This story appeared in PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

“New approaches from the west — Pontchartrain Expressway,” wrote Robert Moses atop a key section in his Arterial Plan for New Orleans. The famed New York planner had been hired in 1946 by the Louisiana Department of Highways to recommend ways to modernize transportation in greater New Orleans. The plan he delivered covered everything from shipping ports to airports to streetcars, buses, trains, bridges and expressways.

Preservationists today recoil at mention of Moses, for his heavy-handed planning in New York City (my own mother’s circa-1840s Brooklyn neighborhood was obliterated by a Moses housing project), and for calling for a “waterfront expressway” (his term) along the French Quarter riverfront, a wildly controversial plan that preservationists famously defeated in 1969. But no one can deny Moses’ impact on either city, and among his biggest here was his “new approach” for what he dubbed the “Pontchartrain Expressway.”

Scanning maps of the metropolis, Moses’ eyes fell upon a logical pathway between downtown and points west. It was the New Basin Canal, and it had everything a transportation planner would want: a lengthy corridor, with ample girth, oriented in the right direction, under public ownership, with no messy displacements and expropriations, and hardly any opportunity costs, aside from a few leaseholders of canal-side wharfs. “The wide right-of-way along the New Basin Canal,” wrote Moses of the segment from the cemeteries to his envisioned Union Passenger Terminal, “should be used for a through artery; [this] is our unanimous opinion.”

