Above image by Chris Granger

This story appeared in the August/September issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

On a balmy June day on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, architectural history buffs and preservationists headed to Ocean Springs, Miss., to get a glimpse inside the Charnley-Norwood House. Designed by influential architect Louis Sullivan in 1890 and now owned by the State of Mississippi, the site is typically open to visitors by appointment only, but a special event organized by the Mississippi Gulf Coast National Heritage Area offered an open house to celebrate the 156th birthday of architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

Walking through the restored house’s light-filled pine interiors with tour guides, visitors could easily see how its design and use of native materials worked in harmony with its natural surroundings to inspire Wright — a young draftsman in Sullivan’s office at the time — and laid the foundation for the superstar architect’s early career.

All along the Mississippi gulf coast are other surprising historic treasures like the Charnley-Norwood House. On the drive from New Orleans to Ocean Springs, the scenic ride down Highway 90 revealed a picturesque landscape dotted with hidden gems, historic architecture, small towns and bustling beachfronts. The Mississippi coast has long been a favorite respite for New Orleanians’ quick getaways because of its proximity and its sunny beaches, but the historic communities nestled along the waterfront have much more to offer to residents and visitors alike.

Thriving Main Streets with award-winning restaurants and unique mom-and-pop retailers sit at the center of friendly neighborhoods and picturesque historic homes. World-renowned museums, cultural institutions and fascinating historic sites offer a look into the history and culture of the state’s 62-mile coastline. Communities once devastated by storm damage have rebuilt and bounced back stronger than ever, and preservation projects have continued throughout the region as business owners, homebuyers and nonprofit organizations find new inspiration in Mississippi’s historic buildings.

The following list of sites can help preservationists plan a quick road trip along the Mississippi coast. During your trip, make sure to leave room in your travel plans to explore other unique places off the beaten path at the coast’s vibrant, historic downtowns.

Interactive map not displaying properly? Click here to open in a new window, or scroll below for a plain-text version of the story.

303 Union Street, Bay St. Louis

Built in 1922 by the One Hundred Members’ Debating Benevolent Association, the 100 Men Hall has been a center for African American social life in Bay St. Louis for more than a century and is still operating as a music venue and event space today. The organization was one of the many benevolent associations common throughout the South during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The associations sought to bolster the social, economic and political power of African Americans while providing members with medical and burial benefits at a time when insurance agencies discriminated against people of color.

In its heyday, the 100 Men D.B.A. Hall hosted events and live performances with some of the most legendary musicians of the time — including Muddy Waters, Ray Charles and Fats Domino to name a few — and became a stop on the “Chitlin Circuit,” a network of venues that welcomed Black performers during Jim Crow-era segregation.

The benevolent association closed the hall’s doors in 1982, and the building was nearly razed after sustaining damage during Hurricane Katrina, but consecutive owners restored the building and breathed new life back into the space. The vernacular Craftsman building’s historic details include exposed rafter tails, wood clapboard siding, wood casement windows and a metal roof.

The venue is also one of the few extant landmarks on the Mississippi Blues Trail. Throughout the state, blue historic markers detail the history of people and sites that shaped American music. The “Blues Trail” iPhone app is available to download for free to explore all of the sites.

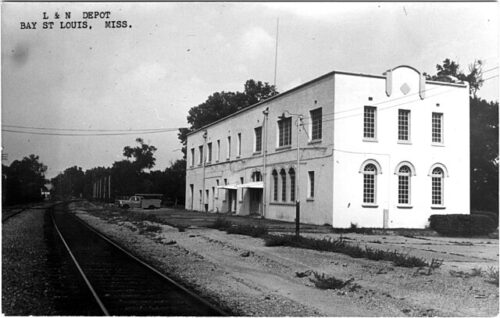

1928 Depot Way, Bay St. Louis

Present-day photo by Dee Allen, historic photo courtesy of Wikicommons

The ornate Mission Revival-style L & N Train Depot was built in 1928 to replace Bay St. Louis’ previous Queen Anne-style train station that was destroyed in a fire. After years of abandonment, the depot was restored in 1996 and its stucco-clad facade now highlights ogee arches, Solomonic columns, quatrefoils and other decorative trim in a bright red-orange paint. A free museum and visitors center is located inside the building today, with exhibits about the history of Bay St. Louis, Carnival costumes and memorabilia, and the work of folk artist Alice Moseley.

