This story appeared in the February issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

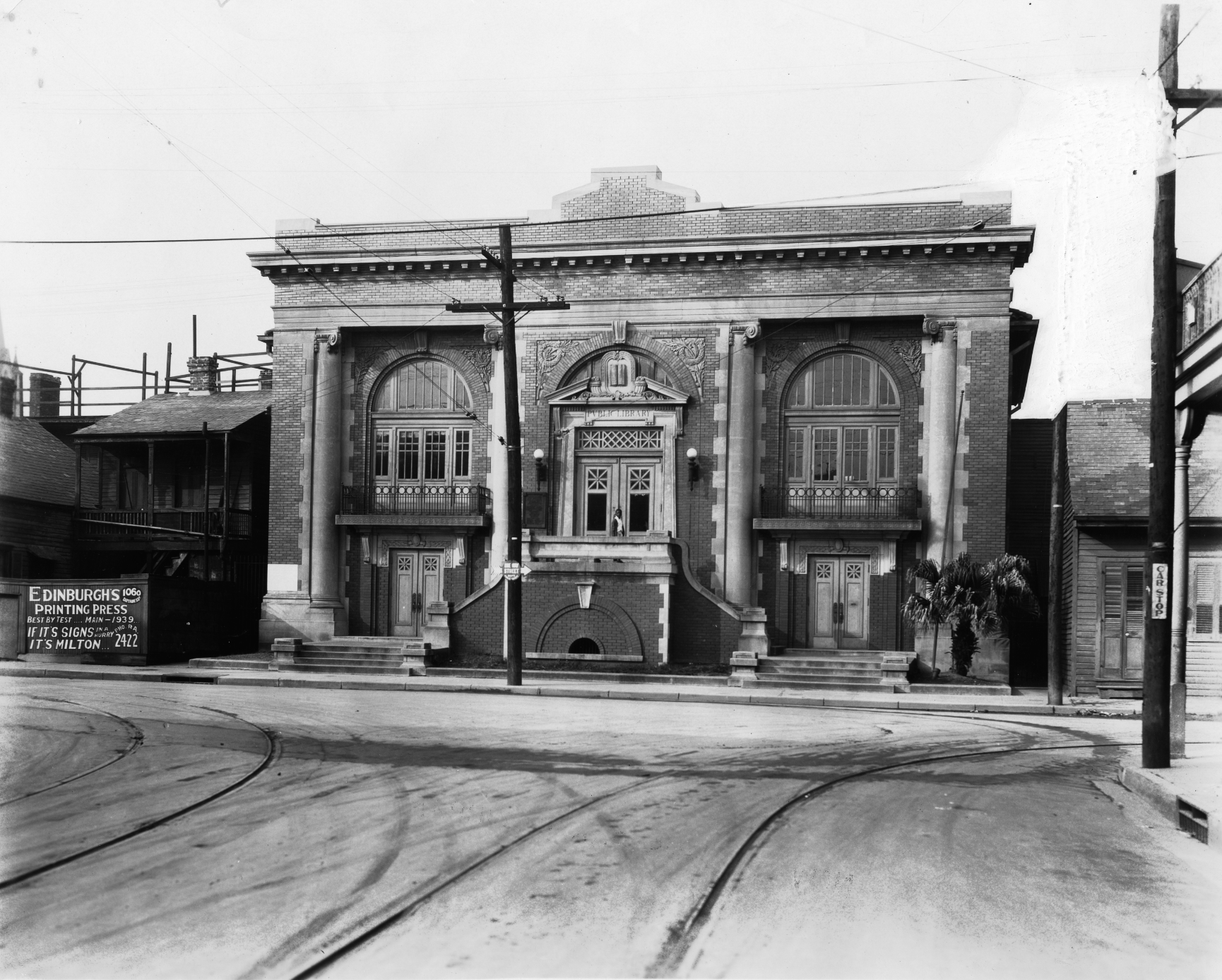

The tall columns and Greek Revival details of Evergreen Plantation are eye-catching to motorists traveling down River Road in Edgard, La. Not immediately visible from the road, though, is a collection of buildings that give a deeper, more complete view of the site’s history. Slave cabins from the early 19th century stretch behind the main house in two rows beneath a canopy of ancient live oaks and Spanish moss.

