This story appeared in the November issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

Calle de Almazen. With those words, New Orleans city surveyor Carlos Trudeau created what would later become Magazine Street, specifically its first five blocks. The date was April 24, 1788, just over a month since the Good Friday Fire — a disaster so thoroughly destructive of New Orleans proper that it spurred the Gravier family to subdivide their adjacent plantation to abet the process of rebuilding.

Trudeau devised a street plan for the Graviers’ new faubourg, which would be called the Suburbio de Santa Maria in Spanish and the Faubourg Ste. Marie in French. He happened to position one particular calle a block in from El Camino Real (Royal Road, today’s Tchoupitoulas Street) and named it almazen (warehouse), probably because it started near a bastion and fortification by what is now the U.S. Customhouse, which had a tobacco warehouse on the outside and a magasin (powder magazine) on the inside. Being a mostly Francophone city despite Spanish governance, locals tended to refer to the new rue by its association with the magasin rather than the warehouse. Calle de Almazen appears on maps through the late 1790s; Rue des Magasins or variations thereof start to appear in the early 1800s; and Magazine Street prevails later in the century.

Being the second street from the river turned out to be significant, because as New Orleans later expanded, this juxtaposition would make Magazine too far from the river to be predominantly commercial, but too close to become the mostly residential “grand avenue” that Calle de San Carlos (future St. Charles Avenue) would be. In time, Magazine would attain the best of both worlds, an interleaving of commercial and residential land uses like no other street in the city.

Advertisement

Whereas Carlos Trudeau created Magazine Street, it took another surveyor/engineer to steer Magazine toward its future destiny. Multi-talented and incredibly productive in the engineering of New Orleans at the turn of the 19th century, French-born Barthélemy Lafon was commissioned in 1806 by Madame Silvestre Delord-Sarpy to subdivide her plantation immediately upriver from the Faubourg Ste. Marie, roughly at Howard Avenue. Delord-Sarpy soon sold her land to Armand Duplantier, who appears to have consulted with his three upriver neighbors — the Saulet (Solet), Robin and Livaudais families — all of whom agreed to have their plantations turned over to Lafon to include in his subdivision for urbanization, up to Felicity Street.

For this expansive terrain, Lafon devised an elaborate plan, part Classical and part Baroque, which aimed to extend Trudeau’s Ste. Marie street grid upriver, while at the same time “hinging” it open to create new streets upon the broader natural levee. (Think of how Annunciation Street forks off from Tchoupitoulas, and Prytania Street splits off from Camp Street: those are some of Lafon’s “hinges.”)

The bifurcations had the effect of repositioning Rue des Magasins, which was originally only one block away from Tchoupitoulas and two blocks from St. Charles, to now being fully six blocks away from both — and with mostly narrow streets in between. Lafon, on the other hand, gave Magazine multiple lanes, slating it for heavier traffic, and because of its now-enhanced intermediary position between the working riverfront and the grand avenue that Lafon envisioned for Cours des Nayades (future St. Charles Avenue), Magazine Street was put on a likely path toward becoming a merchant corridor serving residential neighborhoods.

Today, Magazine Street’s four commercial clusters correspond to old public food market locations. The foot traffic from the markets spurred the development of other retail and service businesses, making Magazine into the street of shops, restaurants and banks.

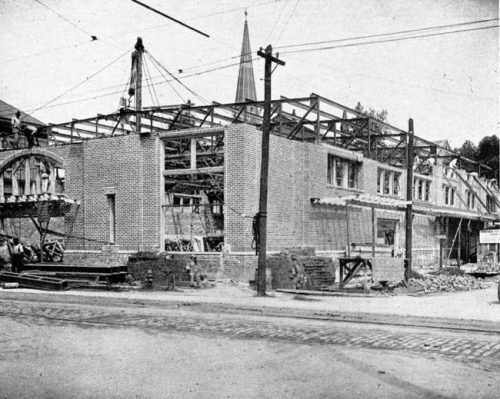

1: Magazine Market, 1911 Magazine St., dates to the 1850s. It was renovated into an indoor space in the 1930s, according to City Business. Photo courtesy of the Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, Acc. No. 1979.325.3977. 2: Now an event space known as Il Mercato, the building was renovated in 2013, restoring many of its historic architectural elements. Photo by Liz Jurey.

Lafon’s faubourgs, named Duplantier, Saulet, Lacourse (former Robin plantation) and Annunciation (former Livaudais plantation), relaunched Trudeau’s downtown version of Magazine onto a new uptown trajectory, through what now we call the Lower Garden District. Most streets were laid out by 1810, and development ensued.

Upriver of Felicity Street, Magazine and all other river-parallel streets got further extended over the course of the 1810s to 1850s, as plantation after plantation became subdivision after subdivision. It was a messy process, initiated by private land owners rather than a city planning agency, and designed by various surveyors who did not necessarily see fit to smoothly extend all streets in shape and name. Those subdivisions closer to New Orleans proper tended to be called faubourgs, whereas those farther upriver got Anglophone suffixes such as -ville, -dale and -burg. The surveying happened out of spatial sequence, such that for many years, any given street might dead-end at a field, until that field too got subdivided. Such are the artifacts of the private decision-making behind most historic neighborhoods in New Orleans outside the French Quarter. Indeed, most of the expansion was not even in the City of New Orleans; it occurred in what would become the cities of Lafayette, Jefferson and Carrollton, each of which would eventually be annexed into New Orleans.