Passenger rail has not serviced the station since Amtrak ended operations following Hurricane Katrina, but service could soon be restored between New Orleans and Mobile, Ala., with additional stops along the Mississippi Coast. If the ongoing infrastructure project moves forward as planned, New Orleanians could soon board trains at Union Passenger Terminal for day trips to Bay St. Louis, Gulfport, Biloxi or Pascagoula.

9439 Creosote Road, Gulfport

At the northern edge of Gulfport in Turkey Creek — a freedmen’s community established by emancipated African Americans during the Reconstruction era — the Phoenix Naval Stores building is the last remaining structure of the former Yaryan/Phoenix Naval Stores Company and a vestige of the timber industry that once proliferated throughout the region. The industrial site was a major employer for the residents of Turkey Creek and manufactured turpentine, creosote and other pine sap derivatives.

An industrial explosion killed 11 workers at the plant in 1943, and the former paymaster’s office building survived the disaster due to its fireproof construction. The structure was then moved 1,000 feet from its original site and converted into a residential building. When the company closed its doors the following decade, the remaining buildings on the site were demolished.

The structure became abandoned in the 1990s, and the site was featured on the Mississippi Heritage Trust’s “10 Most Endangered Historic Places” list several times. The historic building was restored in 2021 with the help of the National Park Service’s African American Civil Rights Grant Program. Its interiors and front porch were rebuilt and restored, and separate front door entrances serve as a reminder of Jim Crow-era segregation. The site is now home to the Yaryan-Phoenix Naval Stores Museum and Turkey Creek Community Initiatives. Visitation is available by appointment only.

Ship Island, Gulf Islands National Seashore (Ferry departs from Gulfport Harbor.)

Adventurous visitors can take a one-hour ferry ride from Gulfport to Ship Island, 12 miles off the coast, to visit the historic military fort at the Gulf Islands National Seashore and enjoy a day at the beach.

Completed in 1866, the fort is one of the last “Third System” forts constructed in the United States in the early-to-mid-19th century. The network of 42 masonry forts included Fort Pike, Fort Macomb and Fort Proctor in the New Orleans area, and were built as the third phase of the country’s defense policy to protect the nation’s most valuable ports.

Construction on Fort Massachusetts began in 1859, and the unfinished federal fort was seized by Confederate forces in 1861 shortly after Mississippi seceded from the Union. Federal troops regained control of the fort several months later and used the site as a staging area for the recapture of New Orleans in 1862.

Later during the war, the fort was home to the Second Louisiana Native Guard, a Union regiment of free men of color organized in New Orleans. The guard was one of the first regiments with non-white officers in its ranks and one of the first predominantly Black regiments to engage in combat with Confederate troops. At Ship Island, the unit practiced military drills, constructed artillery batteries around the unfinished fort, and guarded Confederate prisoners of war.

Today, the site is operated by the National Park Service, and rangers and volunteers give free guided tours of Fort Massachusetts during the spring, summer and fall.

1166 Irish Hill Drive, Biloxi

Photo courtesy of The Library of Congress

Photo courtesy of The Library of Congress

The city-owned and city-maintained historic cemetery in Biloxi is a testament to the community’s centuries-old history, with tombstones and ornate mausoleums dating from the early 19th century to the present day. The cemetery’s oldest section sits along Beach Boulevard and overlooks the Gulf of Mexico, while more modern burial sites stretch further to the north. Decorative cast-iron fences and historic Live Oak trees strewn in Spanish Moss enhance the landscape.

