This story appeared in the June issue of the PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door each month? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

Inconceivable as it may seem today, New Orleans’ political and business elite fought long and hard to build an expressway through the French Quarter some 20 years after World War II.

It was a fight fraught with paradox and irony.

Preservationists led the ultimately successful battle to save the cherished historic district, and in doing so, broke new ground. They put New Orleans at the head of a pack of cities creating more sophisticated ways in which transportation issues shape the urban experience. By fending off the highway, they laid the groundwork for the kind of revival that today has made inner-city neighborhoods more vigorous, both culturally and economically, than the suburbs to which an earlier generation had fled.

In hindsight, it’s sobering to realize how close New Orleans came to destroying itself.

THE HISTORY

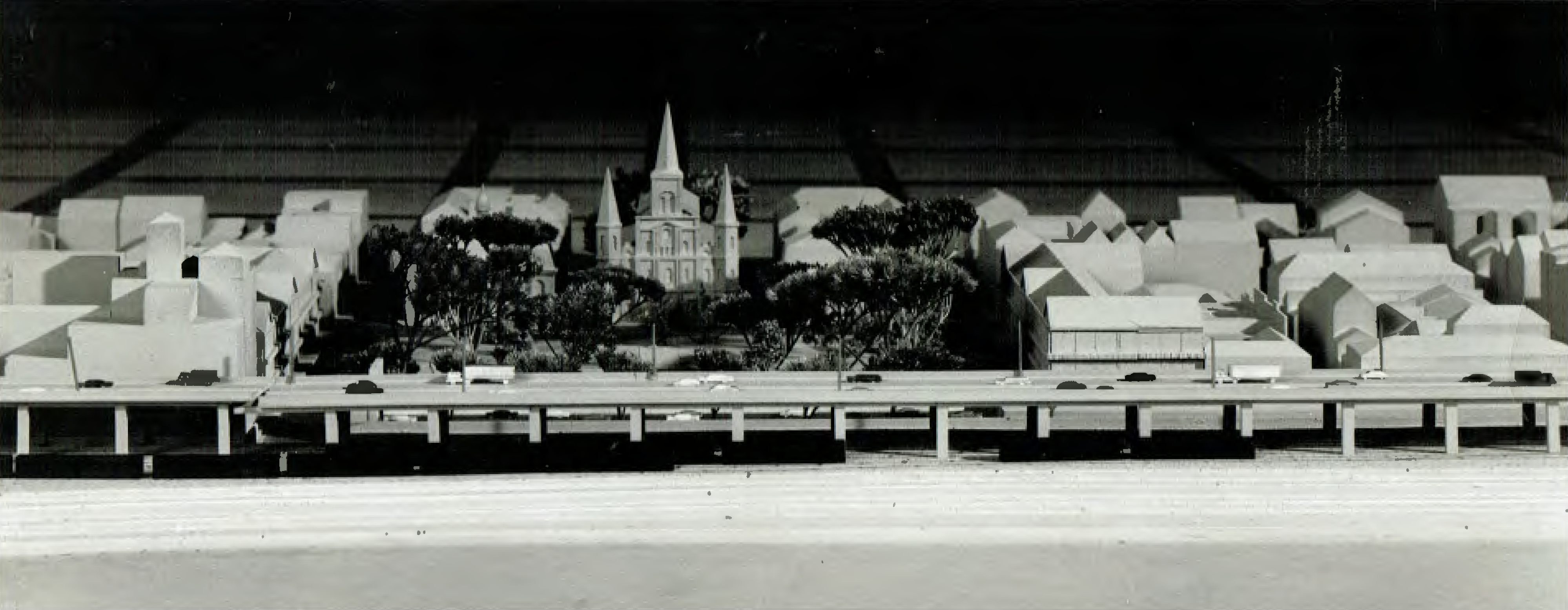

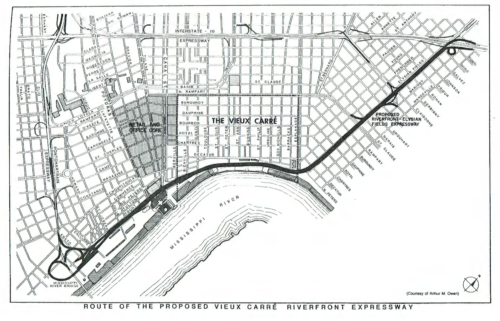

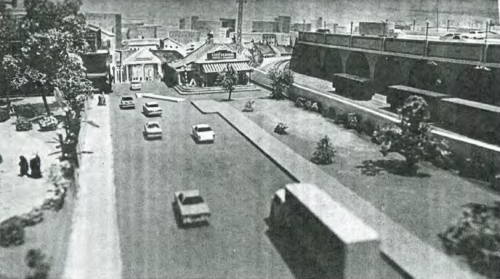

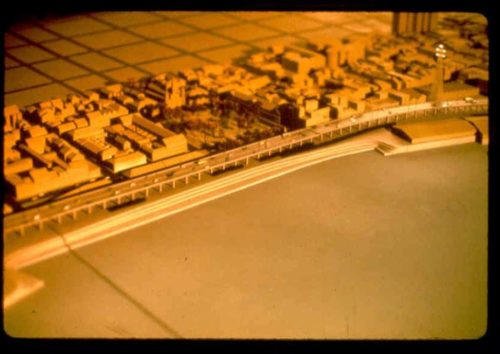

In 1946, in a quest for ideas to “modernize” New Orleans’ transportation grid, The Louisiana Highway Department hired New York’s almighty transportation czar, Robert Moses, as a consultant. Moses was already becoming notorious; his enthusiasm for cars and highways was as boundless as his indifference to the virtues of public transit. His New Orleans’ blueprint called for a Riverfront Expressway — an elevated six-lane expressway, 40-feet high and 108-feet wide — separating the French Quarter from its frontage on the Mississippi River.

Fast-forward 10 years. By 1956, the federal government had unveiled a program to spend $41 billion to build 41,000 miles of “defense highways” to connect cities with a population of 50,000 or more. By 1969, the price tag had jumped to $104 billion, making it the largest public works project in U.S. history. With the federal government picking up 90 percent of the cost, New Orleans — like every other city — was salivating for its piece of the pie.

Freeways would be the “life blood” of the city, proponents argued. They promised deliverance from increasingly congested downtowns. Civic pride was at stake. Give up the money, and it would just go to Houston, Dallas and Atlanta, cities that were preparing to wrap themselves in ribbons of elevated highway. New Orleans needed to keep up in the name of progress.

