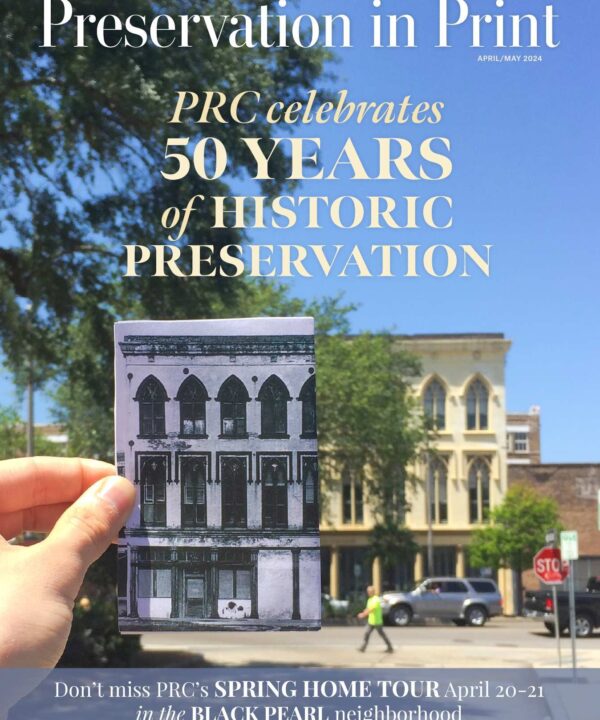

St. Louis Cathedral’s contemporary design, with its mélange of Greek Revival, Gothic and Renaissance motifs, stunned New Orleans in 1849. The heart of a large Catholic community, the cathedral today symbolizes New Orleans’ long cultural ties to Catholicism. Although the city boasts hundreds of fine churches, this building has become the church of New Orleans. But when constructed between 1849 and 1851, the building was a source of controversy and underserved professional disgrace for its designer.

Two earlier cathedrals on site

Mass has been celebrated on this site since 1727, but the story of the current cathedral, designed by French-born architect J.N.B. de Pouilly (1804–1874), begins in the 1830s when the church wardens realized the old Spanish-era cathedral occupying the site was failing. Constructed following the great fire of 1788, which had destroyed an earlier 18th-century church, the second church on the site was the work of Don Gilberto Guillemard, a French engineer in the service of the Spanish king. The stucco-over-brick structure was given a new clock tower in 1819 by America’s first professional architect, Benjamin Latrobe, but less than 20 years later, it was in need of more than cosmetic repairs.

By 1838, funds were being gathered for “the repairing or rebuilding of the Cathedral Church of St. Louis,” and in 1839, a design was approved by de Pouilly, then one of the city’s most successful architects. However, it wasn’t until February 1849 that the drawings, specifications, and agreements with the architect were finalized. The church wardens, perhaps for reason of economy, hoped to merely renovate and lengthen Guillemard’s cathedral. De Pouilly’s final plans, however, show that the old Spanish building would be substantially demolished with only portions of the side and front walls being re-used.

Within months of singing a contract with Irish builder John Patric Kirwan, it became apparent that the lateral walls were inadequate. The situation came to the public’s notice through a piece in the New Orleans Weekly Delta newspaper in June 1849: “The interior of this venerable structure, we perceive, is now entirely demolished by the architect who has undertaken the erection of the new building. … We understand that a portion of the old side walls are to remain and will form part of the new building. This seems to us a great oversight on the part of the architect or the committee who may have the management of the affair in hands. The walls are cracked in several places and seem completely out of line. We trust that the intelligent and public-spirited trustees of the cathedral will, at once, see the propriety of demolishing the portion of the old and dilapidated walls yet standing so that the structure, when completed, instead of being a patch work affair, will be such an edifice as will reflect credit on its projectors and the great city of New Orleans.”

The demolition of the side walls, for which a supplemental $19,000 contract was signed later in the month, enabled the architect to widen the building to its present size. Construction progressed without incident until January 1850 when the central tower, still being erected by Kirwan, suddenly collapsed, taking part of the roof with it and severely damaging the new walls.Subsequent investigations by a panel of experts suggest that the disaster was the fault of the contractor, but de Pouilly was dismissed from the job along with Kirwan. His reputation was tarnished, but his distinctive design was completed as planned.

The new cathedral was blessed in December 1851. (Scroll down to read more. Article continues below image gallery.)

This is a view of St. Louis Cathedral as it appeared in the early 1800s. The painting by Edouard de Montulé from 1820 is courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection, Gift of Mr. Boyd Cruise, Acc. No. 1958.55.

This mid-19th century drawing of St. Louis Cathedral, the Cabildo and the Presbytere by Louis Xavier Magny (lithographer) and Gaston Celestin Delfau Pontalba (draftsman) shows the cathedral with bell-shaped steeples. The drawing dates to between 1845 and 1855. Image courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection, Gift of Mr. Boyd Cruise, Acc. No. 1957.39.