The Preserve Biloxi Committee hosts an annual Old Biloxi Cemetery Tour in the fall and has created self-guided cemetery tours that tell the stories of the historic figures buried there. The tours earned a Heritage Award for Excellence in Preservation Education from the Mississippi Heritage Trust. To learn more, visit discover.biloxi.ms.us/old-biloxi-cemetery-tour

1050 Beach Boulevard, Biloxi

Photos courtesy of The Library of Congress

Photos courtesy of The Library of Congress

Biloxi’s historic lighthouse is one of the most prominent landmarks along Mississippi’s coast. The structure was engineered in Baltimore and assembled in Biloxi in 1848, making it the first cast-iron lighthouse built in the South.

Until the Coast Guard took over operations in 1939, the lighthouse was operated by civilians — many of whom were female — including Maria Younghans, who had the longest tenure as the keeper of the lighthouse from 1867 to 1919. The light was deeded to the city of Biloxi in 1968 and was opened for public tours afterwards.

The lighthouse stands at 61 feet tall and is capped with a cast-iron dome and weathervane. Visitors to the site can climb the narrow 57-step spiral staircase and a ladder up to the light cupola at the top for a panoramic view of the gulf. Tours are offered every day at 9 a.m.

510 Washington Avenue, Ocean Springs

Photo courtesy of The Library of Congress

Photo courtesy of The Library of Congress

Located in historic downtown Ocean Springs, the Walter Anderson Museum of Art opened in 1991 to celebrate the work of one of the Gulf Coast’s most well-known visual artists.

Anderson was born in New Orleans in 1903 and is most known for his vibrant paintings and intricate woodblock prints that expressed the beauty of the Mississippi Gulf Coast, where the artist lived for most of his years until his death in 1965.

The museum building itself is not historic, but the collection’s crowning jewel is the artist’s “Little Room”— a floor-to-ceiling depiction of the transition from day to night on Mississippi’s Horn Island — which the artist created in the nearby Greek Revival cottage where he spent the later years of his life. The mural was discovered after the artist’s death on the walls and ceilings of a 1939 addition to the cottage, and the entire room was relocated to the museum in 1991.

509 East Beach Drive, Ocean Springs

In 1890, influential Chicago-based architect Louis Sullivan visited the Gulf Coast and decided to purchase a waterfront property in Ocean Springs. He designed two adjacent vacation homes: one for himself and one for his friends James and Helen Charnley.

Sullivan was well-known for his influence on early skyscraper designs, but the two beach houses he designed in Ocean Springs followed the architect’s famous “form follows function” philosophy with simple horizontal-oriented designs that differed from most other Victorian-era architecture of the time. The homes’ use of materials that were harmonious with the natural surroundings were inspiring to the early career of architect Frank Lloyd Wright, who worked under Sullivan as a draftsman on the project.

The Charnley home was sold to the Norwood family in 1896, and the home was destroyed by a fire the following year, but it was quickly rebuilt with Sullivan again serving as the architect.

Hurricane Katrina destroyed Sullivan’s former home in 2005, and the Charnley-Norwood House next door was heavily damaged. The State of Mississippi purchased the architecturally significant structure in 2011 and embarked on an extensive restoration. The site is now open to the public by appointment only; visit msgulfcoastheritage.ms.gov to learn more.

4602 Fort Street, Pascagoula

Present-day photo courtesy of The Library of Congress, c.1941 photo courtesy of Wikicommons

Built during the French Colonial era, the LaPointe-Krebs House was recently dated to 1757 through a dendrochronological study performed by the University of Southern Mississippi. Predating the American Revolution, the building is the oldest extant building in the state of Mississippi and a rare example of French Colonial architecture still standing on the Gulf Coast.

The building was constructed partially with tabby walls, a concrete-like material made with oyster shells. Other wall sections used the poteaux-sur-sole (post on sill) timber framing method, with bousillage (a mixture of clay and Spanish moss) filling the spaces between timbers. The site is also an important Native American archaeological site, with excavations revealing many artifacts from the Pascagoula Indians who inhabited the site before European colonization.

The historic site had been heavily damaged by hurricanes and termites, but a meticulous restoration returned the site to its former grandeur and earned a Heritage Award of Excellence for Rehabilitation from the Mississippi Heritage Trust in 2022. The house and adjacent museum are once again open to visitors.

Dee Allen is PRC’s Communications Associate and a staff writer for Preservation in Print.