This story appeared in PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

“And by-and-bye we reached the West End, a collection of hotels of the usual light

— Mark Twain, Life on the Mississippi, 1883

summer-resort pattern, with broad verandas all around, and the waves of the wide and blue Lake Pontchartrain lapping the thresholds. We had dinner on a grand veranda over the water — the chief dish the renowned fish called the pompano, delicious as the less criminal forms of sin. Thousands of people come by rail and carriage to West End and to Spanish Fort every evening, and dine, listen to the bands, take strolls in the open air under the electric lights, go sailing on the lake, and entertain themselves in various and sundry other ways.”

West End is home to an unheralded 186-year legacy that ventures from the Olympics to the early notes of jazz, from maritime commerce to a crucial and important leg of the city’s dining and seafood history. Having gone through multiple cycles of boom and bust, West End is on the precipice of another revival following its near complete devastation in Hurricane Katrina, and the languorous reconstruction that followed.

Led by the rebuild and completion of the $27 million Municipal Yacht Harbor Marina in 2021, the area’s unique historical significance and culture should be preserved, incorporated and celebrated as the latest resurgence and re-imagination of West End gains steam.

Maritime commerce birthed West End with the construction of the New Basin Canal between 1832 and 1838. This feat of engineering dug by thousands of Irish immigrants was meant to facilitate the lake trades of seafood, goods, mail and lumber hauled by schooners navigating the shallower inshore and near-shore waters of the northern Gulf Coast.

The New Basin Canal Lighthouse was completed in 1838, and West End began developing with rustic camps, rowing and shooting clubs and boat chandleries, which were followed by music clubs, boutique hotels, raw bars and seafood restaurants, including the legendary Bruning’s, which opened in 1859. In adjacent Jefferson Parish, Bucktown was a ramshackle fishing village that would populate with a gritty assortment of gambling dens and houses of ill repute, while West End grew to feature grand hotels, expansive greenspaces, pavilions and bandstands with a certain posh air.

At its heart, the success of West End was always connected to the maritime trade. With the port on the Mississippi River accommodating larger ocean-going ships and river barges, the lake trade served the northern Gulf Coast from Galveston to Pensacola, and the New Basin Canal fed these vessels into the turning basin adjacent to Storyville.

Following the Civil War, many of these smaller, shallow-draft schooners carrying goods, seafood and lumber were helmed by newly freed Black men who learned their trade crewing boats while enslaved. These boat captains and their crews formed a burgeoning post-war, Black middle class in the city.

As a resort, West End had a more relaxed and forgiving racial tolerance than many neighborhoods of the city, especially in the late 1800s. Over-the-water music clubs and restaurants dared to feature diverse bands, and after hours, musicians of all races would drink and improvise together on the piers. The

Times-Picayune Guidebook of 1896 referred to West End as “the Coney Island of New Orleans,” noting its “number of hotels and restaurants and all sorts of devices for public amusement.”

“On an immense platform, built on piles over the water of the lake, is a music stand, where a fine band discourses music every evening during the summer to all who care to listen,” the guidebook said. “The open air concerts are extremely popular, thousands of people resorting hither nightly to enjoy the music and the cool breezes from the lake.”

With boats often docked along West End and the length of the New Basin Canal, sailors would also frequent the bars, often bringing with them musical influences they picked up from ports of call as far away as Mexico and Cuba. Jazz musician Joe “King” Oliver honored this legacy with his composition West End Blues in 1932, which was eventually covered by Louis Armstrong, among many others.

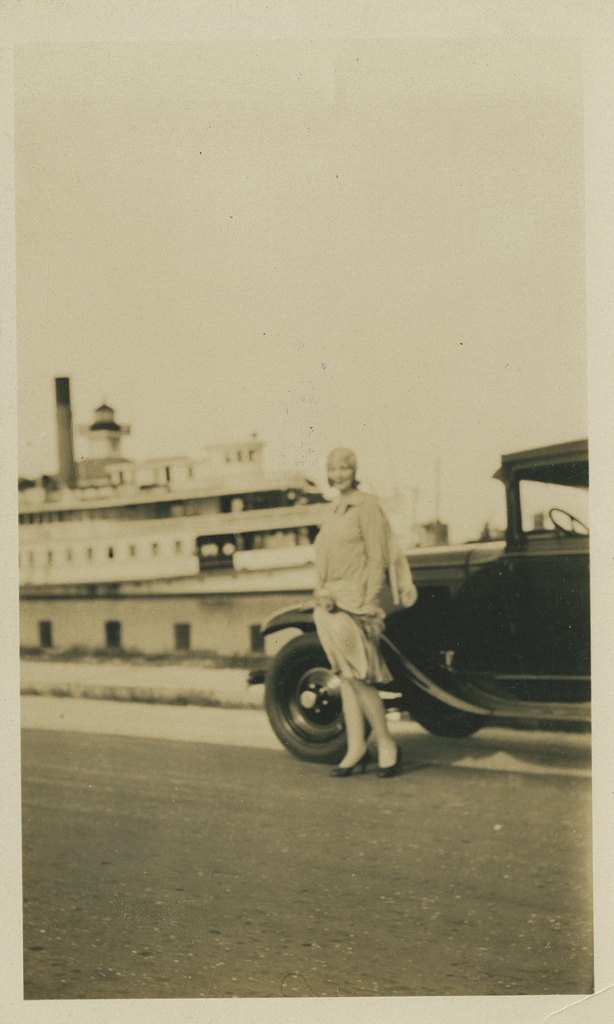

In this photo circa 1920, a steam-powered boat waits at the West End dock to take passengers to Mandeville. In the distance is Southern Yacht Club. Photo by Charles L. Franck. Image from the William Russell Photograph Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection.

