This story appeared in the June issue of the PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door each month? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

The year 2018 marks the 300th anniversary of the foundation of New Orleans. But like most complex, improvised projects, New Orleans actually came together over many years, and each stage involved various levels of indecision, contingency, discord and serendipity. While most critical events occurred between 1717 and 1722, they can only be understood if we go back to 1682 and earlier. The following timeline aims to contextualize what we mean when we say New Orleans was founded “in” 1718.

PRIOR TO COLONIZATION: Indigenous tribes, including the Houma, Bayougoula, Biloxi, Choctaw, Quinapisa, Acolapissa, Pascagoula and others, inhabit the Mississippi River deltaic plain and adjacent coastal regions, adapting to its seasonal conditions and utilizing its abundant resources.

1519-1543: Three Spanish expeditions explore the region, creating no settlements but increasing European knowledge of Gulf Coast and Mississippi River geography, while unwittingly introducing diseases, which would later cause massive indigenous population declines. Spain moves on to other imperial priorities, but considers this region to be theirs.

LATE 1500s-1600s: French, Dutch, English and Spanish imperialists establish colonies along the East Coast of North America, but mostly steer clear of the Gulf Coast and lower Mississippi.

1682: With the French now well-established in Canada and the Caribbean, French Canadian Robert La Salle, seeking to understand how these colonies are connected, sails westward through the Great Lakes and down the Mississippi. Upon reaching the Gulf of Mexico, La Salle claims the entire watershed for France and names it for his king, Louis IV.

1684: Recognizing the strategic value of controlling the entrance of the Mississippi, La Salle returns to establish a French colony near the river’s mouth. But his expedition gets lost, drifts westward and wrecks along the Texas coast. La Salle’s trusted lieutenant Henri Tonti later succeeds in re-finding the Mississippi, but fails to determine the fate of La Salle — who in fact had long since been murdered by his own men. Louisiana languishes as a French territory for another 15 years.

1680s-1690s: Catching wind that France had laid claim to what Spain considered to be its territory, Spanish authorities in Mexico dispatch a number of expeditions to re-claim the lower Mississippi. Had any succeeded, we would likely have an entirely different history here today.

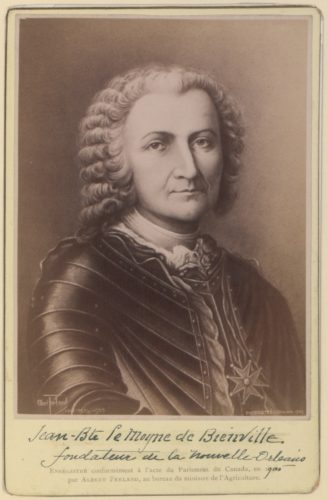

LATE 1697: Hearing rumors of Spanish incursions into Louisiana, France dispatches Montreal’s Le Moyne brothers, Iberville and Bienville, to make good on La Salle’s 1682 claim.

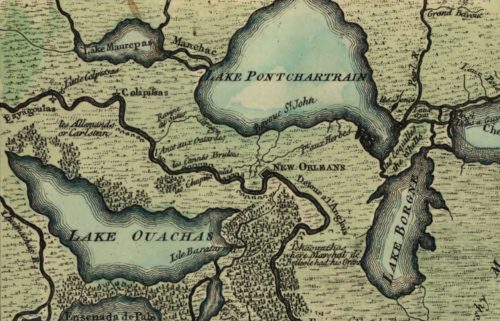

1699: Iberville, Bienville and their crew reconnoiter the lower Mississippi and pass the future New Orleans site in early March, aiming to establish an outpost. But flummoxed by the uncontrolled river and the low, swampy soils, Iberville selects present-day Ocean Springs, Miss., for the colony’s first headquarters, and establishes Fort Maurepas.

AUGUST or SEPTEMBER 1699: While Iberville visits the Bayougoula tribe and proceeds into Natchez territory, Bienville, exploring separately, encounters the English frigate “Carolina Galley,” bent on a mission of settlement. Though only 19 years old, Bienville rebuffs the English captain, who departs peacefully. Had he not, we might have had an English colonial history here. The “English Turn” incident convinces the Le Moyne brothers that a French presence is needed directly upon the lower Mississippi River, as a defensive position.

1700: To that end, Bienville establishes Fort de Mississippi (Boulaye) near present-day Phoenix in Plaquemines Parish. But the simple blockhouse flounders amid soggy soils and high river stages. Bienville has much to learn about building in a delta.

