Nineteenth-century New Orleans was a city of middlemen. Here, financiers, agents, factors, traders, merchants and lawyers stewarded the flow of commodities between hinterland and foreland, and each profession had legions of supporters and enablers. Great wealth accumulated in the process, but so did risk — which created an opportunity for yet another profession: actuaries.

Low-profile as it was, the New Orleans-based insurance industry played a key role in the economic development of the region, pooling the risk and protecting the value of everything from cotton bales to speculative railroads to fire-prone buildings. Some companies even insured slaves. City directories throughout the 1800s listed scores of actuaries, and, like banks, insurance firms looked to architects to project a sense of legacy and permanence for their enterprises — the very things claimholders wish to be assured of before paying their premiums.

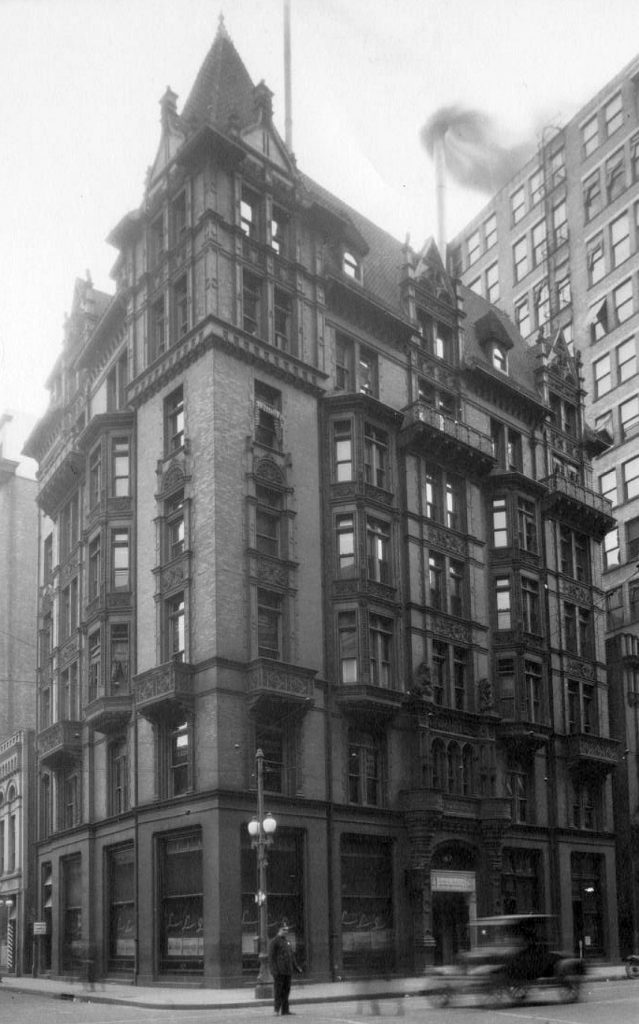

One such example was the Liverpool & London & Globe Insurance Building, designed by Thomas Sully and erected in 1895 at 204 Carondelet Street. The “L&L&G Building” lasted all of one generation, but while it stood, it was one of the most eye-catching edifices in the city.

Described at the time as “being put together on the French chateau style of architecture,” the building’s sponsors were nonetheless purely British. Liverpool & London & Globe began in England as three separate companies. The first was the Globe Insurance Company, founded in 1803 to cover fire and life policies in the Cornhill and Pall Mall districts of London; the second was the Liverpool Fire and Life Insurance Company, founded in 1836; and the third was the London Edinburgh and Dublin Life Insurance Company, established in 1839.

Liverpool and London merged in 1846, and five years later the company opened an office in New Orleans, within steps of the region’s chief financial houses at Carondelet and Common. “This old established, wealthy firm,” read its announcement in The Daily Picayune on November 7, 1851, “is now prepared to insure against Fire Risks in New Orleans on the most advantageous terms.” Capitalized at $10 million, L&L arrived at a fortuitous time and place: only 10 months earlier, on the same block, the St. Charles Hotel, among the most splendid lodges in the nation, came crashing down in a terrible blaze. (Owners rebuilt in 1853 in the same spot, this time with fire insurance.)

Click images to expand

- Liverpool, London and Globe Insurance Building in the 1910s, courtesy HNOC 1979-325-598

- Thomas Sully’s L&L&G building at center, between his St. Charles Hotel and Hennen Building, seen here in 1919. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

Liverpool and London merged with Globe in 1864, and in 1866 the Gardner’s New Orleans Directory listed the enterprise as “Liverpool, London and Globe Insurance Company, office corner Carondelet and Common. Capital in gold, $18,000,000. A. Foster Elliot, Agent.” Over the next 30 years, as a modern American downtown arose all around, L&L&G would outgrow its plain, four-story antebellum row buildings. An insurance firm with the wherewithal of L&L&G had to keep up its architectural appearances, and among the best-suited architects to do that in circa-1890s New Orleans was Thomas Sully.

Born in what is now Gulfport, Mississippi in 1855, Sully honed his design skills not through formal academic training but through apprenticeships and autodidacticism. After working in Texas and New York in the 1870s, Sully settled in New Orleans in 1881 and launched an architectural practice, just as the region’s postbellum malaise gave way to economic rigor. Sully became remarkably busy, his success stemming from his willingness to collaborate with notable designers; his adoption of new technologies such as steel frames, concrete pilings, elevators and electricity; and his alacritous embrace of late-Victorian fashions, from Neoclassical to Renaissance Revival to Tudor, Queen Anne, and Romanesque. One gets the impression that Sully never declined a prospective client nor rejected a fashionable style; he designed numerous uptown mansions for prominent families, including his own, and took on varied projects ranging from banks to yachts to orphanages.

