This story appeared in the December/January issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

Remember the Robért’s on Annunciation Street, and the Schwegmann’s before it? Vacant for years following Hurricane Katrina, the former supermarket building had been demolished in 2018 for a new apartment complex and parking garage, not unlike the Saulet Apartments built nearby in 2000.

Centuries before the site (1321 Annunciation St.) hosted supermarkets, the property stood salient from its surroundings, as home to an early Spanish colonial plantation house, and later an elegant Neoclassical mansion used as a private school and hospital.

What triggered its development was the deteriorating relationship between the French monarchy and the Society of Jesus, the religious order known as the Jesuits, in the 1760s. The Crown viewed the international Jesuits as a threat to its authority, and in 1763, it expelled the priests from the French Empire, including Louisiana — even as France prepared to transfer control of that colony to the Spanish.

Authorities confiscated the vast Jesuit plantation, which the Society had purchased starting in 1726 from New Orleans founder Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, and by 1763, it spanned from present-day Common Street to Felicity Street. When Spanish officials — themselves no friends of the Jesuits — fully took control of Louisiana in 1769, they proceeded to sell the seized land to private parties.

What is now the Central Business District came mostly into the possession of the Gravier family, and the remainder, roughly from present-day St. Joseph Street up to Felicity Street, got divvied into four plantations sold to the families Delord-Sarpy (later transferred to the Duplantier family), Saulet, Robin and Livaudais.

The four families established agricultural enterprises on their respective parcels, each of which measured six to eight arpents of frontage along the Camino Real (the Royal Road — that is, Tchoupitoulas Street, or the Road to the Chapitoulas Coast) and extending 40 or more arpents back to the swamp. Each family erected a plantation house and ancillary buildings, including dependencies for enslaved work forces, toward the front of their parcel. Locals referred generally to the area as the upper banlieue, meaning the upriver outskirts of the city.

It was the plantation house of the Saulet family that, 200 years later, would become space for a Schwegmann’s.

Photo 1: St. Simeon Select School, circa 1906. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress. Photo 2: 1922 Army Air Corps scene showing Saulet House at the upper right. Photo courtesy of Richard Campanella.

Thomas Saulet (often spelled Solet) purchased this property in 1763 from Joseph Petit, who, according to architectural historian Samuel Wilson Jr., had bought it two days earlier — an early “flipper” — at the Spanish government sale of the Jesuit confiscation. Around 1765, Saulet erected, according to two archival documents cited by Wilson, “a master house constructed of colombage…with front and rear gallery [and] all the dependent buildings,” including “a kitchen, a storehouse, [and] considerable lodgings for the Negroes and other servitudes.” The house contained six rooms on the main raised floor and probably resembled other Creole country houses of this era, with a double-pitched hipped roof, central chimneys and an airy gallery.

The house did not abut Tchoupitoulas Street, but rather sat back 800 feet or so, giving it space for gardens away from riverfront bustle. Nor did it align squarely with present-day Annunciation Street, which of course did not exist at the time.

In April 1788, following the Good Friday Fire that destroyed most of New Orleans proper, the Gravier family had their plantation subdivided by surveyor Carlos Trudeau to become the Suburbio Santa Maria (Faubourg Ste. Marie). As New Orleans’ first suburb, the new street layout initiated a plantation-to-faubourg transformation that would continue for a century to come, turning croplands into cityscapes one arpent at a time.

Bernard Marigny did as much on his plantation below the city in 1805, when he hired Barthélemy Lafon to create the first of the downriver suburbs, the Faubourg Marigny. Others followed farther down the lower banlieue.

From 1806 to 1810, all four of the upper-banlieue families — Duplantier, Saulet, Robin and Livaudais — decided to do the same. Their disparate properties would become unified under an ambitious Classical plan also designed by Lafon, putting the French-born ingénieur géographe in the unusual position of expanding New Orleans at both ends around the same time. Replete with playful Greek toponyms, Lafon’s design had elements of a Grand Manner Plan, with angles and diagonals deployed to incise gridded streets along a curving riverfront upon a widened natural levee. Lafon also made space for an amphitheater (hence Coliseum Square), an academy or prytaneum (hence Prytania Street), public markets (hence Market Street and the later Dryades Market), parks (Annunciation Square and Tivoli Circle, now Harmony), and a fine stormwater management system.

What resulted were the Faubourg Duplantier, Faubourg Saulet, Faubourg La Course (named for its racetrack — hence Race Street), and Faubourg Livaudais. We now call this area the Lower Garden District, a term coined by Sam Wilson in the early 1960s.

By now nearly 50 years old, Thomas Saulet’s former plantation house found itself on Annunciation Street, two squares in from Tchoupitoulas, and its surrounding grounds landed on the market as streetside parcels. Scores of newspaper ads in French and English during subsequent decades advertised lots for sale in the “Fauxbourg Saulet,” as banlieue gradually became faubourg.

After Saulet died in 1817 and his widow followed in 1823, her son François Saulet became the titleholder to the lot with the circa-1765 house. Around 1832, he had the old house demolished and replaced with a large square brick mansion more redolent of American stylistic sensibilities, with a center hall and Doric columns and a balustrade around its nearly flat (very non-Creole) terrace roof. People called it the Saulet Plantation House, despite that, unlike its precursor, this residence was more of a villa or gardened mansion, with no agricultural function.