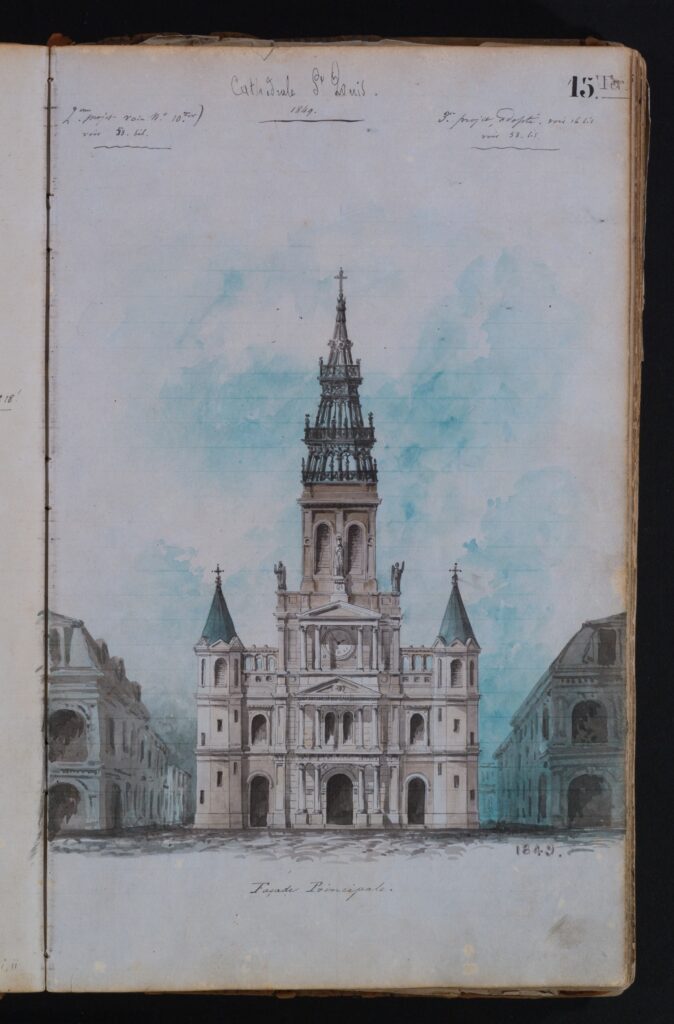

This preliminary design for St. Louis Cathedral from the sketchbook of J.N.B. de Pouilly is marked as the second project presented in 1848. The building resembles the famous Notre Dame in Paris. Image courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection, Acc. No. 1979.93.

Although changes were made before the cathedral was completed, this design from dePouilly’s sketchbook is marked by the architect as the project which was adopted in 1849. The openwork iron spire, which resembles the spires of Parisian Gothic churches, was slated over in 1859. Image courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection, Acc. No. 1979.93.

Avant-garde design

Although it was generally acclaimed, there were detractors, one of whom commented, “When the old structure was torn down, many of the ancient regime of New Orleans wept.” Another called the exterior “garish” and “showy,” complaining that it “fails to impress the beholder with that reverential awe for sacred objects, which constituted such an important feature in the Old Cathedral.”Such criticism might have been directed at any new cathedral replacing the “venerable relic” of the colonial past, but perhaps the striking modernity of the design contributed to the dissatisfaction.

Although it is difficult for us to imagine today, St. Louis Cathedral was avant-garde in its day. It embodied one of the latest concepts in French Romantic design — the idea of combining elements from several historical styles in one structure. As architects during the 1830s and 1840s began to explore a wide variety of historical periods, the Greek and the Gothic came to be regarded as twin examples of design creativity and freedom. Although totally different in appearance, the two styles were thought to be related in spirit by their common originality. Modern French design theorists embraced the idea of combining elements of each in imaginative and original buildings.

This fusion of the two styles is what de Pouilly achieved in his design. Rather than electing to build in the Greek Revival style, as had James Gallier Sr. at Gallier Hall (1845) or in the Gothic Revival, an example of which is the Leeds warehouse (1849), de Pouilly chose the more modern path of utilizing elements from both styles. His combination is so successful that no particular design source dominates the composition.

While the spires and towers are Gothic references, the central section recalls Renaissance church facades, and the framework of arches, pilasters and ornament is derived from Classical architecture. De Pouilly was creating a new and modern way by combining historical motifs into a whole that is an expression of his own imagination rather than imitation of past styles.

Perhaps inspired by Notre Dame

De Pouilly’s final design was preceded by several compositions that may have helped him arrive at his unique solution. One preliminary sketch is for a Gothic-style edifice resembling the famous Notre Dame in Paris. Another incorporates a Classical-style portico and copious statuary. In the 1849 design that was adopted, de Pouilly brings life to the remark of an esteemed Parisian designer who said, “While a modern building must be a mélange, it must also be a homogenous whole.”

One feature of the 1849 drawing is a distinctive central spire composed of a decorative, open, wood and wrought-iron framework. Unfortunately, this unusual element was slated over early in the building’s history. In spite of the increasing use of architectural iron by 1850, its popularity alone does not account for this unique feature. In seeking de Pouilly’s inspiration, one is drawn to the writings of Victor Hugo. While it is little known today, the famous 19th-century French author was intimately involved in the intellectual and architectural criticism circles of his day. His notable work of fiction, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, was an indictment of the Renaissance, which he characterized as a period of “magnificent decadence.” Hugo encouraged the appreciation of Gothic buildings through this popular novel, which was almost surely known to de Pouilly.

Hugo especially admired the long-disappeared spires of Notre Dame, calling them “perforated, sharp, sonorous, airy,” a description perfectly suiting the spire created by de Pouilly, who was perhaps inspired by Hugo’s picturesque and romantic description of a lost architectural treasure.

A lasting design

Today, not only parishioners, but also locals and visitors from around the world, appreciate St. Louis Cathedral for its spiritual, historical and aesthetic qualities. It is only fitting that all who cherish our past should contribute to its longevity.