This story appeared in the April issue of the PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door monthly? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

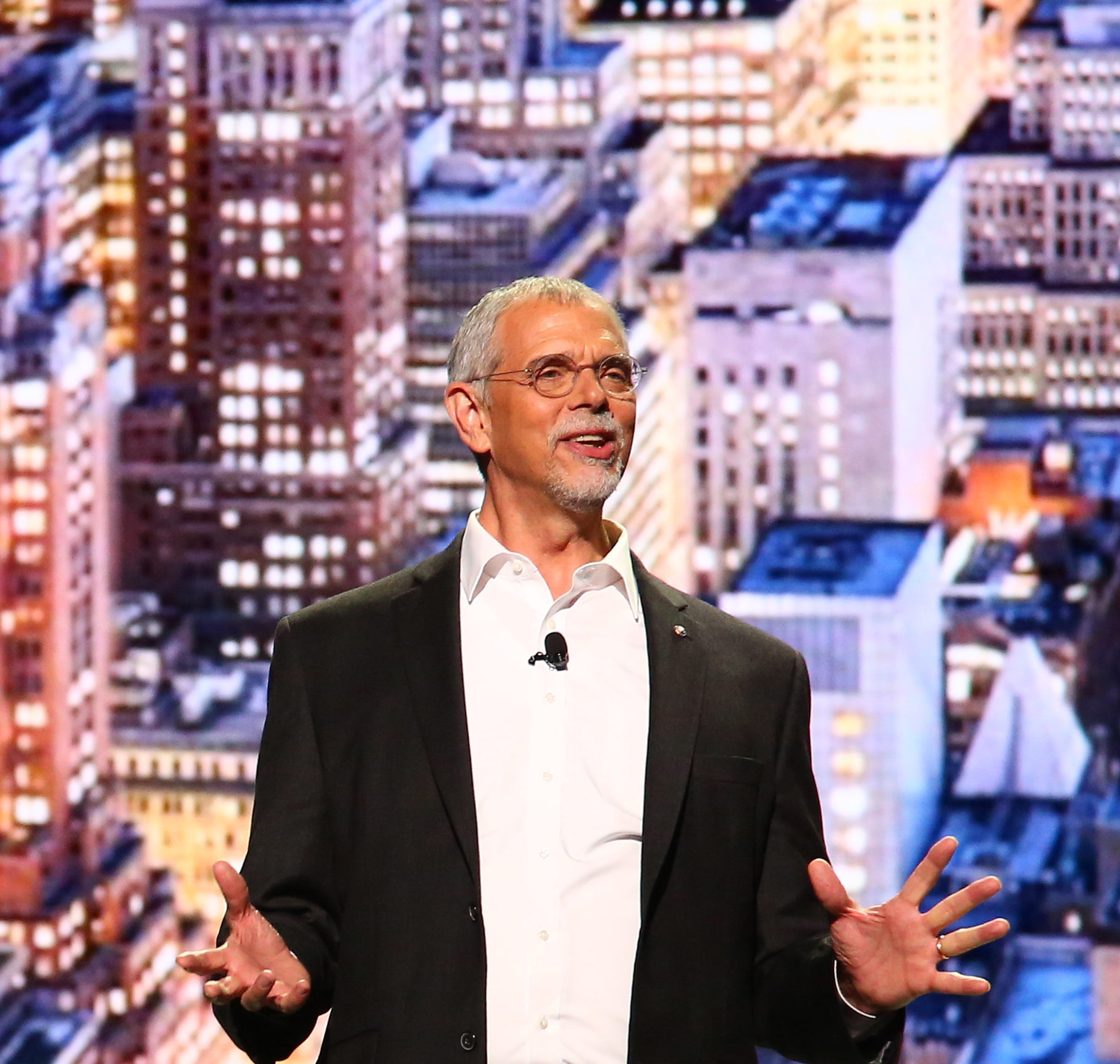

Architect Carl Elefante coined the brilliant phrase: “The greenest building is one that is already built.” Throughout his career, he has championed the concept of sustainable stewardship, and he brought that idea to the forefront when he served as president of the American Institute of Architects’ national board in 2018. At the Association for Preservation Technology Conference in Miami last fall, Nathan Lott, PRC’s policy research director and advocacy coordinator, met Elefante and discovered a mutual interest in sustainable design. For this issue, the two sat down and discussed the ways historic preservation can combat climate change. An edited transcript of their discussion follows.

