This story appeared in the December issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

When the Times Picayune’s former headquarters was demolished in 2019, the dominant concern among preservationists was not the structure itself but the fate of what was inside — specifically, the 150 plaster panels by the sculptor Enrique Alférez that dominated the lobby at 3800 Howard Ave.

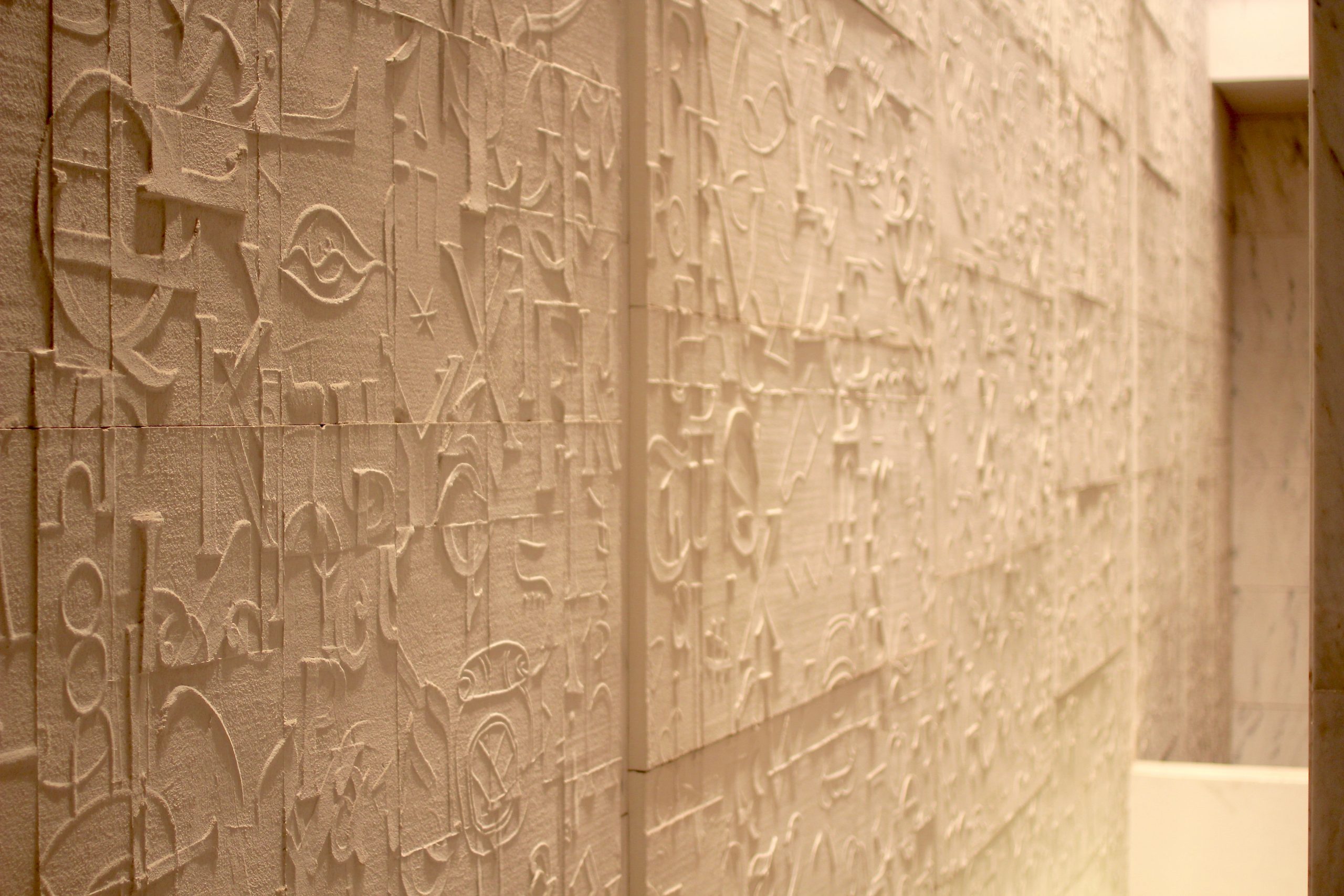

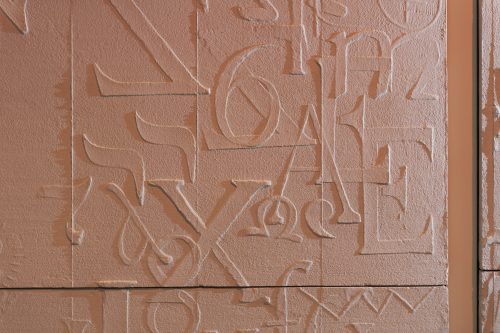

Looming over everyone who stepped inside the modernistic building, the panels ascended 70 feet to the third-story ceiling. They included letters in myriad alphabets and typefaces, as well as Arabic and Chinese characters and even elements of Morse code and Braille. Visitors could get close-up views as they rode escalators to the second and third floors; people with sharp eyes who knew where to look could spot Alférez’s signature amid the jumble of letters.

