This story appeared in the May issue of the PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door monthly? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

In a place with a penchant for anthropomorphizing houses, ascribing them names and sometimes gender and personality, the next logical step is to give them familial relations. Consider the “Thirteen Sisters” of Julia Street, the “Seven Sisters” (“Brides’ Row”) in the Garden District and the “Court of Two Sisters” on Royal Street, not to mention “Madame John’s Legacy” on Dumaine Street.

Perhaps the earliest buildings in New Orleans analogized to siblings (always female, it seems) were the Three Sisters of Rampart Street. Sadly, all three are “deceased,” their spaces now occupied by the parking lot at 228-238 North Rampart next to the New Orleans Athletic Club. But in their early years, the Three Sisters signaled a majestic new aesthetic in the Creole city, heralded by two of its most important architects, and for over a century, they gave a dignified air to what would become a rather gritty precinct.

It was the 1830s, and New Orleans was booming. The decade would see a doubling of its population, making the metropolis the third largest in the nation and the “queen” of the South. Being circumscribed by the narrow natural levee, and restrained from growing too far upriver or downriver for lack of urban transportation, developers made the best use of limited space, building higher and closer.

Rampart Street, the rear flank of the original city and barely populated in the 1700s, developed in the early 1800s as a working-class neighborhood of modest cottages with a large free people of color population, not unlike Faubourg Tremé across the street. By the 1830s, however, demand for urban space raised the value of even these back streets, and wealthier people had the wherewithal to build bigger townhouses. They wanted the latest look, and in this time and place, that meant Greek Revival. Among the idiom’s most enthusiastic American emissaries were James Gallier Sr., the brothers James and Charles Dakin, and Minard Lafever.

Advertisement

Testifying to the ascendancy of the Southern metropolis, the Dakin brothers and Gallier had recently abandoned New York City for greater opportunities in the New Orleans area, where, in various professional partnerships, the three architects would design a number of great buildings. Among the first commissions of the partnership of Gallier and James Dakin was on the corner of Rampart and Bienville streets. Gallier, an Irishman by birth who had Gallicized his birth name Gallagher, wrote of it in his 1864 autobiography: “While living in London, where every inch of building ground is turned to the best account, I had some experience in contriving to make the most of small spaces, and I now turned this knowledge to good advantage [in New Orleans]. There were three gentlemen who owned, among them, one lot of ground of no very great extent, and consulted me as to the best mode of improving it.”

The gentlemen were H.B. Cenas (who also happened to be the city’s notary public), J.R. Sterrett and James B. Hullin, and they respectively owned what would later be enumerated as 228, 232 and 236-238 North Rampart, the last situated on the corner of Bienville. Apparently the three men were associates, because they readily agreed upon a single vision. Gallier continued: “One of them said in a jocular way he should like three good houses built upon it. I took the hint, and made a plan for three houses, which appeared so feasible that they made a contract with me to build them, and when finished the owners expressed the highest satisfaction, and called them the ‘three sisters.'”

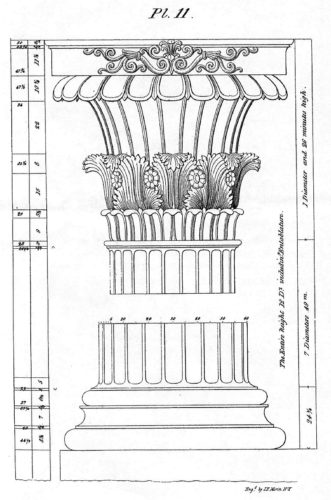

The Three Sisters’ facades included four Corinthian columns topped with unusual capitals upholding classical porticos, complete with Greek temple-like pediments and cornices. 1887 engraving by Eldridge Kingsley , courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection, Asccession No. 1957-4.

The original sketches, dated Dec. 20, 1834, and attributed to “Gallier & Dakin–architects” (Dakin being James), show three identical two-and-a-half-story, three-bay townhouses. Their facades are dominated by four Corinthian columns topped with highly articulated capitals (more on those later) upholding Classical porticoes, complete with Greek temple-like pediments and cornices. Whereas the two flanking units had square attic windows, the middle unit had an oval window, the sole structural distinction.

When viewed from Rampart Street, each unit’s parlor comprised the two bays on the left and a main entrance on the right, behind which was the side hall and staircase. Because the lots were not very deep (42 feet wide by 97 feet in length), the architects judged there was more space for lateral rather than rear dependencies. So they inserted three separate two-bay quarters to the right of each main house, each one set back a few feet and separated by a narrow alley. Their facades, strikingly ornate for slave or servants quarters, featured two square Corinthian columns with antefixa across the top. Of the three doorways tightly squeezed into each dependency, two went inside, and the third opened to an alley accessing the courtyard, pantry and cistern in the rear.

