This story appeared in the April issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

If there is one commonality amongst readers of Preservation in Print, it is an abiding love for old New Orleans buildings, the heartstrings of which tie together deep interests in architecture and history, an eye for good design and an argument for sustainable urbanism.

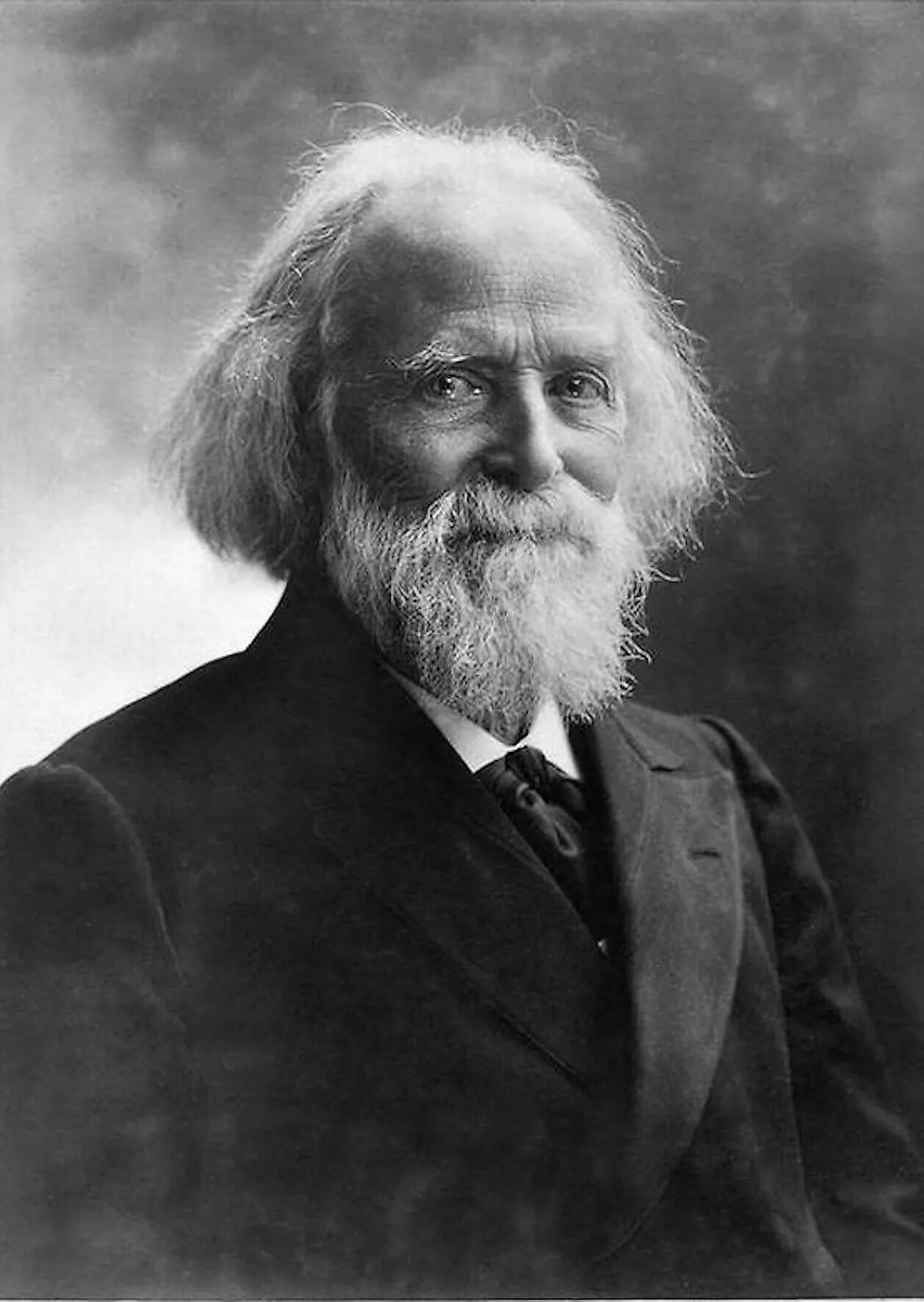

So, it may be rather disquieting to hear a voice that is perfectly blasé, and sometimes utterly contemptuous, of our historical built environment, especially at the time of its peak production of the 1850s. But in the spirit of intellectual diversity, it’s worth listening to the critical voice of Jacques Élisée Reclus (1830-1905), the French scholar whose two years in Louisiana proved influential in his becoming a premier academic geographer and political theorist.

