“Exchanges” were important buildings in antebellum cities, particularly a bustling mercantilist port like New Orleans.

They were essentially places where people met to conduct business. But because the assembled parties usually had other needs and desires — for banking and legal services, reading rooms and studies, lodging, recreation, entertainment, victuals and libations — exchanges accommodated a much wider range of programming.

Entrepreneurs created ornate multi-use, multi-service “shared spaces” with sundry amenities catering to itinerant businessmen, and as such exchanges became key nodes in cities’ social and economic geography.

Most of the more opulent hotels in antebellum New Orleans, such as the St. Charles and St. Louis, billed themselves as exchanges — roughly the equivalent of modern conference hotels — as did many “coffee houses” (saloons).

One of the best-known exchanges in the early 1800s had so many uses and owners that just about everyone referred to it differently. Located at what is now 501 Chartres, the enterprise started as Tremoulet’s New Exchange Coffee House and became Maspero’s Exchange in 1814, then Elkin’s Exchange after Pierre Maspero died in 1822.

John Hewlett renamed it Hewlett’s Exchange by 1826, although the enterprise also went by the Exchange or New Exchange Coffee House, Hewlett’s Coffee House, or, for Francophones, La Bourse de Hewlett. The two-story corner structure boasted, behind its Venetian privacy screens, a 19-foot-high ceiling, four chandeliers, framed maps and oil paintings (described by one Northerner as “licentious”), wood-and-marble finishing, an enormous bar with French glassware, and billiards and gambling tables upstairs.

Hewlett’s Exchange buzzed with trilingual auctioning activity for everything from ships to sugar kettles to human beings, and it was likely here that a young Abraham Lincoln witnessed a slave auction on his 1828-1831 flatboat visits to New Orleans.

It was in this milieu that an Anglo-American banker and merchant named Samuel Jarvis Peters recognized a business opportunity. Peters realized the city’s commercial core was spreading upriver from the old Creole-dominant Chartres-Royal corridor and into the American sector on the other side

of Canal Street. An exchange built in the heart of this expanding but bifurcated commercial district,

he reasoned, might prosper for its convenience to both Creole and American populations and their

visiting colleagues.

So motivated, Peters amassed $100,000 through a joint stock company and acquired a parcel at 18

(now 124-132) Royal Street, steps off Canal and with key rear frontage along the recently created

Exchange Place (now Exchange Alley).

In 1835, the company commissioned the architectural partnership of James Gallier Sr. and Charles Dakin to design what would be called the Merchants’ Exchange. This was the Ireland-born Gallier’s first summer in New Orleans, and the transplanted New Yorker was already busy designing what would become two of the city’s foremost landmarks, the St. Charles Exchange Hotel in the American sector and now the Merchants’ Exchange.

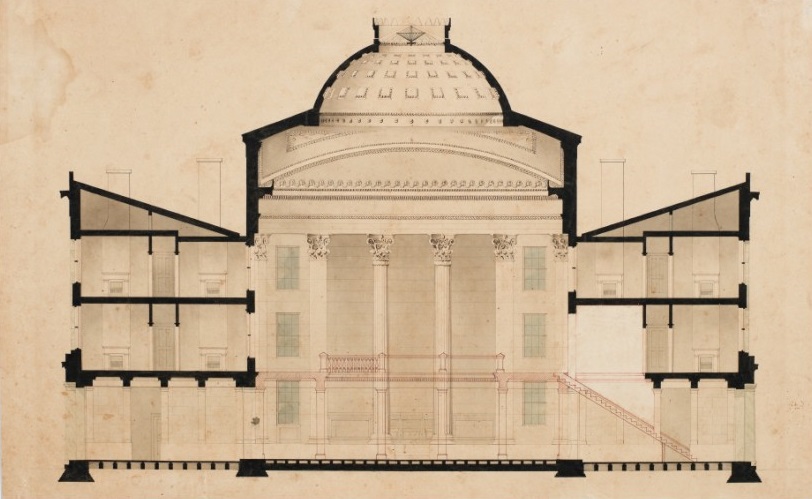

The St. Charles had an entire block at its disposal, with arteries and open skies all around. Not so the site for the Merchants’ Exchange: extant buildings hemmed in the parcel, blocking sunlight, and the narrow confines of Royal Street and Exchange Place could hardly showcase a prominent structure. But the site had ample dimensions, 80 feet long by 120 feet deep. Gallier and Dakin decided to compensate for the site’s limited frontage conditions by capitalizing on its expansive volume.