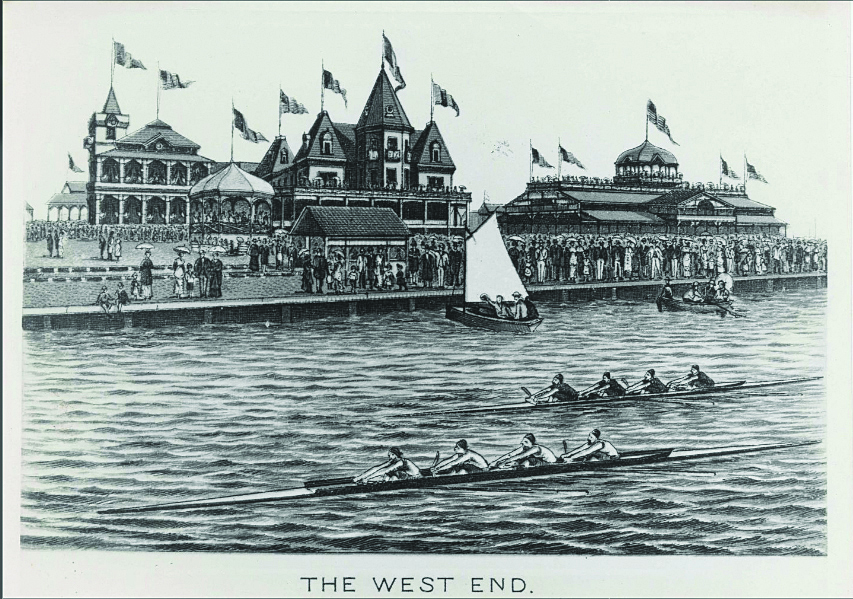

A rowing race at West End. Image courtesy of the Louisiana State Museum Jazz Collection.

A steam-powered tugboard pulls a schooner out of the New Basin Canal 1890

Olympic gold

In 1879, Southern Yacht Club constructed its first clubhouse at West End. Originally formed in 1849 in Pass Christian, Miss., Southern Yacht Club organized in response to the opening of the New York Yacht Club. While Southern held its initial regattas at the upscale coastal hotels of Pass Christian on the Mississippi Sound, the club eventually moved to the St. Charles Hotel in New Orleans. Members then agreed to construct their first clubhouse on Lake Pontchartrain.

The lake has been described as a mini-Gulf of Mexico by sailors, with quizzical winds and fast changing sea-states creating a near-perfect training ground for young sailors, and Southern utilized this natural training ground to great effect. Sailing on Star class dinghies at the 1932 Olympic Games in Los Angeles, Southern Yacht Club sailors took home the first ever gold medal for the United States in competitive sailing. Since then, New Orleanians who trained to sail on Lake Pontchartrain have won two golds and two silver Olympic medals, including the most recent in the 2004 Olympics in Athens, Greece.

One of the more non-descript parcels of waterfront at West End was once the home of this Olympic legacy. Southern’s pen and dry storage for the Star class was located at what is now the termination of the New Basin Canal. Remnants of the boat hoists are still there, and the remaining wooden structure, which is now home to a boat chandlery, is likely the oldest remaining building still standing outside of the Lakefront’s flood protection system.

West End was also the site of the first ever all-female sailing regatta in the Southern United States. “To the utter dismay of the old regime, the gentler sex now was actually learning to sail boats,” wrote Flora K. Scheib in her exhaustive history of Southern Yacht Club. “In the estimation of the flustered old gentlemen of the ‘rocking chair fleet,’ this was nothing short of scandalous.”

On Sept. 3, 1904, four 20-foot Knockabout cabin sloops each helmed and crewed by three young women — but with two men onboard for “safety” — took their start in a steady 6- to 8-knot breeze on the triangular course regularly sailed by men on Lake Pontchartrain. While the “old salts” did not take easily to this change, women of New Orleans led the charge to participate in this growing sport and in doing so, opened the doors for women to compete on the water throughout the South.

A map of West End shows Lakeshore Park circa 1914. Image courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection.

A mid-century aerial view of West End by Charles L. Franck Photographers. Image courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection.

War and Peace

World War II had an impact on every aspect of American life, but at West End, the realities of the war were often visceral. With the oil and gas industry the lifeblood of any nation’s military and war economy, the tankers moving crude and refined oil products were high value targets. Emboldened by their success along the Atlantic Coast in 1941, the Kriegsmarine turned the gaze of their U-boat commanders on the oil-producing Gulf Coast, specifically targeting the shipping waters near the entrance of the Mississippi River.