Born to a Protestant pastor in southwestern France, Élisée Reclus fled his homeland in opposition to the 1851 coup d’etat of Napoleon III and made his way to England and Ireland before deciding to try America. Failing to secure a position on a steamer to New York, “he managed to gain a berth as a cook on a sailing ship bound for New Orleans,” wrote the late geographer Gary S. Dunbar in a 1982 article. “He rationalized that if he were to drown, he would at least drown in warm water, and that he could spend the winter out in the open if necessary in New Orleans.” The year was 1853.

Advertisement

Peering through fog as his vessel entered the lower Mississippi River, Reclus took detailed notes of everything he saw in the turbid delta, as reeds and marsh gave way to cypress swamps with “Spanish beard” (moss) and tangled briars. “The first plantations appear above Fort Jackson, a type of small earthen fort that the patriots of Louisiana like to think of as impregnable,” wrote Reclus, in a 1993 translation by Camille Martin and John Clark. “Next come fields of cane like vast blocks of greenery, isolated magnolias, and alleys of pecan trees and of chinaberries. There are also wooden [plantation] houses painted with a red or white wash and perched on two- or three-foot pilings of masonry above the always moist soil, and Negroes’ quarters resembling beehives, half-buried in the tall grass of a garden.”

Soon there appeared on the left (east) bank “a commemorative column in honor of the Battle of New Orleans,” the initial section of the marble obelisk at Chalmette Battlefield. Then in the distance he eyed a “thick black atmosphere…over the distant horizon,” beneath which “the buildings of the southern metropolis came into sight…belfry after belfry, house after house, ship after ship[:] the luggers, the schooners, the high steamboats resembling gigantic stabled mastodons, then the three-masters arranged along the bank in an interminable avenue.” It was the largest city in the South, New Orleans, and one of the busiest ports in the hemisphere. “Behind this vast semi-circle of masts and yards were wooden jetties crowded with all sorts of merchandise, carriages and wagons bouncing along the pavement, and finally, houses of brick, of wood, and of stone, gigantic billboards, factory fumes, and bustling streets.”

Reclus took a job as a tutor for Septime Fortier’s children at Félicité Plantation on the right (west) bank of St. James Parish. That live-in position gave the young progressive an up-close view of plantation slavery, which he found “utterly repugnant,” according to Dunbar; “he deplored the dehumanizing effects of slavery on the whites, as well as on the blacks.” Reclus was even more horrified by the slave trade, New Orleans ranking as the largest such marketplace in the nation. His description of a slave auction at Bank’s Arcade on Magazine Street, translated by Martin and Clark, is perfectly harrowing. “Thus all the Negroes of Louisiana pass in turn on this fateful table,” he wrote, “children…separated from their mothers, young girls subjected to the stares of two thousand spectators and sold by the pound…obliged to remain cheerful under threat of the whip, and the elderly [who] are deprived of the most vile and pitiful honor, that of bringing a good price.”

The quotidian cruelty of slavery likely soured Reclus’ broader views of Louisiana society, and it probably didn’t help that he had arrived during New Orleans’ worst-ever yellow fever epidemic, summer 1853, which would eventually kill nearly one out of every 10 people in the city. Reclus himself contracted the disease, and attributed his survival to vegetarianism — one of his many behavioral restraints which he equated with moral rigor.

New Orleanians, on the other hand, seemed not to partake of any personal discipline, and in his private writings Reclus denounced them for their indulgence, vice, torpor and selective policing, in which most murders went ignored while many Black people were imprisoned for little or no reason. “How can an enduring prosperity be built on evil,” he pondered, counting the 2,500 grog-soaked dens of iniquity where so much of the sin arose. “Every big hotel opens its entire first floor [for] the national vice of drunkenness,” all beneath “a large rotunda… where rogues rendezvous with dupes.”