1702: The headquarters of the Louisiana colony moves from Fort Maurepas eastward to Mobile, situated 27 miles up the Mobile River from the present-day Alabama city. European population of the entire Louisiana colony totals around 140 subjects, strewn between Mobile Bay and the Mississippi.

1703-1711: Louisiana’s “dark ages,” a time of inattention, disease, hunger, and failure. Few supply ships arrive from France; key figures Henri Tonti and Iberville die of yellow fever (1704 and 1706); Bienville is forced to abandon Fort de Mississippi for environmental reasons (1707); a settlement aiming to grow wheat along Bayou St. John fails (1708); and Mobile has to be relocated to its present site, due to flooding (1711).

1712: Disillusioned and preoccupied with other matters, France grants a commercial monopoly to financier Antoine Crozat for the development of Louisiana. Crozat hopes to discover gold and silver, raise tobacco and trade with Spain, while the French Crown is content to unburden itself of Louisiana.

1714-1716: French commandant Saint-Denis establishes Natchitoches along the Red River in present-day central Louisiana; La Mothe Cadillac founds Fort Toulouse and Fort Tombecbe on key rivers in Alabama; and Bienville establishes Fort Rosalie at present-day Natchez. Although distant from the future New Orleans area, the three initiatives are the first good news to come out of Louisiana in years.

Over in France…

1714: Scottish investor and economist John Law arrives in Paris, fresh from risky but lucrative financial ventures elsewhere in Europe. Seeking opportunities to test his monetary theories and enrich himself, Law allies himself with noblemen in the French Crown, among them Philippe II, the Duke of Orleans and nephew of the aging King Louis XIV.

1715: King Louis XIV dies; Philippe becomes the Regent of France, acting on behalf of the deceased monarch’s five-year-old great-grandson, Louis XV. Among other things, Philippe finds the kingdom deeply in debt, due largely to Louis XIV’s overspending on palaces and wars. France is nearly broke, and its citizenry demands restitution.

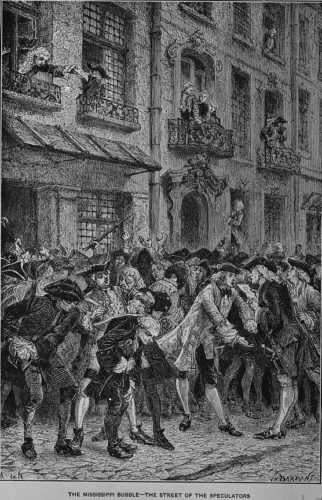

1716: Intrigued by John Law’s economic theories on monetary policy, Philippe authorizes Law to establish the Banque Générale as a centralized bank issuing its own paper currency backed by gold deposits, a novel idea at the time. The bank seems to succeed, though only because the paper bills are over-printed. But the apparent wealth delights Philippe and emboldens Law, a born gambler, to seek another lucrative project.

Meanwhile, back in Louisiana…

AUGUST 13, 1717: After only five years, a frustrated Antoine Crozat formally relinquishes his 15-year commercial monopoly on Louisiana, having failed to find mineral riches, establish plantations or trade with Spanish Mexico. John Law is intrigued to learn of this exotic-sounding land called Louisiana, and connects it with his economic theories.

SUMMER 1717: John Law devises a fantastic scheme which would enrich all involved, based on his idea that paper money need not be backed with real wealth (gold, which was scarce); it could also be backed by commercial wealth — namely the riches that Louisiana could bear under private management. Financing of the company would come from the sale of stock; peopling of the colony would come from recruited or forced emigration of at least 6000 settlers; and labor would come from the hands of 3000 enslaved Africans raising tobacco on plantations. The ensuing profits would enrich shareholders throughout France, not to mention Law and Philippe, while equity in the company would help pay off the national debt.

SEPTEMBER 6, 1717: John Law and his newly created Company of the West formally receive a 25-year monopoly charter to develop Louisiana, with the enthusiastic support of Philippe.

SEPTEMBER 9, 1717: The Company of the West, according to its ledger, “resolved to establish, thirty leagues up the river, a burg which should be called La Nouvelle Orléans, where landing would be possible from either the river or Lake Pontchartrain.” The name of the envisioned city aimed to flatter the project’s royal sponsor, Philippe, the Duke of Orleans, without whom Law’s venture would have been impossible. The specified location implied an alternative to the shoal-prone mouth of the Mississippi, and most likely meant Bayou St. John and Bayou Road, through which access could be gained to a crescent of the river previously identified by Bienville as being favorable for settlement.