So they shifted the design emphasis away from the horizontal dimension in favor of verticality, and away from the exterior in favor of a lavish interior.

What resulted were two separate three-story wings, one facing Royal and the other Exchange, featuring subdued façade fenestrations which one observer described as a rather “plain and bold” Greek Classicism, four sets of deeply inset squared-off apertures on either side of a centralized main entrance.

But what awaited inside would astound the visitor: a spacious rotunda uniting the two wings, topped with a stunning dome and florid skylight. Architectural historian Samuel Wilson Jr. described it as “one of the first great monumental interior spaces ever seen in New Orleans,” a soaring atrium bathed in natural light surrounding by walls with towering pilasters and Corinthian capitals.

The plans initially drew skepticism. “The design for the dome and roof over the large room was somewhat peculiar and caused a good deal of criticism among the builders,” recalled Gallier in his 1864 autobiography. William Nichols, an architectural emissary of Neoclassicism in the South and later Louisiana’s state engineer, “pronounced that the building…would be insecure and the dome could

not stand.”

But Gallier, who had based his calculations on the guidelines of noted English structural engineer Thomas Tredgold, stood his ground and convinced his clients and builder Daniel H. Twogood his plans were sound. “Everything was finished in due time,” Gallier reported proudly, “and has remained firm and secure to the present day.”

Opened in 1836, the Merchants’ Exchange would host a head-spinning array of uses, programs and occupants. In today’s parlance, it was “shared space:” flexible public space held in the private domain for multiple users day and night.

In addition to auction rooms, meeting areas and trading floors, the ground floor hosted the U.S.

Post Office, a key tenant that made the building relevant and known to all. (Curiously, according to the Daily Picayune, letters in English were delivered to the Exchange Place entrance, “while letters in foreign languages, and those addressed to ladies, were delivered in Royal Street.”)

There was also a barroom right next to the Post Office, which surely benefited from the foot traffic, and offices leased to various agencies and enterprises. The second floor had a popular Reading Room stocked with the latest tomes and newspapers and frequented by a loyal patronage paying $10 annually.

“There are two bulletin boards in the room,” reported the Daily Picayune in 1840, “one for ship…arrivals and clearances; the other…containing the latest and most important news.”

For years the second floor also housed a city court and the Federal District Court, and it was here in 1857 that filibuster William Walker was tried and acquitted for violation of neutrality laws in his notorious adventurism in Nicaragua. On the third floor was a Billiard Club and parlors for chess games, smoking, and general socializing, all with the business of business at hand. (As for Gallier and Dakin’s original skylight, it had been destroyed by a lightning bolt in 1841 and replaced with tin.)

The Merchants’ Exchange had a particularly sumptuous atmosphere at night.

Observed writer and future New York City mayor Abraham Oakey Hall, after perambulating inside the gas-lit chambers one evening in 1850, “yonder is the cotton broker, with the fluctuations of the market…penciled on his face[;] near him is a sugar broker, fat with perpetual tasting of the sweets of his life…. In one corner the banking agent [chats] familiarly with the jolly planter who has just doffed his hat [to] a passing factor[;] in another corner [sits] a sallow-faced man versed in the tobacco mysteries [of] the London market…. Of all the crowd, perhaps not one calls the city his home, from birth or choice…. All [are gathered here] intent on speculation and accumulation, working for them all the day, dreaming of them by night.”

Here was gathered the empowered elite of antebellum life, the apex of the Southern socio-economic pyramid which rested squarely on enslaved labor.

As for slave auctions, a bookseller who worked in the Exchange in the 1850s told the Daily Picayune many years later that after the Post Office moved to the Customs House in 1861, the rotunda “was rented to the Associated Auctioneers of the city, who used it as a place for the sale of real estate and slaves at auction.”

Incredibly, even after federal troops seized Confederate New Orleans in May 1862, “the sale of slaves went on briskly for several weeks. There seemed to be no restriction put on these sales….” An 1864 article in Daily True Delta referred to the building as “the Merchants’ and Auctioneers’ Exchange.”

The fall of the planter regime and the disruption of trade during and after the Civil War upheaved the commercial community and its spaces, among them the Merchants’ Exchange, which had already lost its main postal and judicial tenants and, unlike its competition, had no hotel income to fall back on.

Worse yet, by the time regional commerce began to recover, various industries now wanted their own exchanges rather than shared spaces. Cotton firms formed the Cotton Exchange in 1871; food merchants created their Produce Exchange (now Board of Trade Plaza) in 1880; sugar merchants formed the Louisiana Sugar Exchange in 1883 and included rice in 1889; and a Stock Exchange formed among the brokers of Gravier Street in 1906.