The fate of the panels, which bear the collective title “Symbols of Communication,” never was in doubt. The partners who had bought the building — Joseph Jaeger, Barry Kern, Arnold Kirschman and Michael White — felt they should stay in New Orleans, even though they had received offers from would-be buyers, including one in Mexico, Alférez’s native country.

“Money is important, but not that important,” Jaeger said in an interview with The Times-Picayune | The New Orleans Advocate. “We’re all New Orleans boys, and we felt … that the best thing to do would be to donate it” to the New Orleans Museum of Art.

At that time, Jaeger was a member of the museum’s board.

The panels have been on view since April in the museum’s Lapis Center for the Arts, which occupies the ground-floor space where the auditorium used to be. Alférez (1901-1999), who spent much of his career in New Orleans creating dozens of pieces of public art, made the panels in a friend’s warehouse in about six months during the mid-1960s.

The panels are now part of the Lapis Center at the New Orleans Museum of Art. Photos by Kyle Encar.

Getting the panels onto the Lapis Center’s walls was tricky, said Christian Rodriguez, the architect in charge of the installation.

Alférez designed each panel to proceed in a sequence from ceiling to floor, with letters from one panel overlapping into the one below. New Orleans Museum of Art Director Susan Taylor likened each sequence to a jigsaw puzzle.

But Alférez designed the pieces for a space 70 feet high. Rodriguez had to figure out how to mount and display them in the Lapis Center, where the ceiling is only 16 feet high.

“That was the hardest part, for sure,” he told The Times-Picayune | The New Orleans Advocate. “We tried to reproduce (what Alférez created) in a more intimate way.”

To make this happen, Rodriguez and his colleagues had to study drawings and photographs to get the longest continuous runs of panels that hadn’t been cut to make room for beams in The Times-Picayune lobby.

To add to the complexity of the job, each of the 16 sequences chosen for the Lapis Center had a different width.

Mounting the panels mimicked what had been done at The Times-Picayune building, Taylor said. Horizontal steel channels were attached to the wall with short sections of round hollow pipe welded to them, Rodriguez said. Metal channels already had been embedded into the hollowed-out backs of the panels, and copper wire was wrapped around them and pressed into a mound of plaster on and around the short pipes to ensure that the panels stayed put when the plaster dried.

Each panel weighs no more than 100 pounds and is less than 2 inches thick, Rodriguez said.

Advertisement

“The plaster was so thin that they were quite light,” he told the newspaper. “I was super nervous that we were going to break a panel. I thought somebody would drop one or nick one and then someone would have to ask me for something to put in its place. But that didn’t happen. They were able to stack them really tight, with horizontal joints.”

Broadmoor LLC was the contractor for the job, and Intrepid Stone, the subcontractor, installed the panels. The project was underwritten with $4 million from the Zemurray Foundation.

Eighty-five panels are on display in the Lapis Center in 16 sequences. The rest, including the panel bearing Alférez’s signature, are stored in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment, said Anne Baños, the museum’s deputy director.

Showing off the panels to best advantage required lighting that would make the letters and characters stand out. Rodriguez contracted with Huseman Engineering LLC to get what he wanted: lighting that would be more or less evenly distributed along the 16 feet, and at an angle that would produce a shadow — but not one that would be too deep — for each letter or character.

“The letters vacillate between low-relief and high-relief,” Taylor said. “Some forms are less visible, but they’re just as powerful.”

The Lapis Center has been the site for several weddings and, most notably, a dance celebration to mark Juneteenth, the new federal holiday commemorating the emancipation of slaves, said Margaux Krane, the museum’s spokeswoman.

“Because it was a flexible space, we could put down seating around the presentation,” she said. “The way the lighting was used was stunning.”

It was exactly what the philanthropist Edith Stern had in mind a half-century ago, when the neoclassical building underwent its first expansion since its opening in 1911. For that space, Stern wanted a vast, open room with a flat floor that would house a wide variety of events, said E. John Bullard, the museum’s former director.

But, Taylor said, Stern’s fellow trustees overruled her and voted for a conventional auditorium with fixed, raked seating.

This year, the museum unveiled the Lapis Center, with state-of-the-art sound and lighting systems. Because the stage has been eliminated, the Lapis Center, with its flat floor, can accommodate 360 people, 140 more than the auditorium could hold, with a variety of seating combinations.

“Just as Edith wanted,” Bullard said.

Taylor called the Lapis Center “the most logical and appropriate space” for the Alférez panels. This exhibit, she said, “can be here forever.”

Advertisements