From Felicity, the street extensions proceeded with the subdivision of the Ursuline nuns’ plantation to become Faubourg Nuns (Faubourg des Religieuses), which Lafon himself had laid out in 1810. This brought Magazine Street up to St. Andrew Street. Next came the Panis Plantation, which was subdivided as Faubourg Lafayette by 1818, bringing Magazine Street up to Philip Street. The creation of the Faubourg Livaudais in 1832 extended Magazine up to Harmony Street, and four years later, to Toledano Street, with the 1836 subdivision of Faubourg Delassize.

1: Ninth Street Market, 3138 Magazine St. Photo courtesy of the Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, Acc. No. 1979.325.3981. 2: The building now houses multiple businesses including a jewelry store, an exercise studio, a bakery and an art gallery. Photo by Liz Jurey.

By then, a number of plantation owners farther upriver “jumped the gun” and had their parcel subdivided, even as agriculture continued on plots further downriver. Among them were the former Macarty Plantation, which became Carrollton in 1833; Hurstville and the Faubourg Bouligny in 1834; Bloomingdale and Greenville in 1836, and the Faubourg Plaisance, which had been planned as early as 1807 but commenced in the 1830s. The street grids of these isolated tracts, of course, were not yet aligned with their downriver antecedents, but they were laid out with that likelihood in mind, prompted by the 1833-1835 construction of the New Orleans and Carrollton Railroad, a project which brought a unifying spatial order to future Uptown by making clear exactly where the future St. Charles Avenue would run.

Magazine grew further with the surveying of Faubourg Avart in 1841, Faubourg St. Joseph and Rickerville in 1849, and finally Burtheville in 1854, last of the uptown plantations to urbanize. The only planter family that never quite got around to subdividing their tract was the Foucher clan, and after many convolutions between the 1830s and 1880s, that open land eventually became Audubon Park.

Advertisement

By the 1850s, the Magazine Street artery stretched from Canal Street to the river near Carrollton, as it does today. By 1878 the entire street was called “Magazine” save for the dirt road across the Foucher tract (by now Upper City Park, later called Audubon Park), which was named Foucher Street. By its 100th anniversary in 1888, the name “Magazine Street” graced all 5.3 miles of the street.

Thus, piecemeal urban growth brought Trudeau’s original Magazine Street trajectory all the way uptown, while Lafon’s work positioned Magazine in that “sweet spot” among residential neighborhoods needing convenient commerce. But the same can be said of, say, Prytania Street. Why, then, did Magazine Street become the distinct historic corridor of shops and houses it is today? The answer: municipal markets.

1: Jefferson Market, 4303 Magazine St., was built in 1918 and renovated in 1932. Photo courtesy of The New Orleans Public Library. 2: The building now houses the gymnasium for St. George’s Episcopal School. Photo by Liz Jurey.

Recall that uptown growth happened predominantly upon three separate political jurisdictions: Lafayette (today’s Irish Channel, Garden District and Central City), Jefferson (the heart of modern Uptown) and Carrollton. Each was a municipality with its own standard city services, including a courthouse, police and fire stations, businesses — and markets. Because of Magazine’s multiple lanes and centralized position, it became the street of public food markets — really the only place for the retailing of fresh meat and vegetables.

Because the markets each generated foot traffic and cash flow, they became ideal places to establish other retail and service businesses, making Magazine into the street of shops, restaurants and banks. Because the markets were intentionally dispersed so as not to compete with each other, the commercial clusters formed in a spatially distanced manner, leaving open many blocks to become most residential. And so Magazine also became a street of houses — townhouses, frame houses, mansions, cottages and shotgun houses, with porches and gardens and shaded by live oaks. Because houses meant neighbors, Magazine Street also became home to churches, schools and institutions.

Thus, urbanism at its best: residents, houses, local shops, entrepreneurial opportunities, jobs and neighborhood institutions, all within walking distance. And it all mostly happened rather spontaneously, from the bottom up, without a master planner. New Orleanians made Magazine Street.

1: Ewing Market, 5500 Magazine St., was built in the early 1900s and renovated in 1931. Photo courtesy of the Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, Acc. No. 1979.325.3962. 2: The building now houses Joseph, a clothing boutique. Photo by Liz Jurey.

Next time you go to Magazine Street, note its four commercial clusters. Each corresponds precisely to an old market location — and in all four cases, the historic market structures still stand, at 1911, 3138, 4301 and 5500 Magazine. Originally called the Magazine Street Market, Ninth Street Market, Jefferson Market and Ewing Market, all had closed by the 1950s, and their structures are now used as an event space, two boutiques and a school gymnasium.

But the old public market system lives on through their derivatives — four shopping districts in otherwise residential neighborhoods — and together they trace their Magazine Street historical geography back to the subdivision of the old plantations, to Barthélemy Lafon’s 1806 design and to Carlos Trudeau’s 1788 Calle de Almazen.

Richard Campanella is a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture and author of The West Bank of Greater New Orleans; Cityscapes of New Orleans; Bourbon Street: A History; and Bienville’s Dilemma. Campanella may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, or @nolacampanella on Twitter.

Advertisements