A new initiative by the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training (NCPTT) is using modern laser scanning technology to document historic sites, like this one, and others across the country associated with slavery and tenant farming. The project will help bring the histories of the people who once lived and worked on these sites to the forefront, making them digitally accessible as an educational tool.

Founded in 1994 and based in Natchitoches, NCPTT is the U.S. National Park Service’s technology-based research and training center. Its new Slave and Tenant Cabin Documentation Project was launched in October 2020 and has started site documentation in Louisiana before traveling to other locations throughout the country. The traveling team includes NCPTT’s chief of technical services Jason Church, project supervisor; research associates Ina Sthapit and Sreya Chakraborty, who operate the laser scanner and create 3D models; and videographer Isabella Jones, who collects oral histories at each site and creates videos to share the information with the public.

“We’re always looking for more sites, and a lot of interest has been through social media,” Church said. “We have a really active Instagram, and we’re trying to post every day that we’re documenting. People have emailed and called us and said, ‘I heard your podcast, I saw your Instagram, and I’ve got a site, would you like to come see it?’ And the answer is always yes.”

From nonprofit and government-run heritage sites to privately owned farmland, a wide variety of sites have reached out to NCPTT to contribute to the laser scanning and documentation project that will help to tell a fuller American history about slavery and tenant farming.

Photo 1: Evergreen Planation’s 22 extant slave cabins from the early 19th century are preserved and maintained on their original site, with two rows stretching behind the main house beneath a canopy of live oak trees. Photo 2: Artifacts inside one of the slave cabins is used for site interpretation and education. Photos by Liz Jurey.

Advertisement

LASER SCANNING

On a sunny day in January, a small group of NCPTT staffers gathered in front of one of Evergreen Plantation’s slave cabins and hovered around a FARO focus laser scanner, a small tripod-mounted device which rotated and emitted several beeps while collecting millions of data points to translate the historic building into a 3D model.

“It throws out a beam of light, takes information back, and captures it like a photograph,” Sthapit said. “That’s what we process in the software to make a 3D virtual model that can be seen by everyone.”

The laser scanner detects surfaces, but it can’t scan through a building’s walls like an x-ray. Working around each building, the team sets up the laser scanner from multiple angles to capture every surface on the exterior as a “point cloud” of data, and then repeats the process inside the building. After multiple scans are taken, the team uses software to process the individual scans and stitch them into a complete model.

“We have been working on this site for two weeks, and we have finished documenting 16 cabins out of 22,” Chakraborty said. “We take about eight to nine scans on average on the exteriors, and then we move to the interiors. On average, we do about 15 scans, which takes about two and a half to three hours for each cabin.”

After creating the 3D models, the team uploads them to an online platform called Sketchfab, which allows users to view and move around the scanned scene in three dimensions. On that platform, tech-savvy users with virtual reality headsets can even connect their VR equipment to their phones or computers to virtually experience the space. Walk-throughs of the virtual models and videos of oral histories will be posted on NCPTT’s Youtube, Instagram and Facebook profiles. Eventually, all of the scanned sites will be cataloged on an Esri StoryMap, with a pinpoint for every site with links to photographs, models and oral histories.

“The idea is really to show what’s out there and to reach as many people as possible with the knowledge that we have at our hands,” Chakraborty said.

RACING AGAINST TIME

A historic site like Evergreen Plantation, with 22 slave cabins preserved and maintained on their original sites, is an exception to the typical conditions facing these types of dwellings. Rural slave cabins — and later tenant farming cabins — were once prevalent throughout the South but are becoming increasingly rare as time marches forward and less interest was shown in preserving their history. After years and years of disuse, many of these buildings have eventually been lost to deterioration by the elements or demolished by landowners to make way for additional crop cultivation.