THE PROPONENTS

Enter the Central Area Committee (CAC). Formed in 1957 under the aegis of the local Chamber of Commerce, the CAC’s primary concern was the automobile congestion that seemed to be choking the Central Business District (CBD), weakening the magnetism of the big department stores and irritating commuters. The argument was that expressways would jolt a fading downtown back to its former vitality and stanch the worrisome flow of people moving out to suburbia.

Leaning heavily on Moses’ blueprint, the CAC produced a “study,” a one-sided thesis titled “A Prospectus for Revitalizing New Orleans Central Business District.” It recommended an expressway along the Vieux Carré riverfront fed by six-lane thoroughfares down Elysian Fields Avenue, and a later addition to the plan had it continuing Uptown to a new river bridge at Napoleon Avenue. It included topping Claiborne Avenue with the elevated Interstate that actually got built, bisecting and causing irrevocable harm to Tremé, the city’s oldest black neighborhood. The Claiborne Avenue elevated expressway, often misconstrued as the default after the riverfront portion was defeated, was in fact Interstate 10’s primary route through New Orleans and was under construction while the riverfront route was still embattled.

Incredibly, the city’s business and political elite spent years fighting doggedly for this highway plan. The high-powered proponents included The Times-Picayune, the Chamber of Commerce, WWL-TV, the Bureau of Governmental Research, the New Orleans Levee Board, the City Planning Commission, business titan Richard Freeman, Mayor Victor Schiro and Councilman Moon Landrieu.

THE OPPONENTS

A “Freeway War” was heating up across the nation by the 1960s. The first noteworthy opposition had cropped up when historically significant sites became at risk: Independence Hall in Philadelphia and Beacon Hill in Boston, to name just two. In New York City, the visionary urbanist Jane Jacobs had begun her battle, organizing fellow citizens to block Moses’ plan to bulldoze the West Village, and later to plow a crosstown Interstate through the East Village, Little Italy and what would become SoHo.

