This story appeared in the May issue of the PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door monthly? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

Preserving the Recent Past 3, a gathering of preservationists sharing “the latest strategies for identifying, protecting and conserving significant structures and sites from the post-World War II era,” stretched over two action-packed days in mid-March on the University of Southern California’s campus in Los Angeles. Dating from the 1880s, the campus is a pleasingly harmonious blend of Romanesque Revival, Modern and Brutalist buildings, most ranging from two to four stories. The warm California sun shines brightly on the wide, manicured pathways linking the buildings, and a true “city within a city” feeling abounds.

It was the perfect setting for this year’s conference, which was preceded by two previous Preserving the Recent Past conferences, in 1995 and in 2000. In the 19 years since the last one, new technologies, new challenges and newly found appreciation for more recent architectural styles have developed. It was the overwhelming task of the PRP3 Organizing and Advisory Committees to choose the programming of the three focus tracks and to secure a keynote speaker guaranteed to thrill and inspire conference attendees. For the keynote speaker, they needed to look no further than world-renowned author, architect, historian and photographer Alan Hess.

The energetic, elbow-to-elbow crowd that filled Seeley G. Mudd Hall’s auditorium on the first day of the conference was practically buzzing as Hess took the floor. He is most widely known for authoring 20 books on Modern architecture, including Googie: Fifties Coffee Shop Architecture (1985), The Ranch House (2005) and Hollywood Modern: Houses of the Stars: Design, Style, Glamour (2018). Honestly, do you dare call yourself a Mid-Century Modern aficionado if Hess’ big, glossy The Ranch House isn’t front and center on your Noguchi coffee table?

Advertisement

During his beautifully presented slideshow, Hess asked attendees to consider the Cycles of Taste and their destructive impact on architecture. He spoke of Brutalism as the current battle. Despite being “strong, powerful, clear sorts of buildings, [found] all over the world,” they’ve fallen out of favor, and from the concrete, we have moved back to glass. Unpopular Brutalist buildings are facing alteration and demolition at ever increasing rates, despite burgeoning enthusiasm and appreciation, mainly driven by active social media users. Websites such as sosbrutalism.org and Instagram and Twitter, with hashtags like #SOSBrutalism, #brutalism and #brutalism_appreciation_society are being used by architects, preservationists and interested citizens to raise awareness of the importance of these buildings.

Searching #brutalism on Instagram recently returned more than 600,000 unique posts. Appreciation alone, however, does not save historic buildings.

How do we, as preservationists, community leaders and concerned citizens, disrupt the Cycle of Taste? Where an architectural style pushing 30 years of age is torn down and replaced with what’s “in” at the time, only to have that decision bemoaned and lamented 20 years after that?

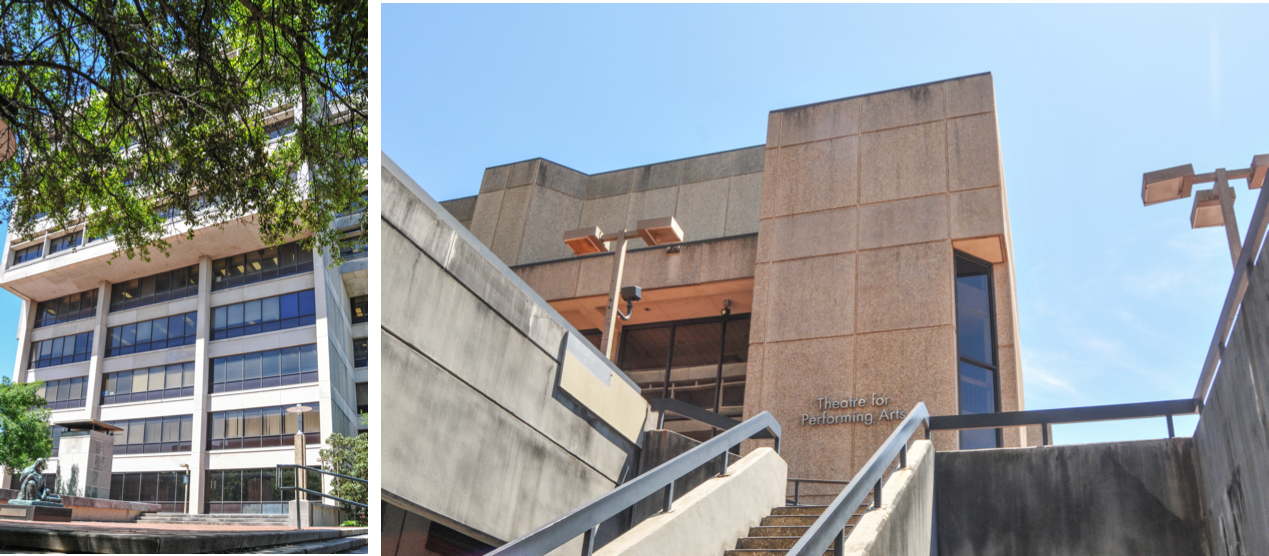

(Top left) Baton Rouge City Hall, built in 1978 and designed by Desmond-Miremont and Associates; (Top Right) Centroplex Theatre for Performing Arts, Baton Rouge, built in 1978 and designed by Desmond-Miremont and Associates; (Bottom left) The Riverfront Plaza, Baton Rouge, built in 1984 and designed by Lou Faxon; (Bottom right) Louisiana National Bank Building, Baton Rouge, built in 1968 and designed by Curtis and Davis. Photos by Alison F. Saunders.

Consider historic downtowns, where 1910s and 1920s Main Street-scale masonry buildings were slipcovered in metal, their facades obscured in the 1950s and ’60s, to look more like urban shopping malls and modern buildings seen along the interstate. In the 2000s and 2010s, revived interest in historic downtowns has led to the removal of the non-historic slipcovers. But the question arises now: are we removing slipcovers that (may) have gained significance in their own right?

Hess asked the question more directly: “How do we protect buildings that are not in current taste, that are out of fashion?” His advice was direct and action-based: Create a new narrative. Teach people what they should look for and appreciate, and how to appreciate it. Retain the good qualities of the buildings, master plans and sites, but acknowledge and find solutions to flaws. Incentivize research on unknown or under-appreciated architects of this time. Stay alert to the threats of demolition and deferred maintenance, and work towards capturing the public’s imagination and involvement in the retention of these resources.

After all, as Hess concluded, “the battle for the 1980s has just begun.”

After Hess’ keynote, conference attendees made their way to the first sessions within each track. Track A focused on History and Context; Track B was dedicated to Advocacy and Stewardship; and Track C explored Technical Conservation. It was impossible to attend sessions occurring simultaneously within each track, but making the tough choice of attending “Action Places: Sites Shaped by Social Issues and Movements,” “It’s What’s Inside that Counts: Conserving Postwar Interiors” or “Concrete Technologies: Advancing Repair and Conservation” was a great problem to have. In the months to come, we’ll review sessions within each of the tracks, focusing on architects, building styles, physical preservation strategies, theory, advocacy and history.

We’ll also explore how each of these topics directly relates to the preservation movement in Louisiana by answering these tough questions: How did chunky Middleton Hall wind up in the middle of Louisiana State University’s beautiful Italian Renaissance campus in Baton Rouge? What’s up with the Piazza d’Italia hiding behind the Lowes Hotel in New Orleans’ Central Business District? What does an exaggerated broken swan’s neck have to do with building construction? And even if you don’t appreciate Post-Modern architecture, why should we fight to save it? Stay tuned.

Alison F. Saunders is the Tax Incentives Director for the Louisiana Division of Historic Preservation.

Advertisements