Sully’s biggest commissions came at the height of the Gilded Age, when he designed three major steel-frame buildings within a block of each other. They were the Hennen (Maritime) Building at 201 Carondelet (completed 1895), the third St. Charles Hotel at 201 St. Charles (1896, completed two years after the second lodge burned, as did the first), and the dazzling new Liverpool & London & Globe Insurance Building precisely in between, at 201 Carondelet.

Demolition of the corner sections of the antebellum L&L&G Building took place in early 1894, shortly after the January conflagration at the adjacent hotel, while insurance agents continued working in their Common Street units. Sully’s site, rather small and parallelogram in shape, was then prepared for the insertion of 359 fifty-foot yellow pine pilings upon which the steel and iron frame would rest, much like Sully had designed for the Hennen Building. The steel structure would allow the edifice to rise higher and stand sturdier than one with load-bearing walls, while also earning the stamp of “fire-proof” — appealing to a company specializing in fire insurance. “The new building, [costing] a quarter of a million [dollars,] will be one of the most ornamental structures in the city when completed, if not among the most substantial as well,” predicted the Daily Picayune on October 26, 1894, as the seven-story tower took shape.

This was the same article that had characterized Sully’s design as “French chateau style” — probably more Second Empire, with a Renaissance flair. It went on to capture Sully’s penchant for features like “gray pressed brick with chocolate terra cotta trimming and a roof of red German tile…extremely ornamental.” Fully five percent of the entire project’s cost went into the terra cotta ornamentation, including elaborate balconettes, bay windows with detailed fenestration, and a 16-foot-high entrance on Carondelet with two massive columns topped with the company’s coat of arms. White marble and Italian mosaic dominated the interior, under electrical chandeliers, and the two fastest elevators in the city accessed 45 two-room offices, each with windows overlooking Common or Carondelet and waiting rooms in the interior. “There will be lavatories on each floor, [plus] mail chutes and steam heaters in every room,” reported the Picayune. “One of the new features to be introduced will be a parlor for the lady patrons…located on the third floor.” L&L&G itself occupied the sixth floor, just below the pyramidal turret and mansard roof where records would be stored. All other offices were rented out.

The L&L&G Building opened on schedule on October 1, 1895, said by its constructor to be “one of the finest buildings in the United States; not so large as many, but a gem in its way.” Total cost topped $300,000. For the next 33 years, the L&L&G Building would serve as home to dozens of businesses — some for middlemen, but because New Orleans in the early 1900s was becoming less of an entrepôt and more of a regional service center, it also rented to doctors, real estate agents, investment advisors, tutors, and skilled-trade businesses like that of Ike Meyer, a well-known tailor. New Orleanians knew the building for its elegant script of the letters L, L, and G traced across the ground-floor windows and for its unique gray-and-brown color scheme. Perhaps what most struck the eye was the building’s tall and slender massing compared to its highly detailed steep mansard roof, giving it something of an extruded look. Together with its flamboyant façade, the overall affect was rather whimsical, like a fantasy castle, or a French chateau in a fairy tale.

It was not the sort of look — or size — that would age well.

In 1919, L&L&G was bought out by the Royal Insurance Company, and while the old name continued in use, the change precipitated a rethinking of the company’s global strategy. Commercial property values, meanwhile, soared in downtown New Orleans, and much larger modern buildings were being erected all around, among them the Hibernia Tower (1922) across the street, 355 feet high and the tallest in the state. This part of Carondelet was known at the time as “the Cotton District” as well as “the Wall Street of New Orleans,” and corner properties such as L&L&G’s were particularly valued for their prominence and accessibility.

In 1924 the American Bank purchased the L&L&G property plus adjacent lots, and four years later the owners made plans to replace it with the much-larger American Bank Building. “Physically speaking,” reported the New Orleans Item on February 12, 1928, the L&L&G Building, at “34 years old[,] is in good condition, but it is of an obsolete type, and it must give place to modern development. That in itself is a lively comment on New Orleans today. No longer is this city content to do with makeshifts. Even the Vieux Carre is being modernized….”

Demolition began in October 1928. Once the site was cleared, engineers extracted the 359 pine pilings from 1894 and attempted to re-use them, but they quickly deteriorated with exposure to the air. Instead, the holes were filled with sand and 1,653 new yellow pine pilings were driven into the ground, upon which a steel frame was erected for the 24-story ziggurat-shaped American Bank Building (1929), featuring Art Deco stylings and elements of Modern Gothic topped with a glowing aluminum lantern — quite the repudiation of Sully’s quaint French chateau look.

The L&L&G Building, despite its distinct appearance, never really caught the fancy of residents, nor of photographers or architectural writers. As for the American Bank Building, its financial occupants moved out long ago, and the structure was renovated in 2008 for apartments and renamed 201 Carondelet. No longer a “city of middlemen,” downtown New Orleans has become increasingly devoted to hospitality and residency, and many of the contemporaries of Thomas Sully’s L&L&G Building are no longer filled with cotton samples and actuarial tables, but with kitchens and bedrooms.

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture is the author of “Bourbon Street: A History,” “Bienville’s Dilemma,” “Geographies of New Orleans” and other books. Campanella may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu , or @nolacampanella on Twitter.