Preservationists also were a significant force in New Orleans. They had saved the Vieux Carré from extinction by pioneering the tout ensemble concept as an alternative to fighting building-by-building for neighborhood preservation. As early as 1961, Louisiana Landmarks Society and Vieux Carré Property Owners and Associates passed resolutions opposing the Moses plan along the French Quarter riverfront. The opponents counted in their ranks leading architects, authors and activists; stalwarts like Martha Robinson, Harnett T. Kane, Sam Wilson, Ray Boudreaux, John W. Lawrence, and support from the weekly Vieux Carré Courier.

But resolutions weren’t enough. A legal strategy was needed.

In 1965, on Christmas break from college, two young lawyers, William E. Borah and Richard O. Baumbach, Jr. got wind of the expressway plan and were sufficiently appalled — enough to suspend their respective graduate programs and join the fight. Their efforts caught the eye of Edgar Stern Jr., scion of the Stern/Rosenwald family of Longue Vue fame. As employees of the Stern Family Fund, a progressive national foundation involved in urban issues, Borah and Baumbach were given carte blanche to study cities across the nation threatened by highway interests.

As with the CAC’s “Prospectus,” most of the studies supporting unfettered freeway expansion were little more than one-sided arguments buttressed by unproven assumptions — above all that highways would revive downtowns rather than hasten flight to the suburbs. But one in particular caught Borah’s and Baumbach’s attention, a study of highway plans around Washington, D.C., by Boston-based consultant Arthur D. Little. Unlike others, this study actually pushed back against some of the assumptions embraced by the highway interests who had hired the firm in hopes it would merely rubberstamp their plans.

Again with Stern funding, Little was hired to study the New Orleans expressway plan, which was found to be deeply flawed. It had been shaped by only one preconception, the CAC’s focus on easing access to the CBD and its underlying assumption that freeways were the solution. Ignoring federal requirements, the CAC study had given no thought to the transportation needs of the city as a whole and had failed to cite other cities’ relevant experiences. Additionally, it had failed to include an analysis of public vs. private transportation modes, or combinations thereof, as required by the federal Bureau of Public Roads. Most importantly, Little condemned the CAC study for clinging to the 1946 Moses map and failing to consider alternative routes.

As opposition grew, the proposed highway gyrated through various iterations: elevated, partially elevated, at grade, below-ground, etc. But the elevated stretch directly in front of Jackson Square remained a constant. In 1964, so confident were city officials in ultimately getting their expressway, they funded construction of a $1.3 million tunnel under the Rivergate Exhibition Facility without federal approval or a guarantee of reimbursement. As a matter of aesthetics, they were willing to conceal the freeway at Poydras Street near the World Trade Center — but not in front of St. Louis Cathedral.

TAKING THE FIGHT TO WASHINGTON

With the Arthur D. Little Study as inspiration, Borah and Baumbach reached what would turn out to be a pivotal realization. There was little chance that the preservationists could prevail at the state or municipal level. To have a real shot at stopping the Riverfront Expressway, they needed to take the fight to the federal level — to Congress and the courts. To guide them into the upper echelons of U.S. transportation policy, Borah and Baumbach convinced the Sterns to engage as their legal counsel Louis F. Oberdorfer, of the powerful Washington firm Wilmer, Cutler and Pickering. The two young lawyers then began working with Oberdorfer’s team, preparing arguments demonstrating that the CAC had not complied with rules that needed to be respected if the feds were going to pick up that all-important 90 percent of the bill.

The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1962 required a “continuing comprehensive planning process” and a long-range transportation plan. The Department of Transportation Act of 1966 required studying alternative routes, stipulated that the secretary should not approve any project that requires the use of land from a historic site unless there is no “feasible” or “prudent” alternative, and included that all possible planning must be done to minimize the harm to the historic site. Furthermore, the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 required that the newly formed Advisory Council of Historic Preservation be allowed to review and comment on any project using federal funds that impinged on a historic district. Given that these stipulations had not been met, the Oberdorfer team argued that the entire planning process was invalid.

