300 Years of an Evolving City: Exploring the History that Shaped the New Orleans that Stands Today

The five thousand residents of of New Orleans began the day — Good Friday, March 21, 1788 — in homes and businesses that lay in ashes by nightfall. Most occupied wooden structures roofed with highly flammable cypress shakes or palm thatch. Only the better buildings were of masonry or had tile roofs. All were placed willy-nilly on their lots among huts, chicken coops, privies, sheds, trees and gardens. The Spanish Colonial town was a fire-trap.

About 1:30 in the afternoon, a fire broke out in the Chartres Street home of provincial treasurer Don Joseph Vincente Nunez. According to official records, it “originated by the burning of a wooden cabinet,” but a more vivid account asserts that Nunez erected an altar in his home to commemorate Good Friday and during dinner, neglected numerous burning tapers that set fire to the ceiling. Said the visiting merchant, “From thence proceeded the destruction of the most regular well governed small city in the Western world.”

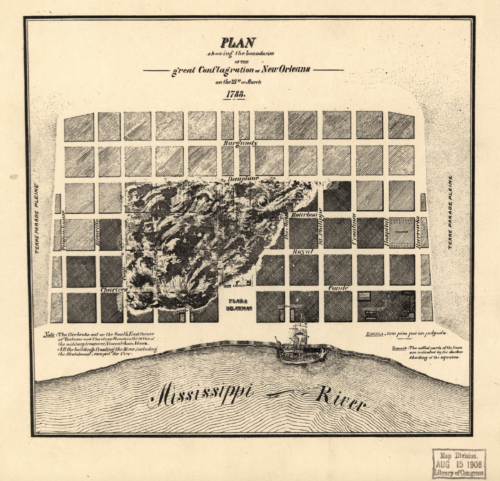

The fire raged for hours. Driven by a strong south wind and skipping across the crowded lots, progress was so rapid that little could be saved. Efforts to extinguish the flames were in vain, but no lives were lost. Cabildo minutes record that “4/5 of the populated section of this City was reduced to ashes.” Along with about 850 shops, warehouses and homes, the flames consumed the city’s civic and religious center, including the fire pumps stored there.

Governor Miro reported the destruction of St. Louis Parish Church, the Presbytère, the Cabildo, the guard house, and the armory. Prisoners housed in the public jail were saved only by determined rescuers at the risk of their own lives. By nightfall, the situation was desperate. The populace gathered along the river, many crying piteously. Without homes, clothing, or food, the residents were “tearing their hair, and on the verge of distraction.” They spent the night in the open amongst the ruins of their homes and businesses.

The next morning, officials froze the price of provisions and ordered flour from Philadelphia to prevent famine. They sent word to planters up and down the river instructing them to rush their rice, corn and peas to the city to be distributed from the King’s warehouses. Many victims gathered near the undamaged Governor’s House where Governor Miro dealt out bags of money to those most needy.

Five days later, the Cabildo began to make plans for rebuilding and soon initiated a long-running discussion about fire prevention. During the next few years, they acquired fire pumps, leather buckets, ladders and hooks. In 1793, Don Espiritu Liotau took charge of maintaining the fire engines and constructed a timber building to house them, itself claimed by fire only a year later.

Gradually, rebuilding progressed. Writing in April 1790, a local reported that the residents were making an effort to recover, but, he said, “It will nevertheless be a considerable time before the town again exhibits as elegant an appearance as formerly.”

In addition to a massive private rebuilding effort, work was proceeding on public structures, but there were no funds to build a new Cabildo, and the governing body was still meeting in temporary quarters when the city was struck by a second devastating fire on December 8, 1794. This one began on Royal Street in the mercantile center of town. Flames spread quickly, fueled by temporary huts erected after the first fire. The blaze reached almost to the new cathedral and devastated the valuable commercial section. Governor Carondelet reported that the financial loss was even greater than that suffered six years earlier, although fewer homes had been burned. Prisoners worked six fire pumps, but a low Mississippi River and empty private wells hampered their efforts.

Nearly a year after the fire, the city still lacked funds for building a civic structure, and Cabildo member Don Andres Almonester generously offered a construction loan. Using his own funds, Almonester was then building St. Louis Parish Church and the Presbytère, and he stipulated that the new Cabildo should replicate city engineer Gilberto Guillemard’s design for the Presbytère. Almonester’s intention was to make “the front of the Plaza uniform, which in fact would beautify it, as [the Cabildo and Presbytère] will form two equal wings to the Temple [St. Louis Parish Church].” Thus, the fires that destroyed a motley assortment of old buildings prompted the much-admired architectural composition fronting Jackson Square.

Beginning in 1795, the Cabildo enacted numerous building regulations that helped determine the appearance of today’s Vieux Carré. The elimination of flammable roofing materials made tile and slate prevalent in the town’s center. Early regulations limited frame construction, and one required the fronts of frame buildings to be of masonry or, at the least, covered with stucco. To reduce the spread of fires, another rule stated that “all houses, brick or frame, must precisely have their front facing the street.” Walled courtyards replaced front gardens and buildings were aligned precisely at the front of lots, creating a new urban form for the city.

Although enforced inconsistently, Spanish building regulations prevailed, and as the city moved to American control, safety-minded officials passed more building regulations and established fire-fighting mechanisms, not only in the Vieux Carré, but in the developing faubourgs. Fires continued to occur with regularity, but never again was the destruction as great as in 1788 and 1794. However tragic the loss at the time, the 18th-century fires prompted changes in the Vieux Carré that we enjoy today.