By the summer of 1942, the war had come to the Gulf of Mexico in full stride. And for residents of coastal fishing communities along the marshy coastlines of Louisiana and Mississippi, huge fireballs on the Gulf horizon would become regular affairs.

Civil Air Patrol seaplanes from Biloxi and Grand Isle flew regularly over New Orleans, filled with burn victims rescued from torpedoed ships. Landing in the Gulf in all weather to extract these people from life rafts or directly from the oil- covered sea, the pilots would then beeline to West End to deposit them into waiting ambulances. A rash of “flying boats” coming in low over the city from the south was an obvious sign that another ship had fallen victim.

With the hospitals in New Orleans filling with front-line casualties, these U-boat attacks were an impossible secret to keep on the Gulf Coast, and civilian sailors of West End signed up en masse to conduct patrols of the Gulf of Mexico, the lake, the Rigolets and other vital waterways. These civilizan patrols would eventually be formalized into the Coast Guard Auxiliary nationwide.

Utilizing shrimp trawlers, fishing vessels, oyster luggers, and all manner of power and sailboats from West End, these Coastal Picket Forces — a precursor to the Coast Guard Auxiliary — were equipped with military radios and armed when possible. They were crucial to the Coast Guard as submarine spotters, and highly effective rescuing survivors from torpedoed ships throughout the war. “A second flotilla of the United States Coast Guard was formally organized at the Southern Yacht Club Tuesday night,” reported the New Orleans States newspaper on Feb. 14, 1940. “It was reported that a third flotilla, comprising motor boats, will complete its organization with a few days.”

For many of the unpaid volunteers of the auxiliary who otherwise could not serve in the military, their time was spent policing and patrolling inland waterways, hunting saboteurs and conducting rescues for run-of-the-mill boating accidents. With these duties filled by the civilian auxiliary, Coast Guard resources could focus on the war effort and chasing U-boats in the Gulf.

Garner H. Tullis “placed his 85-foot, motor-sail yacht Southerly at the disposal of the Coast Guard auxiliary,” reported the New Orleans Item on March 27, 1942. “The Southerly, with a speed of 12 knots under power, will be used in the auxiliary’s patrol of the bridge approaches to the city.”

By 1943, active-duty Coast Guard sailors were drilling with troops along the Lake Pontchartrain seawall in the Higgins landing craft built in New Orleans.

These newfound duties given to civilians to patrol for Uncle Sam didn’t always sit well. Cajun shrimpers in the Rigolets Pass and Barataria Bay initially balked at being boarded by city yachtsmen. But, of particular use to the Navy and Coast Guard were their large offshore-racing schooners and sloops, many of which were docked in West End. They were naturally stealthy, fast, and equipped to handle heavier seas. These racing crews were known to patrol more than 150 miles offshore in the Gulf of Mexico and, on spotting a U-boat, they were asked to maintain contact as long as possible, even if this meant putting themselves at risk.

A woman stands next to a car in front of a boat dock at West End in this photograph circa 1928. Photo from the William Russell Photograph Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection.

West End buildings circa 1892. Image from the photo collection of Dr Edmond Souchon, courtesy of the Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans Jazz Collection.

Evolving legacy

West End’s legacy is constantly evolving. Today, a new $4 million Community Sailing Center is rising to open the lake to all residents, especially those who have historically been unable to access it because of financial or other obstacles. The center trains high school and collegiate sailors from diverse background, exposing them to maritime careers (and perhaps training this city’s next generation of Olympic sailors), as well as bringing wounded military veterans onto the water and offering adaptive sailing for those with disabilities to the city.

Over-the-water dining has returned in the past decade, with 14 restaurants in West End and Bucktown providing the day’s freshest catch and raw oysters to their patrons — with the potential for many more to light their fires.

The Lake Pontchartrain Women’s Sailing Association continues to build on its mission to bring more women onto the water. The boats docked in the new Municipal Yacht Harbor’s state-of-the-art marina are served by a cadre of colorful characters and businesses who form the backbone of West End’s boating culture and maritime economy, while shrimp boats dock in the nearby Bucktown marina.

The Mississippi River may define the city in many ways, but West End is where New Orleanians get beyond the levees and floodwalls and truly interact with the water — and have been doing so for 186-years

On July 4, 1850, 13 sloops and crews took their start from the pier at Dan Hickock’s Lake Hotel at New Orleans’ West End and inaugurated the second oldest distance sailing regatta in the Western Hemisphere – one that is still raced today on the waters of Lake Pontchartrain and the Mississippi Sound.

Spectators lined the piers and waterfront restaurants of West End, then known as New Lake End, and celebrated in this growing hub for waterborne sports and dining. Like the other resorts along the southern shores of Lake Pontchartrain, West End was rapidly becoming a hotbed of recreation and hospitality in the 19th Century, with thousands of spectators lining the shores for rowing competitions and these newfangled sailing regattas — all of which were driven by sports gambling.

Troy Gilbert is an award-winning maritime journalist, author and executive director of the Chefs Brigade, a nonprofit that “connects, organizes and educates across food sectors.”