“We’re racing against time to try to capture these,” Church said. “For example, a cabin that Ina scanned early on was scanned on a Tuesday, and then on Thursday it collapsed.”

Collecting oral histories for the project is also of timely importance. After emancipation, the institution of chattel slavery morphed into sharecropping and tenant farming: a form of economic slavery. The tenant farming system was still in existence in Louisiana until the mid-20th century when agriculture became widely mechanized and industrialized. With the last generation of people connected to that period of history growing older, the NCPTT hopes to collect as many firsthand accounts as possible.

Some of the slave cabins at Evergreen Plantation were inhabited until the 1940s. Other similar cabins around the state were occupied by tenant farmers until as recently as the 1960s and 1970s.

“I talk to people who grew up or lived in these cabins on different plantations,” Jones said. “Getting that firsthand story of, ‘This is what this exact cabin was like; this is what I lived through; this is what I experienced,’ and being able to share those stories that otherwise wouldn’t be heard makes it more real.”

While the team was on site at Evergreen Plantation, Jones interviewed Ingrid Green, a local poet and author whose mother and grandmother were born at Destrehan Plantation.

Photo 1: NCPTT research associates Ina Sthapit and Sreya Chakraborty assemble targets and use a FARO focus laser scanner to take a 3D scan of a slave cabin. Photo 2: Videographer Isabella Jones gives Preservation in Print staff a look at the Evergreen Plantation site where NCPTT is collecting oral histories and 3D laser scans. Photos by Liz Jurey.

Advertisement

VIRTUAL CONNECTIONS

The world has become increasingly virtual during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the virtual models of the sites documented by NCPTT can be used as an educational tool to safely bring history into the homes of people around the world.

At Evergreen Plantation, the laser scans of the 22 slave cabins and oral histories collected by the NCPTT team will add to ongoing research and interpretation efforts to tell the stories of the enslaved individuals on the plantation. Evergreen’s slavery database — available online at evergreenplantation.org — contains a collection of primary source documents, providing names and details about their lives. The Ancestor Project, also available on the website, highlights the stories of some of the individuals with biographies, images, narratives and primary source documents.

“We’re certainly grateful to (NCPTT) for coming out here. It’s wonderful that they have focused on both the architectural aspects and the human element of stories, and combined the two to give a broader, more full picture of the importance of these structures,” said Katy Morlas Shannon, head of history and interpretation at Evergreen Plantation. “It’s one more step in visualizing and imagining, and building empathy and understanding of the experience.”

The nationwide documentation project is ambitious, but the NCPTT team is excited to undertake the important work. “You get to go to sites, you get to experience histories so closely that are highly underrepresented,” Chakraborty said.

“Exploring the places and unraveling the history has been the most rewarding part for me, because every new place that we go has a new history or a story behind why the place is there,” Sthapit said.

As the project unfolds, there are several ways to follow along with the team, see the 3D scans and listen to the oral histories:

- Instagram: @ncptt.nps

- Facebook: facebook.com/ncptt

- Sketchfab: sketchfab.com/ncptt_nps

- Youtube: youtube.com/ncptt

“If anybody has a grandmother who wants to talk to us, we want to talk to them. We want everybody’s story,” Church said. “If you were living in these cabins and working in the fields or living in them when it was a neighborhood and did other things, those are the stories we’re still looking for.”

Do you have a historic slave cabin or tenant farmer dwelling that you’d like the NCPTT to document and laser scan for this project? Would you or someone you know like to be interviewed for an oral history? Contact Jason Church at jason_church@contractor.nps.gov. Interviews can be conducted remotely.

After capturing multiple scans from several angles around and inside a cabin, the NCPTT team uses software to stitch the individual scans into a complete 3D model. Image courtesy of NCPTT.

Davis “Dee” Allen is PRC’s Communications Associate and a staff writer for Preservation in Print.

Advertisements