This story appeared in the February issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

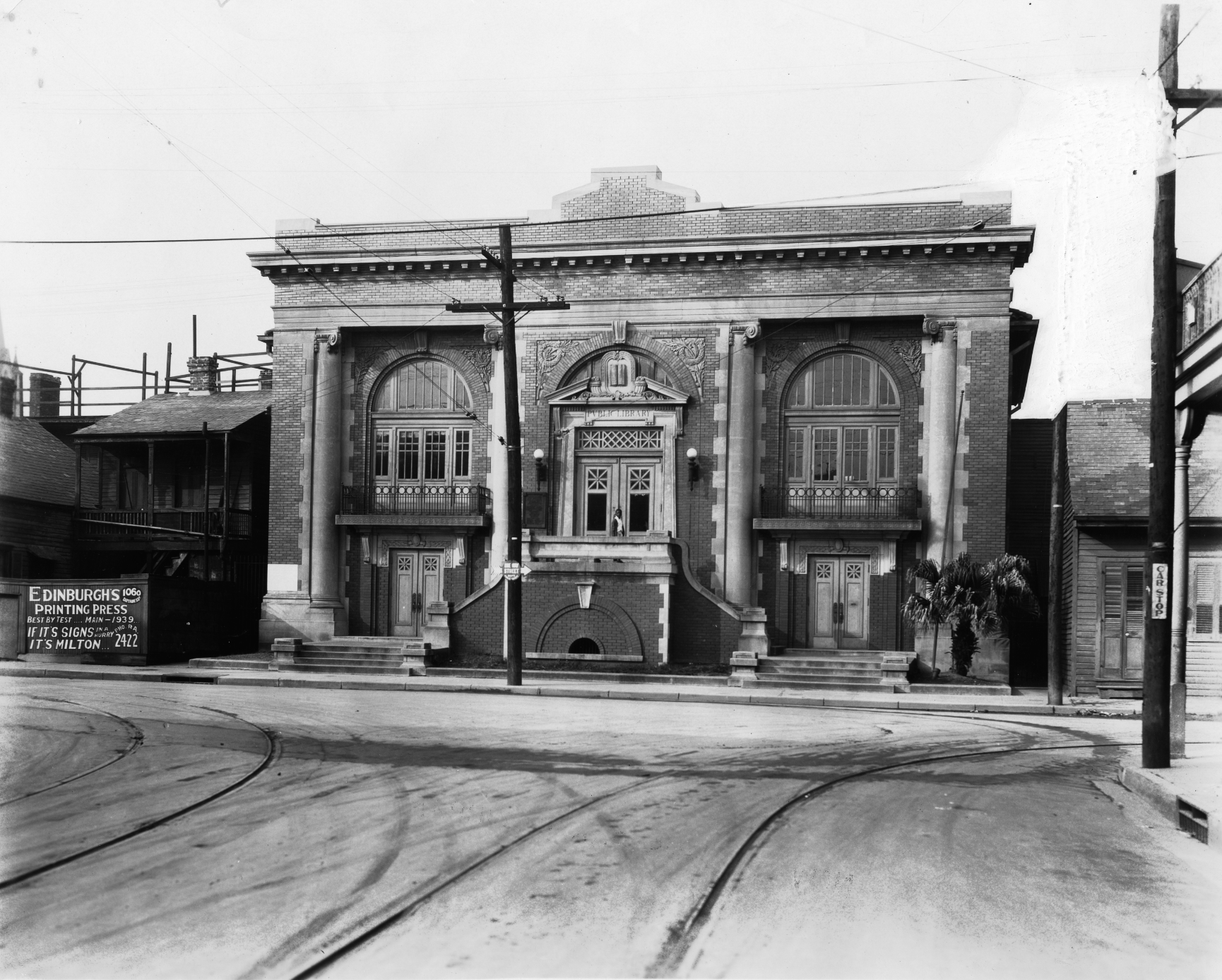

In October 1915, the City of New Orleans opened the Dryades Branch Library in Central City. A stately building, with a double staircase and second-level entrance, it would be the first — and for most of its existence, only — library open for African American patrons to borrow books in New Orleans.

Located within the Central City Historic District, which was added to the National Register in 1982, the Dryades library is the work of local architect William R. Burk, who designed the similar Canal Branch Library, which opened in 1911 in Mid-City. Burk’s other notable local commissions include Foto’s Folly Theatre in Algiers (built in 1915, now a church) and the Touro-Shakespeare Alms House (built in 1932, currently vacant).

The Dryades branch is not only architecturally significant in Central City — its design gives a sense of monumentality among the historic district’s mostly single-story homes — but also for its remarkable history serving as a community resource and gathering place during segregation. Last year, the building was nominated to the National Register of Historic Places as part of a class project with Tulane University Master’s of Preservation Studies program.