NL: You served as president of the American Institute of Architects’ national board in 2018. During your tenure you helped elevate climate change to an organizational priority. Tell me how that came together.

CE: To some degree, timing is everything, and there were both the good and bad aspects of that. On the positive side, AIA is pretty thoughtful about paying attention to what’s going on in the world. Things like the adoption of the Paris Agreement (which focused on greenhouse-gas-emissions mitigation, adaptation and finance under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) are obviously very compelling and clearly impact the building sector.

In 2017, the Trump administration signaling their intent to pull out of the Paris Agreement also was a motivator: We can’t just sit here and assume the federal government is going to take care of this. We’ve got to get on it at the professional level and the state and local level. In 2018, there were a few things I was able to encourage the institute to get involved in. I would point to the Global Climate Action Summit (in San Francisco). A group from New England came forward with a proposal to change the AIA code of ethics. Others came forward with interest in some kind of specific climate action proposal for the institute that ultimately led to a resolution adopted at the 2019 convention. I would like to take full credit for all of it, but realistically there were many oars in the water all rowing in the same direction.

NL: What is the role of architects in responding to the threat of climate change?

CE: There’s both a left brain and right brain answer to this. In the first place, let’s just talk about the numbers side of it. The building sector contributes 39 percent of the existing carbon footprint worldwide; 28 percent is the operational carbon. Another 11 percent is what we call the embodied carbon of the building sector. That’s us. It’s what we design. We can’t say we’re not responsible.

The other thing that I think is lost far too often is that we’re envisioners of the future. That’s our job. When a client comes to us and says, ‘I need a three-bedroom house,’ if all you give them back is a three-bedroom house, you consider yourself a failure as an architect. You want to have a house where the views are great, that stays warm in the winter and cool in the summer. We add all these things to it. We leverage that program of the three-bedroom house to create wonderful experiences. Well, I hope that when we decarbonize the world, we will leverage that opportunity to create a beautiful, resilient, equitable, sustainable, regenerative world.

Advertisement

NL: For someone who’s new to the topic, how do you explain that we can reduce the carbon pollution that causes climate change through buildings? What are the key concepts and terms?

CE: Cars pollute. That’s really easy to see: they’ve got a tailpipe. You can see it, you can smell it, you can taste it. You put a gallon of gas in a car, you drive it, it produces carbon pollution that it puts into the atmosphere. Buildings are no different. You operate them, whether they consume fossil fuel on site by a gas boiler or they consume electricity generated by a power plant, both of those are resulting in an operational carbon footprint.

Similarly, picture the car. It’s made of steel, aluminum and plastic. It’s obviously the result of a significant and resource-intense manufacturing process. Well, buildings are too. They are massive assemblies of many systems put together. That’s the embodied carbon: Everything it takes to make a building from extraction of raw materials to manufacture, transportation, construction, even design and commissioning.

NL: So if we need to put the building sector on a carbon diet in order to avoid the worst effects of global climate change, what does that look like?

CE: It’s pretty easy to start with energy efficiency. You make that operational carbon footprint smaller by using more efficient systems. Driving emissions to zero means you’ve got to generate power using clean energy sources, renewable energy sources. On the embodied carbon side, it’s a little different in interesting ways. Not only can you be more energy efficient in how you manufacture materials, but some of those materials can actually be carbon sequestering materials. The classic example of that is building out of wood. Trees through photosynthesis take in carbon dioxide and they make it into wood. For as long as that wood is in your building, you’ve sequestered that carbon. Almost every aspect of the building industry is working on how to create carbon sequestering materials. Concrete is the big one. Concrete is a huge polluter. One figure that I’ve looked at says the number one carbon footprint in the world belongs to China, number two is the U.S., and number three is concrete.

NL: That’s interesting. I’ve always thought there was some basic sense in beginning to put a price on carbon and other pollutants then using the revenue for R&D and retrofits.