Writing in the New Orleans States in 1953, Wilson described the circa-1832 Saulet House as “an example of that transitional style when the architecture of the so-called Federal or Early Republican period was merging with the newer style of Greek Revival.” He noted its similarity to the Zeringue family’s famous Seven Oaks Plantation House in Westwego, pointing out that the interior staircases were “exactly the same arrangement as is found in the Zeringue house… [B]oth may well have been the work of the same unknown architect.” (Seven Oaks, built around 1840, would fall to bulldozers in 1977.)

By 1850, the surrounding neighborhoods had become fully urbanized, and the riverfront area across Tchoupitoulas buzzed with cotton presses and port industry. No longer was Annunciation Street a leafy setting for a country villa. After François Saulet died, the property was sold in 1859 to James and Philip Rotchford, who the next year sold it to the Sisters of Charity (Daughters of Charity). Other members of the Saulet family, however, continued to live nearby.

The nuns had in mind a more apropos use for the big house in an affluent urban neighborhood: a finishing school, known as St. Simeon’s Select, for girls and young ladies. By the late 1870s, eleven teachers were educating 170 pupils in the former Saulet House, while another 260 students took classes in the affiliated St. Vincent’s School, which filled half the block bounded by Annunciation, Thalia, Constance and Melpomone streets. A photograph taken around 1906 shows the circa-1832 main structure of St. Simeon’s Select School in excellent condition, backed by a chapel, surrounded by horticulture, and fronted by a dozen schoolboys, clinging to the cast-iron fence and hamming for the camera.

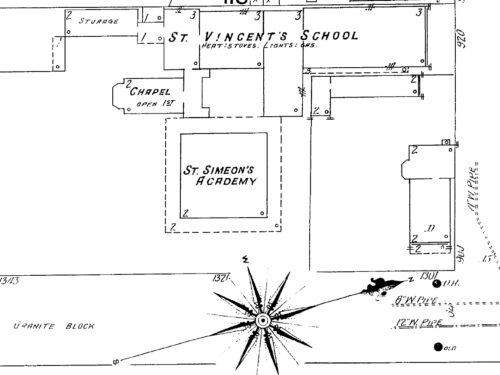

Photo 1: Barthélemy Lafon’s street grid overlaid on original Saulet plantation lines, from 1815 Tanesse Map. Photo 2: Former Saulet House, shown as St. Simeon Academy in the 1909 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map.

When St. Simeon’s closed in 1912, the nearby parish church of St. Teresa’s of Avila used the complex for its parochial school, though it remained in the ownership of the Sisters of Charity. In 1922, the nuns sold it to the Sanitarium Company for use as a private mental institution named St. Luke’s. The next year, a descendent of the original owners, Leona Saulet, bought back her ancestral home, and in 1924, she presented it to the Sisters of Mercy for use as an infirmary dedicated to her late husband. For the next 30 years, New Orleanians would know the Saulet House, surrounded by ward wings built in the late 1920s, as the Leonce M. Soniat Memorial Mercy Hospital. “The old Saulet plantation home,” reported the New Orleans States in 1926, “is now used as the Mercy Hospital administration building.”

In 1953, the Sisters of Mercy, needing modernized facilities to serve an increasingly lakeward-shifting population, purchased land on spacious Jefferson Davis Highway at Bienville Street to build a new $3.5 million Mercy Hospital.

The pending move did not bode well for the Saulet House. The historic preservation movement was nascent at the time, and no ordinances forbade razing historic structures outside the French Quarter. More so, a major expressway and bridge were slated to cut through the neighborhood, one ramp of which would later trigger the destruction of the Delord-Sarpy House, a contemporary of the Saulet House. None of the 1920s wards would be needed anymore, and together with the 1832 building, the complex occupied a sizeable parcel of valuable real estate.

Voices of protest weighed in. “It seems incredible that old buildings expressive of taste and culture should be demolished in the name of progress,” wrote Mrs. Alexander P. Knapp in a 1954 States editorial. “Will that be the fate of the Villa Saulet?” A fire in the attic three years later caused $40,000 in damage, on a property in which the land was probably worth more than the buildings. The whole complex became, according to The Times-Picayune of March 20, 1959, “deserted” and “run-down nearly beyond repair.”

That’s when the wrecking ball swung.

Two years later, food-retail innovator John Schwegmann paid Mercy Hospital $257,500 for the vacant half-block, with plans for a modern supermarket, complete with “rooftop parking for 160 cars, (with automatic elevator), air-conditioned and with 10 check-out counters on the 82,000 square foot site.”

Operating into the late 1990s, Schwegmann’s has itself become a part of New Orleans history. The Robért’s, too, closed, when Hurricane Katrina made its infamous history. In 2019, after demolition of the market shell, construction began on the Delaneaux Aparments, marking a shift to high-density residential use for really the first time in this parcel’s history. As for Mercy Hospital on Jeff Davis, now Norman C. Francis Parkway, it later became the Lindy Boggs Medical Center, and remains vacant since Katrina.

Though no trace of the Saulet House may be seen at 1321 Annunciation, at least two circa-1840 townhouses once owned by Saulet kin still stand on 1216-1222 Annunciation St. Their architectural style and chain of title link the modern-day Lower Garden District to its origins, as four faubourgs surveyed upon four plantations traceable to Spanish colonial times.

Richard Campanella is a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture and author of The West Bank of Greater New Orleans; Cityscapes of New Orleans; Bourbon Street: A History; and other books. Campanella may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, or @nolacampanella on Twitter.