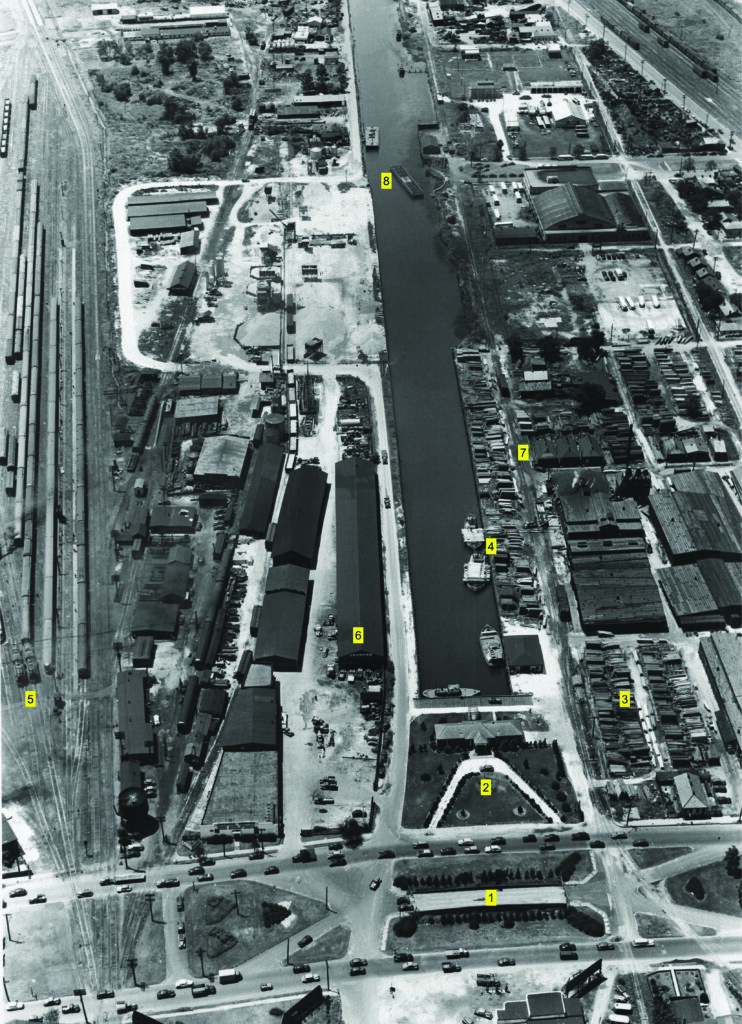

This scene might be wholly unrecognizable to readers, because nearly every visible feature has been radically changed, by either the Pontchartrain Expressway or its later interconnection with Interstate-10 via flyovers and ramps. [1] Here, we see the former turn bridge across the New Basin Canal embedded in the neutral ground of South Claiborne Avenue, between Howard Avenue and Julia Street, frozen in place during the 1938 filling of the 1830s channel. [2] and [3] This crescent driveway leads to the Madison Lumber Company office, whose stacks of wood may be seen to the right. [4] Similar cargo may be seen here, owned by the last leaseholders of the canal’s wharves, and evidence that although the canal had been in decline for decades, it still did its share of business. [5] We see two locomotives pulling cars on the Illinois Central tracks, some of which would proceed to the Louis Sullivan-designed passenger depo on what is now Loyola Avenue at Howard; both the steam locomotives as well as the depo were also in their last days, the latter demolished shortly after the Moses-envisioned Union Passenger Terminal opened in 1954. [6] Note the name “Jahncke” on the shed, named for the company founded by German immigrant Fritz Jahncke in 1905, which came to operate the shipyards in Madisonville. Jahncke did brisk business in cargo storage and transport on the New Basin Canal, so much so that many people called it “Jahncke Basin.” [7] and [8] Amid all the industry and cargo storage, however, note the three shotgun doubles here, vestiges of the days before land-use zoning, when commerce and industry intermixed with residences willy-nilly. Increasingly, as New Orleanians became motorists, they found the canal to be a hated traffic obstacle, forcing them to wait for narrow turn bridges, such as the one visible at 8 (out of service at this point), at what is now South Galvez.

For the segment that extended through Lakeview, Moses recommended that the waterway “should be kept open, both because of its scenic attraction [and] its usefulness for shipping and boating.” Yet he also eyed the trajectory for an artery that would make West End the terminus of a “causeway across the lake on a line running from near the end of the New Basin Canal to Green Point (near) Mandeville.”

In time, the channel in Lakeview was filled in to become today’s New Basin Canal Park, while the Lake Pontchartrain Causeway was shifted 2.4 miles westward into Jefferson Parish and built directly to Mandeville. Nevertheless, it is striking how much an antebellum barge canal would influence Moses’ recommendations and shape our daily movements today.

The New Basin Canal originated from an earlier version of westward/lakeward access, when private investors in 1830 envisioned digging a navigation canal to connect New Orleans with the valuable natural resources of the Pontchartrain Basin. The investors formed an “improvement bank” — a financial institution missioned to build and operate private infrastructure for profit — and on March 5, 1831, attained a charter from the Louisiana Legislature for the New Orleans Canal & Banking Company. In what would become one of the city’s largest projects to date, they planned to excavate a 60-foot-wide shipping channel with six feet of depth, bordered by guide levees, topped with a toll road and tow path, with a turning basin at the city end and a harbor on the lakeshore. The company would have exclusive rights to charge tolls and lease space along the canal for 35 years, after which the asset would become state property — a key stipulation that would later make the channel available for a public highway.

Raising more than $4 million in just a few months, the N.O.C.&B.C. now had to plot the route and acquire rights of way. The turning basin, called Mobile Landing, would be located where Triton Walk (now Howard Avenue) meets today’s Loyola Avenue. From there, the right of way would span 300 feet in width and run in three angled segments across six miles, with key land acquisitions from the Macarty (McCarty) family informing the route selection through what at the time was Jefferson Parish.