Most unusual was the architects’ plan to unify all three “sisters” with a single band-like entablature. Later photographs indicate only the two units closer to the corner were so fused, given the otherwise identical triplets an odd asymmetry, as if the Three Sisters weren’t all getting along. All three were, however, encircled by a heavy cast-iron fence, and had matching iron railings on their capacious balconies.

Advertisement

The buildings were erected in 1835, by which time Gallier and Dakin were busy working on a number of major commissions in both New Orleans and Mobile, Ala. At times James Dakin’s younger brother Charles would participate in the drafting, and it’s often unclear throughout the firm’s portfolio which principals ought to be viewed as the primary designer. (Dakin and Dakin would later form a partnership of their own, until Charles’ death in 1839.) As for the Three Sisters, design credit ought to go firstly to James Gallier and secondarily to James Dakin. Gallier’s quote uses the first-person singular, despite that he duly mentions the Dakins elsewhere in his autobiography.

Then there was Minard LaFever. Previously an employer of both Dakins and Gallier, LaFever became a premier agent in the spread of Classicism by sketching popular pattern books of Greek motifs, which abetted their replication and diffusion nationwide. LaFever and Gallier had previously formed an architectural partnership in New York City, where Gallier himself tried his hand at pattern-book publishing, producing the American Builder’s Price Book. It didn’t sell well, and that experience, combined with the mediocre New York architectural scene, is what drove Gallier to move to New Orleans.

LaFever played an indirect role in the design of the Three Sisters, or at least in one interesting detail. Those unusual capitals atop the Corinthian columns? According to architectural historian Arthur S. Marks, they were “the invention of Minard LaFever,” having appeared “in his Beauties of Modern Architecture (New York, 1835), a volume for which both Gallier and Charles Dakin had drawn plates when in his employ.” In Plate 11 of his pattern book, “LeFever retained the capital’s roundness, added a third register of leaves at the bottom, and introduced flowers between the acanthus leaves at the middle. Finally, at the top, the wholly abstracted waterleaves bend over and curl outward.” In his 2013 article in the Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Marks describes Gallier and Dakin’s Three Sisters in New Orleans as “frame two-story structures, their porticoed and pedimented façades…each supported by four giant columns that clearly derive from LeFever’s plate 11.” (See above left).

(Click image to view full size)

Architect Minard LaFever’s pattern book, Beauties of Modern Architecture (New York, 1835), featured this highly articulated capital design, which Gallier and Dakin incorporated into The Three Sisters. Image from Arthur S. Marks’ 2013 article in the Transactions of the American Philosophical Society.

Though by no means the first examples of Americanized Greek Revival architecture in New Orleans, the Three Sisters of Rampart Street were among the best and most prominent residential specimens, and were in the vanguard of the style’s diffusion from the Northeast to the lower South. Their visage on Rampart Street, with its unifying entablature and integral composition, was perfectly striking, looking something like a temple compound. The homes and their owners did well for decades.

Unfortunately, Rampart Street could not live up to the elegance of the Three Sisters. A vice district formed behind it in the 1850s and extended across Basin Street, where it flourished and eventually became the legal prostitution district known as Storyville (1898). The Three Sisters became storefronts with various tenement apartments upstairs, some decidedly seedy. When the corner unit at 238 North Rampart was raided in 1909, male tenants were convicted of “living off the earnings of women” (New Orleans Item, October 7, 1909). Upon Storyville’s closure in 1917, the iniquity moved directly onto North Rampart, which became known as the “Tango Belt,” an antecedent to today’s Bourbon Street, but with the sex, drugs and gambling of old Storyville. In 1918, a tenant of the 228 unit was arrested for dealing morphine and cocaine in hypodermic needles (New Orleans Item, April 29, 1918).

This being just off Canal Street, department-store warehouses and light industry also crowded the North Rampart scene, with the grungy Old Basin Canal and railroad tracks not too far away. Streetcars and auto traffic sped up and down North Rampart, and demand increased for parking. The Three Sisters became relics of a bygone age.

The corner unit at 238 North Rampart, last occupied by a hatter, was the first to be demolished, probably in the early 1930s. Next went the middle unit in 1945. The last surviving sister, 228 North Rampart, was deemed a “fire trap,” vacated in 1945, and razed around 1950. Its space was later occupied by an auto repair outlet.

Today all three are parking lots — a triple “death” of one of the city’s most outstanding architectural “families.”

And no one saved the capitals.

Richard Campanella is a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture and the author of “Cityscapes of New Orleans,” “Bourbon Street: A History,” “Bienville’s Dilemma” and other books. Campanella may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, or @nolacampanella on Twitter.

Left: This early 1900s image shows the Three Sisters of Rampart Street viewed from the Bienville Street intersection. All three units were demolished by 1950. Image courtesy of the New Orleans Public Library Louisiana Division and The Historic New Orleans Collection Vieux Carre Survey. Right: 228-238 Rampart today. Image from Google Maps.

Advertisements