Where exactly did a famed frontier photographer capture this image of New Orleans street life?

This article was first published in The Times-Picayune in May 2018, and was republished in the June issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine with permission. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

Serious students of historic New Orleans peruse the limited stock of 19th-century photographs of our city like a family album, and can rattle off building names and dates as if they were cherished elders. I myself enjoy determining the camera’s exact street position all those years ago, so that I may re-photograph the scene as it appears today.

Serious students of historic New Orleans peruse the limited stock of 19th-century photographs of our city like a family album, and can rattle off building names and dates as if they were cherished elders. I myself enjoy determining the camera’s exact street position all those years ago, so that I may re-photograph the scene as it appears today.

Among the long-gone photographers I’ve “stalked” in the streets of New Orleans are Jules Lion, the French-born free man of color who introduced the daguerreotype here in the 1840s; Jay Dearborn Edwards, active in the late 1850s; William D. McPherson and Theodore Lilienthal, who photographed during and after the Civil War; and George François Mugnier, active throughout Louisiana in the 1880s-1900s.

Then there was William Henry Jackson (1843-1942), the famed Western photographer and member of the 1871 Hayden Survey into Yellowstone in the Wyoming Territory. Perhaps best known for his photograph of Colorado’s elusive Mount of the Holy Cross, Jackson’s work brought attention to the natural wonders of the West and helped lead to the designation of Yellowstone as a national park.

Given his treks in the untamed Rockies, it’s hard to picture this frontiersman in the hardscrabble streets of steamy New Orleans. Here he arrived in autumn 1890 (more on this later), and proceeded to capture a number of un-posed and highly informative 5-by-7-inch glass-plate negatives of everyday life: vendors in the Poydras Market, traffic by the French Market and various urban and riverfront scenes.

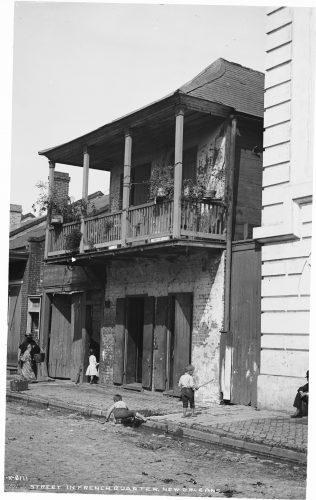

Most locations are readily identifiable, but one has long intrigued and puzzled me: a random moment of children playing in a filthy gutter as a peddler passes and a flâneur rests by a large institutional building. Behind is a time-worn house that could have been in any port city from the Caribbean to the Mediterranean.

What’s striking, in addition to the poetic decrepitude, is the stances of the five neighbors, particularly the peddler, who strides purposefully, attired in wraps and a tignon. Each is in his or her own world, oblivious to the famed photographer and his newfangled equipment in the street. I find myself pondering the worlds of those individuals: perhaps the peddler, who appears to be African American, had been born into slavery; perhaps the children lived to see a man on the moon.

Detail images of a peddler and a young boy from William Henry Jackson’s photo. Courtesy of the Detroit Publishing Company and the Library of Congress

Detail images of a peddler and a young boy from William Henry Jackson’s photo. Courtesy of the Detroit Publishing Company and the Library of Congress

The undated photograph — picturesque yet also melancholic, as poignant as it is quotidian — is captioned “Street in French Quarter, New Orleans,” either by Jackson or by the Detroit Publishing Company, to which he later sold his negatives.

But where exactly? Though the buildings’ styles certainly looked familiar, I did not specifically recognize them. After sharing the scene with my Twitter followers and inviting them to the identification challenge, the mystery only deepened, and I endeavored to solve it like a detective, by amassing clues.

Clue No. 1 entailed the social aspects of the scene. Disheveled walls and herringbone brick sidewalks? Peddlers and poor kids plying stone-paved streets with no asphalt? This was probably not in the more commercial upper French Quarter, which, then and now, had fewer residents, bigger and newer buildings, and more of a business bustle. Rather, this was likely in the lower Quarter, where Creole and Sicilian children had little choice but to play in the streets, and where peddlers sold foods to homemakers door to door.

But the same could be said of adjacent faubourgs, and, realizing that neighborhood names tended to be loose and informal back then, I did not rule out the possibility that this was in the Faubourg Tremé or Faubourg Marigny.

Another clue was the architecture. The main townhouse in the scene exhibits a striking Creole design and perhaps a touch of Spanish Colonial, with its double-pitched hipped roof, wooden balcony with wrought-iron brackets, lack of a centralized entrance, jack-arch lintels above two narrow French doors, a stucco-covered brick façade and clapboard-covered side walls.

Advertisement

All this iterates that the scene is in the lower part of the city, as does the Creole cottage to its left. These sorts of house types and vintages were pretty rare in the upper Quarter by the 1880s

Going a step further, this particular house strikes my eye as dating to the late 1700s, at which time both the Faubourg Marigny and Faubourg Tremé were still undeveloped. This narrowed down my search to exclusively the lower half of the French Quarter.

Next clue: the sun angle. Note the shadow cast by the standing boy and the balcony. Given the orientation of French Quarter blocks, only a south-facing street could yield this sun angle. This qualifies all downriver and lakeside flanks of blocks, and excludes those on the upriver or river side of the street.

Note also the lack of streetcar tracks, which mostly ran parallel to the river. This increases the likelihood that our street ran perpendicular to the river.

Only after obtaining a super-high-resolution version of the photo, and digitally manipulating its pixels, was I able to discern a critical new clue: what appeared to be the number 67 on the wooden frame on an alley.

A house number!