There was also a Mechanics, Dealers and Lumbermen’s Exchange; a Mexican and South American Exchange; an Auctioneers’ Exchange; and a Fruit Exchange, among others. The antebellum model of the all-purpose space had become a victim of its own success, and the former Merchants’ Exchange became just another downtown commercial building.

Parts of the structure became an illegal gambling hall (probably keno or faro, which were all the rage in this area), while a restaurant and low-rent boarding house filled other rooms. Known by the shady euphemism “No. 18 Royal Street” (excerpts from a 1892 Daily Picayune crime report: “row in a Gambling House [at] No. 18 Royal Street…crowded with people….attacked… with a knife…previous trouble in the place…second disturbance within a week….”), the edifice found itself sandwiched between the ribald New Tivoli Varieties Concert Saloon and another dicey gaming house.

Other incongruous tenants in the 1890s-1900s included the Fourth Battalion of the Louisiana State National Guard, a Chinese laundry, and the Audubon Athletic Club (1890), which put on boxing matches in the rotunda. A fire in 1903 damaged the graceful dome and led to its remodeling into a standard rooftop monitor.

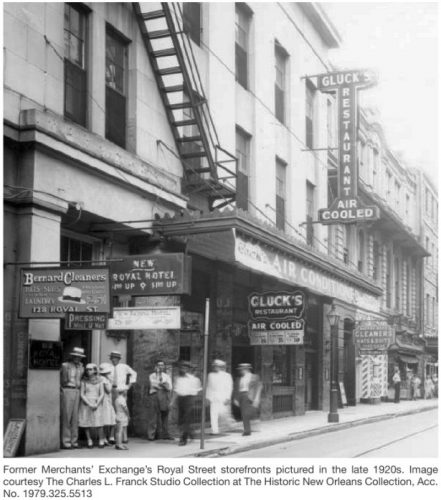

What breathed new life into the old building was the enterprise of a man named Henry Gluck, who opened an eatery downstairs around 1903. Gluck’s Restaurant would become a favorite epicurean rendezvous, known for its German, French, Italian and regional dishes, and it brought a moneyed clientele into the building.

The Gallery Circle Theater would later open on the second and third floors, and by the 1940s-1950s, shops filled the Royal Street storefronts, among them a Mexican curio vendor, a shoe shine, and Aunt Sally’s Original Creole Pralines. The old Merchant’s Exchange had once again become multi-use, and patrons would often frequent both the restaurant and theater during a night out on the town.

Such was the case on December 2, 1960, when the recently renovated Gluck’s did a brisk Friday night business and 225 people enjoyed a comedy called “The Front Page” in the playhouse upstairs.

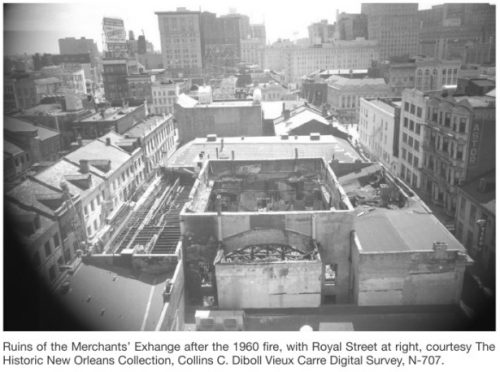

Shortly after the curtains fell, at 11:40 P.M., employees smelled smoke and spotted flames in the theater. Over the next four hours, according to a front-page Times-Picayune report, 140 firemen used 33 pieces of equipment to douse the inferno, as sparks erupted into the sky and black smoke enveloped Royal Street.

The roof caved in and the floors below pancaked, injuring four firemen in the process. By dawn, Gallier and Dakins’ gorgeous interior was open to the street and strewn with charred debris amid tenuous exterior walls.

Enough remained to give cause to the Louisiana Landmarks Society to advocate for its stabilization and reconstruction, but because the 100 block of Royal lay outside Vieux Carré Commission jurisdiction, no legal means could prevent its demolition. The site was cleared in April 1961, sold in December for $300,000, and redeveloped in 1969 with a Holiday Inn, now the Wyndham Hotel.

Investigators determined a transient pyromaniac had ignited the blaze in the restroom of Gluck’s after ordering a hamburger — a pointless and banal end to a storied gem.

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of Bourbon Street: A History, Bienville’s Dilemma, Geographies of New Orleans, and other books. He may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu or @nolacampanella.