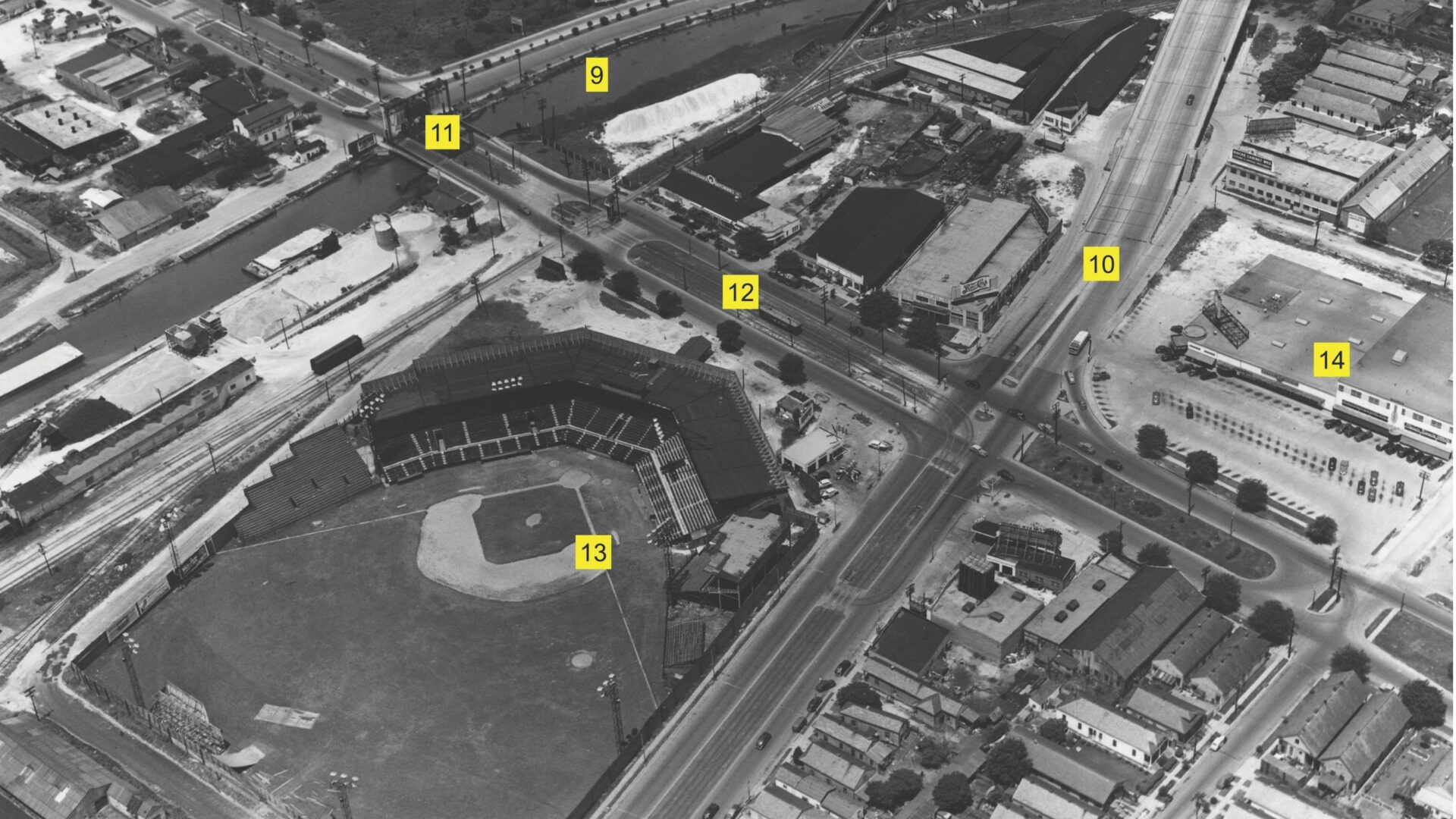

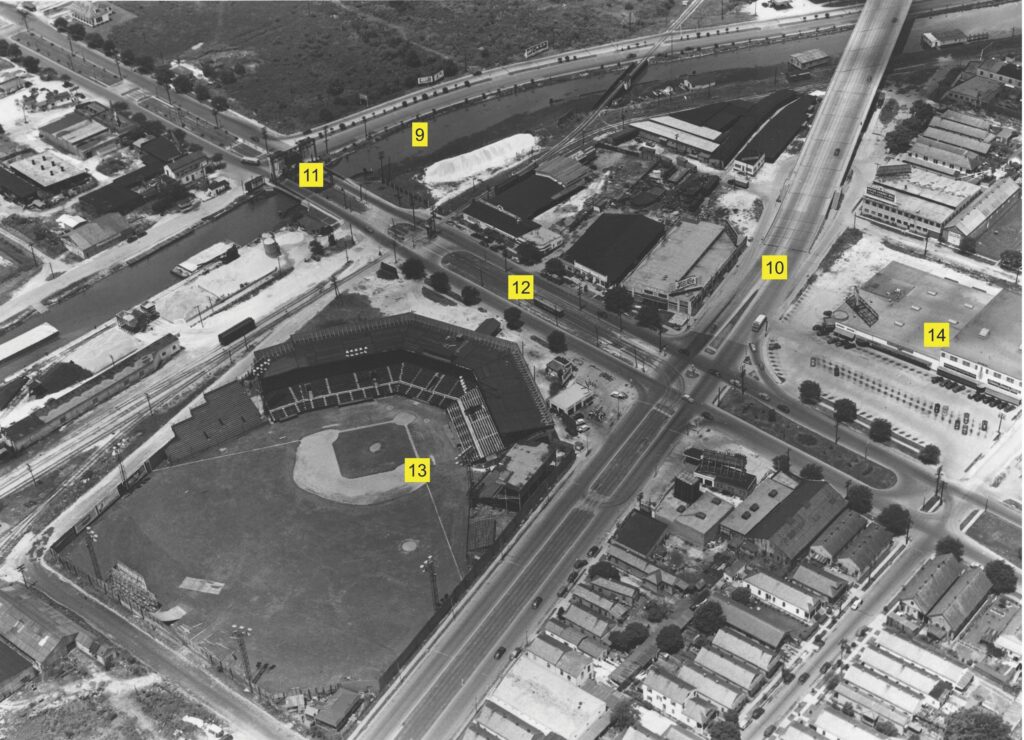

In this scene, we see the New Basin Canal [9] and Airline Highway (Tulane Avenue [10]) crossed by Carrollton Avenue (note bridge at [11] and streetcar at [12]), where Pelican Stadium drew crowds from its construction in 1915 as Heinemann Park to its demolition in 1957. In addition to minor-league players with the Pelicans and Negro League teams, here played baseball legends, such as Babe Ruth, Jackie Robinson and Hank Aaron during spring-training exhibition games. If you go to Chick-fil-A, you’re on third base [13]. Note the early strip mall at [14], still in operation, where in 1950 operated an A&P Super Market and the Mid City Bowling Lanes — today’s Rock-n-Bowl, later relocated. (1950s photo provided to Richard Campanella by Felton Suthon of Metairie, courtesy of Modjeski and Masters and the Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development. 2020 image courtesy of Google Earth.)

For labor, N.O.C.&B.C. recruited thousands of Irish “ditchers” who, under brutal conditions, dug the channel in sections separated by gates, using the soil to build the guide levees and roads. As they progressed, workers would remove the gate and let the water flush through.

The first half of the canal, from Mobile Landing to Metairie Road (City Park Avenue), was completed in August 1834, and the second half through the swamps of future Lakeview was finished in 1835. Finishing touches were put on the lake harbor and tow paths in 1836, and once fully operating by 1838, the canal attracted a steady stream of vessels bearing shells, sand, timber, firewood, charcoal, resin, produce, game, finfish and shellfish. Some people called it the Basin Canal or the New Orleans Canal, but most called it the “New” Basin Canal, to distinguish its superior services from the circa-1794 Carondelet Canal, now dubbed the Old Basin Canal. Whatever its name, the canal and toll road practically minted money, producing $405,563 for the N.O.C.&B.C. in just the first year, roughly $10 million today.