The nomination was presented to the Louisiana National Register Review Committee last summer. After revisions based on the committee’s feedback, an updated nomination form was submitted to the National Register Office of the National Parks Service, which approved the listing in October.

Advertisement

Recogition on the National Register highlights the Dryades library’s historical importance in the city. Funds for the construction of the library came from steel magnate and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, who aided in the development of 1,689 American libraries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

City neglect of the Dryades branch was unfortunately a pattern that developed almost immediately. Funding data from its opening through the early 1930s showed that the branch consistently received the lowest disbursements from the city. In 1925, other city libraries added an average of 1,100 new books to their collections, while the Dryades branch only added 448.

Despite this, yearly reports indicate that the building was consistently well maintained, and for many years, Dryades was the only city library open on Sundays, offering more hours than any of the other branches. The building’s auditorium space was used by the community for gatherings and events, including regular meetings of the NAACP and numerous Works Progress Administration classes. Efforts were made by the community to include books by African American authors in the library’s collection.

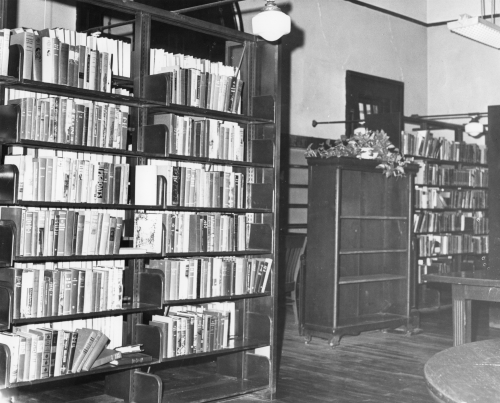

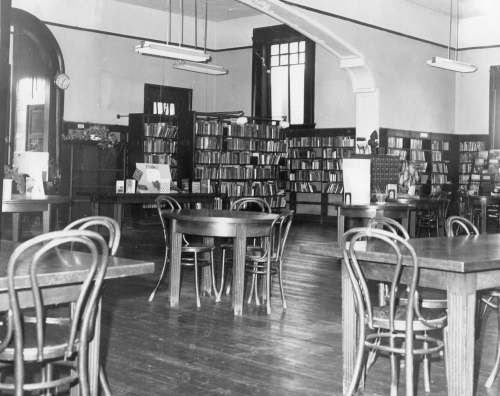

Interior shots of the library taken in 1964. Photos courtesy of the City Archives & Special Collections, New Orleans Public Library.

The Dryades branch is the only remaining library building that served the New Orleans African American population during segregation. New Orleans public libraries were integrated in 1954. In anticipation of the Brown vs. The Board of Education decision, which would mandate the desegregation of public schools and overturn the precedent of “separate but equal” facilities, the New Orleans Library Board worked swiftly to apply these principles to the public libraries. Critical to this push were Rosa E. Keller, a longtime board member who advocated to integrate the libraries, and Albert Dent, the president of Dillard University who organized community members to lobby the board.

When being considered for the National Register, a property must demonstrate significance according to at least one of four criteria. In the case of the Dryades Branch Library, the structure falls under criteria “A” in that it “is associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history.”

Forming an argument for the building’s nomination to the National Register required demonstrating its significance in the areas of Education and Ethnic Heritage during the period in which it operated as a library. An extensive history of the building exists in the form of monthly reports and board meeting minutes, held in the Louisiana Division of the New Orleans Public Library Archives. These records, supported by historic newspapers and property records, served as the primary source in the writing of the library’s narrative history.

Advertisement

While the library’s future was uncertain for a number of years as circulation declined through the early 1960s, it was damage caused by Hurricane Betsey in 1965 that ultimately led to its closure. In 1966, the city sold the building, and it was renovated for use as a hotel. It operated as such for the next several years, until it was purchased in 1979 by the New Orleans Youth Foundation.

The majority of alterations to the structure have been to the interior, most significantly the walling off of the interior staircases and the division of the rear section of the upper level into offices. The distinctive façade is largely unchanged, and features an elaborate entrance decorated with an open book, serving as a visual reminder of the building’s history.

The building is now part of the Dryades YMCA, and is used as a band room and cafeteria for the nearby James M. Singleton Charter School. The YMCA hopes to make improvements to the space in the near future and continues to use it to serve the community.

The building that once housed Dryades Library is now part of the Dryades YMCA. Photo by Liz Jurey.

While it no longer operates as a library, the building’s use through the YMCA is not far from its original function. Proximity to the YMCA was noted as a reason for the original selection of the site in 1913, and the space has a long history of providing services to the residents of Central City.

The importance of the library was noted by Anita L. Johnson, who served as a librarian at the Dryades Branch Library for more than 30 years. In her 1941 annual report, Johnson wrote, “Many borrowers expressed gratitude at the assistance gotten from the library. Many expressed that they would not be able to get along were it not for the library. These remarks are very gratifying. Each year the library is serving the community in a larger way.”

Advertisements