Alas, this could not have been our modern system of addresses, which increments by 100 for every block from Canal Street or the Mississippi River. Introduced in 1894, this so-called decimal system replaced a rather ad-hoc enumeration initiated in 1852 and in place when Jackson arrived.

Advertisement

Quirky as it was, the old system consistently assigned odd numbers to all downriver and lakeside blocks, thus validating our sun-angle and streetcar-track clues: this was definitely the lower side of a lower-Quarter street. And while the 1852 address system was hardly orderly and rational, it was fairly well documented, including by the 1883 Robinson’s Atlas and the 1886 Sanborn Fire Insurance maps, which I consulted next.

Looking for all the 67s in the central or lower Quarter on those maps, I saw some that were structurally inconsistent with our scene. But a few others passed muster, and only one — the lower side of St. Philip Street between Royal and Bourbon — had a large institutional building next to it, a relative rarity in the lower Quarter.

That nailed it.

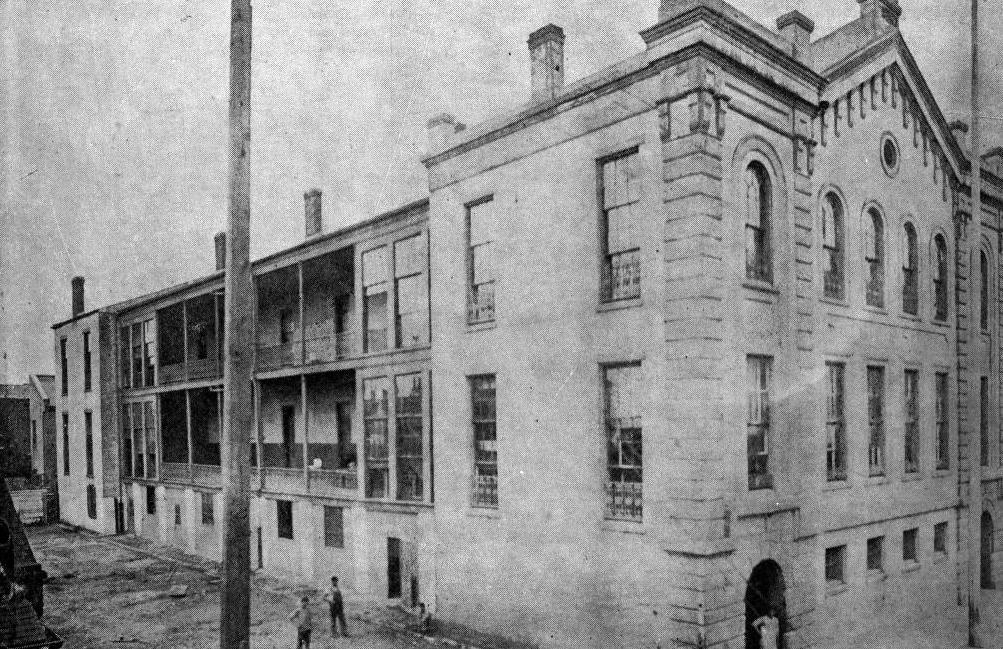

The institution was the St. Philip Boys Public School, built on the site of the famed St. Philip Street Theater, and a precursor to the McDonogh 15 School. A period photo of the St. Philip School shows the same Neoclassical façade partially visible in Jackson’s scene. The insurance maps showed exactly the right juxtaposition of structures and alleys, as well as the correct house numbers.

St. Philip School for Boys. Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection, Vieux Carre Survey.

St. Philip School for Boys. Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection, Vieux Carre Survey.

So, William Henry Jackson, explorer of Western wilderness and pioneer photographer, shot this impoverished port-city scene at what is now 727 St. Philip St.

As to when he snapped the shutter, the Library of Congress says anytime between 1880 and 1897, but it is probably November 1890. This was determined, with the help of @TK_Wharton on Twitter, by finding opera posters which happened to be captured by Jackson’s lens in other scenes during his brief visit, and using searchable online newspaper databases to see when those performances occurred.

Like so many sites in our city, complex and contentious history underlies the seemingly quaint scene. The St. Philip School had previously been the site of racial controversy, when, in the spirit of Reconstruction, attempts to integrate the student body moved forward. The Daily Picayune reported disapprovingly of such efforts citywide in January 1871: “We ascertained that the St. Phillip Boys School on St. Phillip street, between Royal and Bourbon, has been subjected to the same outrage. Five pupils known to be negroes have gained admittance into this school.” They were later refused, and by the time Jackson happened along with his camera in 1890, Reconstruction was over, the segregationists had won, and St. Philip was white only.

As for the old Creole house, its ownership had shifted from families with French surnames (Pottier, Ferran) to those with Sicilian names (Guarino, Vaccaro), reflecting larger demographic changes in this era. Its last owner, Gaspard Noton, sold the property to the City of New Orleans in 1906, which had it torn down by 1908. Its land was eventually acquired by the Orleans Parish School Board; McDonogh 15 was built in 1932 and now sits on three Royal-facing lots and six St. Philip-facing lots, including those of the old theater, the old school and Jackson’s scene.

Today, the peddlers are gone from French Quarter streets (though not the flâneurs), and while hardly any local children still play in Quarter streets, it is a joy to see them in the school yard of the Homer A. Plessy Community School, formerly McDonogh 15.

This last schoolhouse in the French Quarter will give rise to a next generation, and someday, many years hence, we’ll pour over old (digital) photographs of them in the streets of New Orleans and ponder their New Orleans lives.

The site, then and now. Modern photo by Richard Campanella.

The site, then and now. Modern photo by Richard Campanella.

Richard Campanella is a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture and author of The West Bank of Greater New Orleans, Bourbon Street: A History, Bienville’s Dilemma and other books. Campanella may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, or @nolacampanella on Twitter.

Advertisements