The battle drew national media attention. Articles appeared in major magazines and newspapers across the country (though not the New Orleans dailies), educating America about the matchless value of the French Quarter and how an expressway would irreparably harm it. The Quarter was a national treasure and locals had no right to destroy it, mainstream media reasoned.

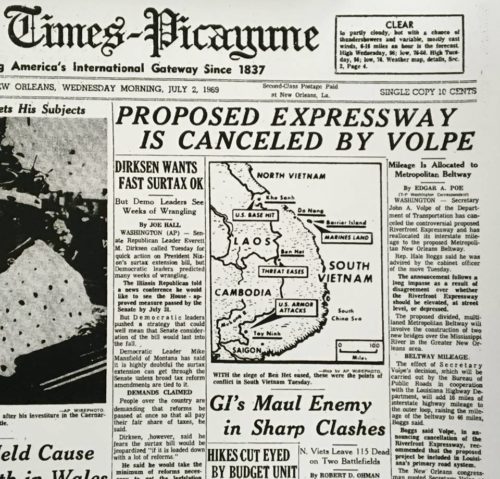

The year 1969 brought the chaotic battle to its culmination. With the Nixon administration about to take office, and John A. Volpe, an unknown commodity, set to become Secretary of Transportation, proponents urgently wanted approval before outgoing Federal Highway Administrator Lowell Bridwell left office. In a tense, seven-hour New Orleans City Council meeting, the vote ended 4-3 in favor of the expressway. Eight days later, with only three days left in office, Bridwell approved the all-important federal funding for the project.

Within another 11 days, federal approval was withdrawn. The Advisory Council asserted its right to review and comment on the expressway plan under the National Historic Preservation Act. This gave the opponents what looked like their last shot.

After hearing testimony in Washington and a subsequent on-site visit in New Orleans, the Advisory Council determined that the freeway would have a serious adverse effect on the French Quarter’s tout ensemble.

With that report, both sides anxiously petitioned for a meeting with Secretary Volpe. The federal Department of Transportation sent James Braman to meet with the New Orleanians and prepare a report.

In June 6, 1969, proponents, positioned in Mayor Schiro’s office, and opponents, meeting later at the Presbytere on Jackson Square, presented powerful arguments in support of their diametrically opposite positions. John Vardaman of Wilmer, Cutler and Pickering rehashed the numerous ways in which the CAC and highway interests were out of compliance with federal rules, concluding with, “Mr. Secretary, the expressway opponents may not have the newspaper on their side. They may not have the mayor on their side. But, in my opinion, they do have the law on their side.”

Less than a month later, jubilant preservationists were shouting hallelujah. Volpe cancelled the Vieux Carré expressway on July 1, confirming that “it would have seriously impaired the historic quality of New Orleans’ famed French Quarter.” Echoing the argument shaped by the Oberdorfer legal team, Volpe cited the failure to study alternate routes or to factor in mass transportation as evidence of New Orleans’ woeful lack of comprehensive transportation planning. In a stunning rebuff to the CAC’s misbegotten faith in highways as the solution to congestion, Volpe noted data from other cities demonstrating that the more highways are built, the greater the gridlock.

In turning back “the highwaymen,” as Borah called them, New Orleans was ahead of the curve, for a change. The Washington Post declared the “Battle of New Orleans” a turning point in the Freeway War. The expressway was the first segment of the Interstate Highway System cancelled for environmental reasons, Business Week noted.

Recently, in cutting a deal with the Port of New Orleans to relinquish the wharves at Governor Nicholls Street and Esplanade Avenue for public use, former Mayor Mitch Landrieu lauded New Orleans for reassembling over three miles of public land, the nation’s largest contiguous riverfront park.

There was every reason to join Landrieu in celebrating that achievement. But let no one forget the debt we owe to the relentlessly wily band of preservationists who kept that riverfront from being paved a half-century ago.

SANDRA STOKES gratefully acknowledges Jed Horne for his help with this article. Horne has written the preface to a new edition of Second Battle of New Orleans: A History of the Vieux Carré Riverfront-Expressway Controversy, Richard Baumbach, Jr. and William Borah’s account of the fight against the expressway. The book, long out of print, is being republished in an updated edition by University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press.