AUTUMN 1717: The directive to establish New Orleans makes its way across the Atlantic.

WINTER 1718: Bienville, probably stationed at Mobile, is now in receipt of the directive, and begins preparing six vessels laden with supplies and a crew of 43 men for the voyage to his favored site.

EARLY SPRING 1718: In late March or early April, Bienville’s expedition anchors off today’s upper French Quarter to begin work on New Orleans. “Bienville cut the first cane,” recalled one colonist of that undated moment. Afterwards, 30 workers, all convicts, proceeded to clear the “dense canebrake” probably around present-day 500-600 Decatur Street, at a time when the river flowed closer inland.

1718-1720: Colonials in Louisiana and authorities in Paris question the viability of Bienville’s site selection, and come close to relocating New Orleans, name and all, to Bayou Manchac near Baton Rouge. Others view Mobile or Natchez as superior sites to host the company headquarters and colonial capital, which at this time were on Dauphin Island near Mobile.

1719: First shipment of enslaved people from West Africa arrive at the Company Plantation in present-day Algiers Point. That same spring, high water on the Mississippi River floods New Orleans.

1719-1720: Company headquarters is relocated from storm-damaged Dauphin Island back to old Fort Maurepas (“Old Biloxi,” today’s Ocean Springs) in November 1719, and, two months later, across the bay to New Biloxi (today’s City of Biloxi).

1720-1721: Hearing nothing but discouraging news from Louisiana, investors in Europe divest in John Law’s Company of the West; shares plummet in value, and the “Mississippi Bubble” bursts. Riots rage in Paris, and officials scramble to restructure the enterprise. It later reemerges under the name Company of the Indies.

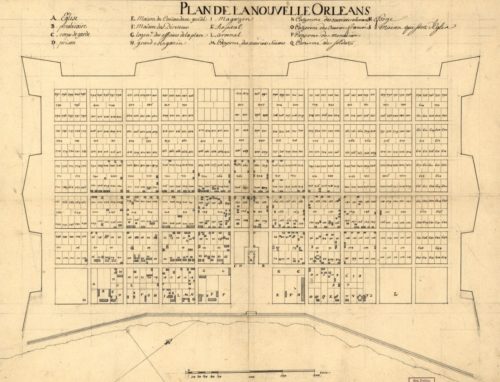

1721: Chief Engineer Le Blond de la Tour designs a fortified town plan for New Biloxi, and dispatches assistant engineer Adrien de Pauger to do the same for now-demoted New Orleans.

Pauger adapts his boss’s Biloxi plan to the geography of the Mississippi’s natural levee, producing a magnificent design for today’s French Quarter, emblazoned with the words La Nouvelle Orléans. He ships a copy to Paris, where it lands into the hands of Philippe II, the Duke of Orleans. French historian Villiers du Terrage, writing in 1920, posited that that map, with the Duke’s name on it, “had weight in the Company’s final decision, since [Philippe], god-father to the new capital, was necessarily flattered to see the project put into effect.” Amid all the bad financial news, New Orleans becomes the only positive news coming out of Louisiana.

Pauger aids the plausibility of New Orleans as capital through his study of river navigability; Council of Regency establishes Capuchin convent in New Orleans; Company designates New Orleans home to Commandant General. Momentum starts to build for Bienville’s city.

DECEMBER 23, 1721: The Company of the Indies officially transfers general management of Louisiana from Biloxi to New Orleans, making it colonial capital and company headquarters.

MAY 26, 1722: Word of the capital-city designation reaches New Orleans. “It appears to me that a better decision could not have been made,” Bienville beamed.

SEPTEMBER 1722: A hurricane destroys most structures in New Orleans, all of which were provisional and haphazardly distributed; their elimination enables Pauger to commence surveying his near grid of streets and blocks into the landscape, creating today’s French Quarter. Recalled one observer a few years later, “New-Orleans … in 1722 … began to assume the appearance of a city, and to increase in population.”

Forty years after La Salle’s initial idea for a colony near the mouth of the Mississippi, the vision is realized.

Note: an earlier version of this timeline appeared in Richard Campanella’s “Cityscapes” column in NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune, and is presented here with permission.