said one visitor excused himself as the rest of his tour group walked along the expansive memorial to vomit in the grass.

“He just didn’t know what to do,” Cummings said. “He had to grieve.”

Dr. Ibrahima Seck, Director of Research for the Whitney and a native of Senegal, where approximately 60 percent of Louisiana slaves were born, sees much more than names inscribed on the black granite walls of the memorial.

He sees representations of complete lives. He sees people who ate, slept, wept, laughed, cried, prayed, and tried to retain a sense of humanity within a culture structured around the commoditization of anyone born in Africa or born to African parents.

“One of the things that this wall shows you is how people did hold onto their African names, although they were baptized,” Seck said. “We see the name of a guy from Senegal who was baptized Abdul, which was his African name. He was from a Muslim society, and his name remained Abdul until he died here on this plantation on November 7, 1839.”

Other enslaved Africans died with names like Stephen, Suzanne and Toussaint. Some retained their native religions, which many slave owners demonized as Voodoo. Others, mostly from the Kingdom of Kongo in what is now northern Angola, were Catholic at the time of their enslavement — Kongo had been converted in 1491.

Such fascinating tidbits of historical fact tend to be churned to the surface any time scholars focus on civilizations of the past. The unsettling underlying truth of slavery in America is that, until very recently, the majority of Americans not descended from slaves mostly simply did not know the facts of the recent past.

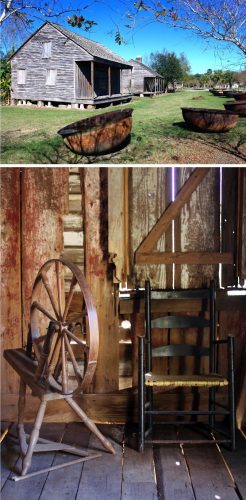

There were 22 slave cabins on the grounds of Whitney Plantation before the Civil War. In those cabins, which were razed in the 1970s, as many as 150 to 200 slaves resided at any one time, according to Ashley Rogers, although that number fluctuated constantly in response to any number of economic stimuli.

Photo by Liz Jurey

Bare-bones examples of raised wooden Creole Cottages, the double cabins offered few amenities. The central chimneys would have housed cooking fires and kept the inhabitants warm, while the sparse rooms would have served as not much more than places to sleep.

No records exist describing exactly how many people lived in each cabin, Rogers said, and details such as what type of bedding was used have been lost to time.

The slave cabins that stand now on the grounds of the Whitney were transplanted from nearby plantations. The historic structures do not serve as specific historical markers, but rather act as a curated exhibit to evoke a sense of the daily lives of the people who were enslaved on the plantation.

While the lives of plantation owners and their families are often documented down to the names of people who paid social visits on specific days, that just isn’t true with slaves. The Whitney strives to present a glimpse of what daily life would have really been like for slaves living on the plantation between about 1820 through 1870, Rogers said.

“I think there’s always concern within the preservation community any time that you bring in historic buildings from elsewhere that you’re going to turn it into a ‘history zoo,’” she said. “I don’t really see that as what we’re doing here. It all adheres to one central narrative, which is the narrative of slavery in Louisiana.”

Along the way, the narrative reveals details of the lives of many people who lived and died on the grounds. People like a slave named Victor Theophile Haydel.

Victor Haydel’s mother was an enslaved woman named Anna, and his father was Antoine Haydel, a direct descendent of the plantation’s founder, the family’s last name having been anglicized from the original “Heidel” to “Haydel” through the generations. Though his father was a Haydel, his mother was a slave, so Victor was a slave as well.

And yet from that suffering rose greatness: Victor Haydel was the great-grandfather of prominent civil rights activist and educator Sybil Morial, who became First Lady of New Orleans when her husband Ernst N. Morial was elected as the city’s first-ever African-American mayor. Their son, Marc Morial, also served two terms as Mayor of New Orleans, and is currently the president of the National Urban League.

For John Cummings, the only way to deal with slavery is to educate the general public about the realities of it, which he has done by inverting the typical plantation-visit experience.

“We have to use this to educate people so that they will understand what the facts of slavery were,” he said. “We know that you can’t rewrite history, but you can right some of the wrongs of history. The way you do it is through education.”

Likening the changes in contemporary race relations to a battleship having its course changed by degree, Cummings said education is the tiny rudder making that big ship turn.

“All we need is passionate people who understand history,” he said. “They have to understand history. That’s the future.”

Photo by Liz Jurey