Thirty-five years after its 1831 charter, the N.O.C.&B.C., as stipulated, relinquished control of the New Basin Canal to the State of Louisiana (1866). Following numerous court cases over issues such as toll rates and leasing rights, the state-run waterway remained vital, used by thousands of luggers, schooners, and tug-pushed vessels annually, bearing millions of bricks and board feet of lumber and thousands of cords of firewood, as well as tons of shells, charcoal, sand, and resin.

By the 1920s, however, trains and trucks did a more efficient job of delivering cargo to the city, and the old cross-town canals came to be seen as malodorous nuisances and obstacles to traffic. In 1936, the state passed a constitutional amendment to start closing the New Basin Canal, and in July of the following year, workers began filling the turning basin, and proceeded on to South Claiborne in 1938. Work stopped when World War II broke out, but resumed in the early 1950s, thanks in part to Moses’ plan to use the corridor for the Pontchartrain Expressway in its approach to the planned Greater New Orleans Mississippi River Bridge.

In the last edition of Preservation in Print, we examined the 52 historical buildings lost to the riverfront segment of the Pontchartrain Expressway, using a low-level aerial photograph captured in 1950 by the Louisiana Department of Highways (now Transportation and Development). In this edition, we look at three 1950 frames of the New Basin Canal, digital copies of which were shared with me by Felton Suthon, who worked for the engineering firm Modjeski and Masters for 15 years, and to whom I express gratitude.

Editor’s Note: This article follows up on the “Streetscapes” column published in the April/May 2024 issue of Preservation in Print, which recounted the impacts of the Pontchartrain Expressway on today’s Warehouse and Lower Garden Districts. In this issue, we examine its effects farther inland.