CE: If I could wave a magic wand, there would be a very significant avoided carbon tax credit when you reuse an existing building. You would take your real world proposal to renovate the building — we’re going to put storm windows on it, or we’re going to put solar panels on it, or whatever — and come up with the real carbon footprint of your rehab project. Then, you would compare that with the carbon footprint for a new replacement building of comparable size and character. Whatever carbon you’re avoiding by doing your rehab, you get a tax credit.

Advertisement

NL: Being in New Orleans has given me the chance to work with some real thought leaders in the area of climate adaptation and resilience. One thing I found energizing when we met at a convening of the Zero Net Carbon Collaboration for Existing and Historic Buildings is that I felt I now had a vehicle and vocabulary to make an impact on the emissions mitigation side of the climate equation. Do you recall that moment when the lights went on for you?

CE: Very much so. My background is not as a historic preservation architect. I spent a good part of 20 years in a traditional practice. Then I got very interested in green building in the ’80s and ’90s. I got wind of a federal effort to define sustainability in the U.S., then spent about a year and a half volunteering. I came away with my hair on fire about sustainable building and thought, ‘I have to find where this goes.’ I had lunch with (architect) Mike Quinn, who I knew as a friend. He told me about his ethic of historic stewardship. It was like, ‘Wait a minute! Who is bringing these two things together? Who is defining the intersection of environmental sustainability and cultural stewardship?’ Well, nobody was, so we thought, ‘Hell, let’s get busy.’ Within six months, I was working with Mike at his firm, Quinn Evans Architects. I basically have spent my whole career since then bringing these two things together.

When I really look back at what was going on in the world and in New York City when I attended the School of Architecture at Pratt, I see how the seeds were planted. The two things that were going on were the first Earth Day — the whole environmental stewardship movement was happening all around me — and the backlash against the demolition of Penn Station, which was particularly strong at the school. People realized, ‘We can’t let this happen again.’

NL: How does your understanding of our obligation to respond to climate change embolden preservation architects?

CE: I think our perspective as preservationists is super valuable. Why? Because the thing we have to do at the start of every project is to understand the reality of the conditions that we’re facing. For a preservation architect, you have to understand a lot of information in great detail and appreciate existing conditions when you’re starting your project. From that we bring this skill set of being fundamental realists about what’s going on.

The biggest oversight that I’ve come across in the universe of climate action is that this is not about how we design the next generation of buildings only. That’s important. But if we’re going to actually reduce the carbon footprint to zero, we have to address the existing building stock. To the degree it’s recognized, it tends to be: ‘Well, we need to clean up the carbon footprint of the electricity that buildings are using.’ Well, how about reducing the demand because buildings are designed stupidly without energy in mind. … We can learn a lot from the time before buildings became addicted to fossil fuels. Memphis really opened my eyes to that kind of vernacular, climate-appropriate design that you have in the South. The hot, humid climate explains why 19th century buildings had large porches wrapped around them; why those buildings had a central stair with a tower on top of it with operable windows; transoms and things like that. … There’s actually amazingly little appreciation for the kind of system-wide retooling of the built environment that we as architects, and particularly existing building reuse architects — preservation architects — can really bring to this discourse and these solutions.

NL: I sometimes say that preservation is really a tool for achieving social ends. Adding climate action as another social goal to which preservation contributes actually makes the discipline more relevant, but it does challenge us too.

CE: I’ve been engaged for 25 years in bringing sustainability and green building together with preservation and building reuse. That effort has not been one-sided. It has not only been me trying to get sustainability minded people to understand that the greenest building is one that’s already built. It’s every bit as much getting preservationists to realize that their understanding of how to conserve and extend the useful service life of existing buildings has value not just at Mt. Vernon but for every crummy little building. Every building represents an enormous carbon investment and investment by the community. There’s a road outside, there are utilities in that road, there’s a school down the street that has a seat in the classroom waiting for the kid that lives in that house. We have to optimize each one of those resource allocations.

Still curious? Check out these resources for more information on climate resilience, sustainability and historic preservation.

• AIA: aia.org/sustainability

• Architecture 2030: architecture2030.org

• Association for Preservation Technology: oscar-apti.org

• Zero Net Carbon Collaboration: znccollaboration.org

Nathan Lott is PRC’s Advocacy Coordinator & Public Policy Research Director.

Advertisements