Photo 1: Jacques Élisée Reclus (1830-1905), a French scholar whose two years in Louisiana proved influential in his becoming a premier academic geographer and political theorist. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia Commons. Photo 2: Reclus penned A Voyage to New Orleans in the mid-1800s.

Yet Reclus also recognized warmth and hospitality among many locals, and credited them for enough laudable traits to set himself apart from those many finger-wagging judmentalists who came to New Orleans predisposed by political or religious agendas. Reclus was no objective observer, but he was a budding social scientist and political theorist, and his critiques were not purely prejudicial.

Which brings us to his take on architecture, city management and the built environment. “For a long time, all the houses of New Orleans were aimple huts made of wood, and in spite of its extent, the whole city had the appearance of a huge fairground.” Now, he wrote, even with brick construction, “the principal agent of change in the city is not the aesthetic taste of the owners, but rather fire.” During one stretch of May, “not one night passes in which the alarm does not call, [and] the purple reflections of four or five fires color the sky…. It has been calculated that in the city of New York alone, flames annually destroy as many buildings as in all of France. In New Orleans, a city five to six times less populated than New York, the amount of fires is relatively greater still.” One night he saw “seven large steamships burned simultaneously. It was an awesome sight[,] a sea of flames…. Forty-two persons were burned alive before a rescue attempt was organized[;] the nightwatchmen are far too few in number to be of much use in preventing disasters.

Advertisement

“As for the public buildings,” he continued, “they are for the most part devoid of any architectural merit. The train stations are wretched hangars blackened with smoke, the theaters are mostly dumps at the mercy of fire, and the churches, with the exception of a type of mosque built by the Jesuits [Church of the Immaculate Conception on Baronne Street, new at the time and rebuilt in 1927] are but large pretentious hovels. Moreover, of all the public buildings, the churches are most subject to the risk of fire or demolition.”

Reclus said next to nothing about the recently refurbished Jackson Square, with its rebuilt St. Louis Cathedral, new Pontalba apartments, renovated Cabildo and Presbytere, and newly landscaped park. What he did say was that “public promenades…do not exist[;] the only tree inside the city is a solitary date palm planted sixty years ago by an old monk,” and that the “bronze statue [of] Andrew Jackson…has no other merit than that of being colossal and of having cost a million.” No surprise, Reclus snorted, since “in a society of this type, art cannot be seriously cultivated…. Rich individuals confine themselves to whitewashing the trees in their gardens, [which] has the double advantage of being pleasing to their sight and of costing very little.”

Reclus served as a tutor for Septime Fortier’s children at Felicity Plantation in St. James Parish. Photo courtesy of anthonyturducken.

Despite it all, Reclus’ two-year sojourn in Louisiana left him intellectually inspired, particularly in the fields of physical geography and political theory. In a letter he wrote just prior to his departure in late 1855, he revealed he had been “pregnant for a long time with a geographical Mistouflet” — that is, “a lively child,” according to Dunbar’s translation — “that I wish to bring forth in the form of a book; I have already scribbled enough, but that doesn’t satisfy me.” His subsequent ventures into the Caribbean and South America yielded more food for thought, which laid the groundwork for a professional career in geography and as an outspoken voice against governmental power — something surely informed by what he saw of legally sanctioned slavery in Louisiana.

Elisée Reclus’ experiences here, according to the geographer Dunbar, “were of inestimable value to him,” and as he “settled down in Paris, he began to reap the harvest of the seed that he had sown in Louisiana, [becoming] the most prolific geographer of modern times and a leading figure in the European anarchist movement.” His experience informed his magnum opus, the two-volume physical geography La Terre published in 1869, as well as various later publications. Elisée Reclus’ died in 1905, never having returned to his scorned muse.

Richard Campanella is a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture and author of The West Bank of Greater New Orleans; Cityscapes of New Orleans; Bourbon Street: A History; and other books. Campanella may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, or@nolacampanella on Twitter.

Advertisements