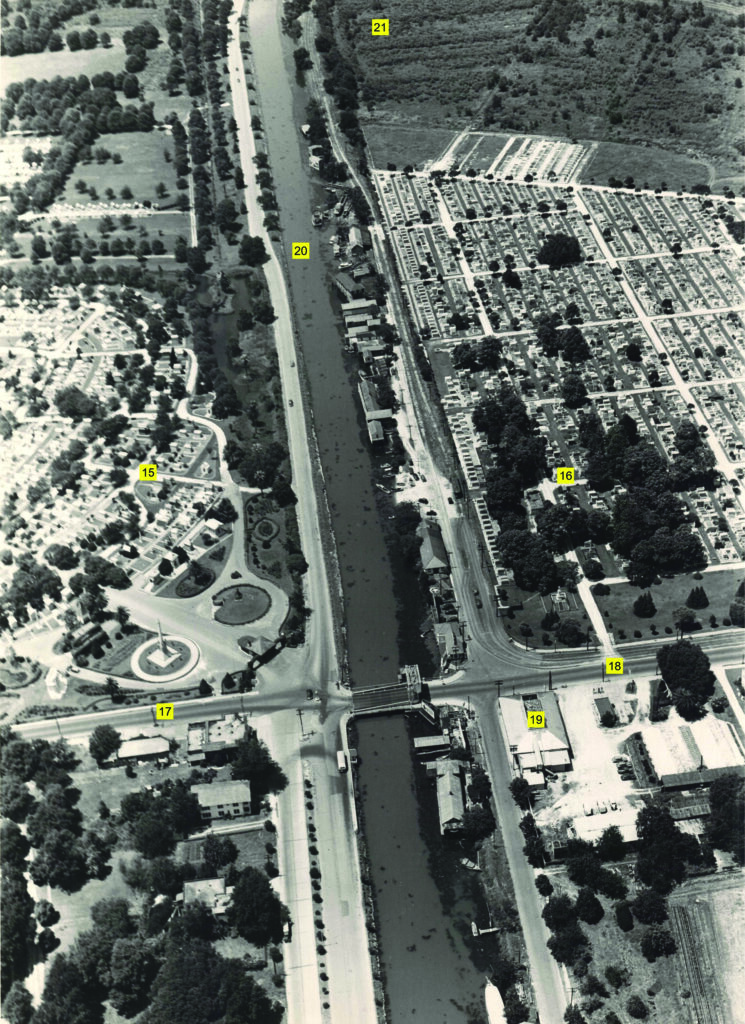

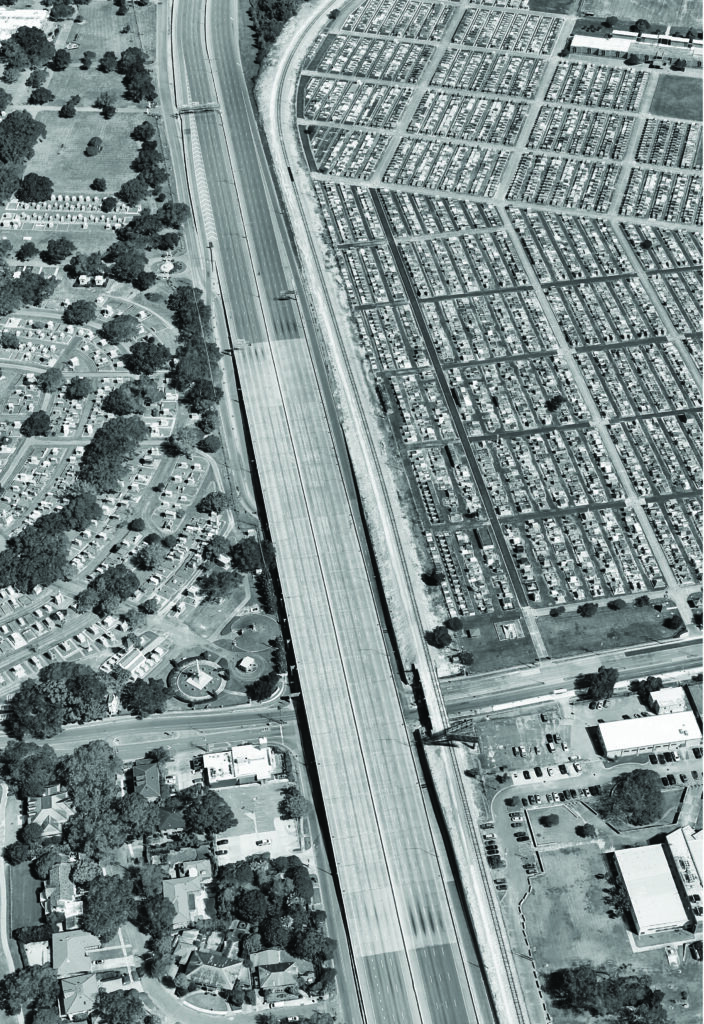

In this scene, we can readily recognize Metairie Cemetery [15] and Greenwood Cemetery [16], where the Metairie Ridge topographic feature historically enabled Metairie Road [17] and City Park Avenue [18] to form a passageway across the swamps. Digging across the ridge in the 1830s represented some of the toughest ditching in 1834, but it also represented the only section that was not mired in soggy swampland. Being roughly halfway between Mobile Landing and West End, this point became a stopover, home to a number of eateries and joints, including the famed Halfway House jazz dance hall [19], opened in 1914 and demolished in 2010. This scene gives us a sense of how the 60-foot-wide New Basin Canal [20], set within its 300-foot-wide right-of-way, provided enough space for the Pontchartrain Expressway and I-10. At [21], we see what appear to be fallow truck farms, giving an idea of the rural environs through which the New Basin Canal traversed for most of its history. (1950s photo provided to Richard Campanella by Felton Suthon of Metairie, courtesy of Modjeski and Masters and the Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development. 2020 image courtesy of Google Earth.)

Streetscapes is written by Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture and author of Draining New Orleans; The West Bank of Greater New Orleans; and Bourbon Street: A History from LSU Press, and The Cottage on Tchoupitoulas from the Preservation Resource Center. Campanella may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, or @nolacampanella on X.