This story appeared in PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

If ever there was a town made for theater, New Orleans fits the playbill. Its populace, historically and today, seems to relish performance and spectacle, to the point that both spill out into the public space.

In the 19th century, the dramatic arts formed an industry here, as lucrative as it was influential, and its offerings spanned the gamut of style and sophistication on both the French and American sides of town. Impresarios programmed everything from Shakespeare to satire and from melodramas to minstrelsy, along with operas, symphonies, balls, vaudeville, and at the turn of the 20th century, moving pictures. In an era before modern media, playhouses provided an escape from quotidian monotony, offering an accessible amusement where patrons could exhibit their social status.

Not coincidentally, theaters often experimented with new technologies and innovations, among them gas illumination in the 1830s, electrical illumination in the 1880s, moving pictures in the 1890s, and air-conditioning in the 1920s. It was Bourbon Street’s clever fusion of performance and dining that spawned its nightclub scene, which in time would develop into the entertainment strip of today. The early 1900s also saw the peak of the “theater district” in and around Canal Street at Rampart and Basin — home in 1910 to 14 theaters and other performance venues. By 1930, New Orleans had at least 65 live-performance theaters, 63 dance halls, and 56 motion-picture theaters.

Among the most innovative playhouses were the Tulane and Crescent theaters, built in 1898 fronting Baronne and running along 900 Common St. to University Place (now Roosevelt Way). A predecessor of the multiplex, the Tulane and Crescent were two similar, but structurally separate, venues designed for musical and theatrical performances and later adapted for picture shows.

The name Tulane was not incidental; here had stood the main campus of Tulane University (previously the University of Louisiana and originally the circa-1834 Medical College of Louisiana) starting with its 1848 construction until shortly after the campus was relocated uptown in 1894. The university continued to own 900 Common, and after it cleared away its antebellum complex — three temple-like edifices of the Greek idiom, designed by James Dakin — it leased the land to investors Klaw & Erlanger to create the Tulane and Crescent theaters.

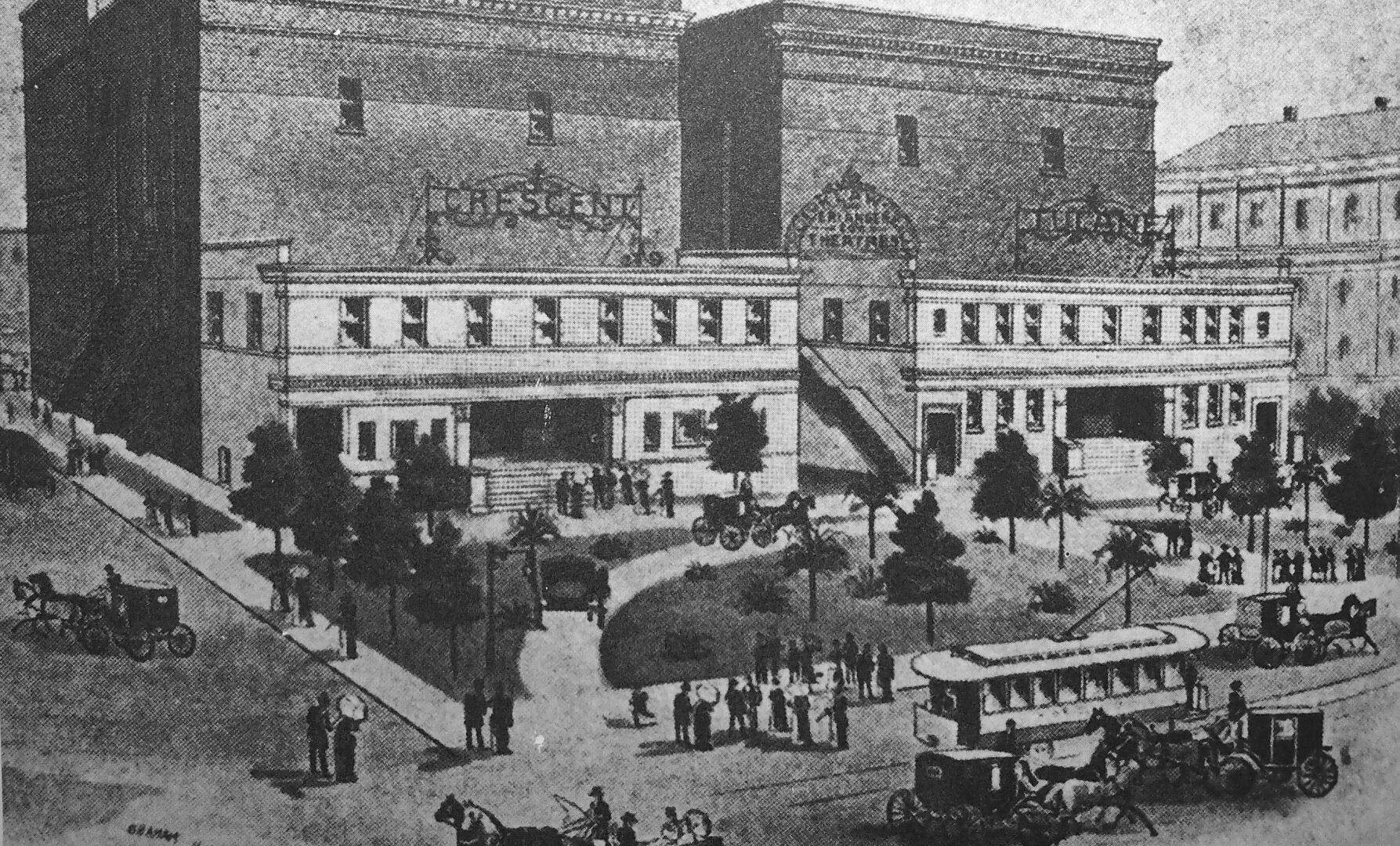

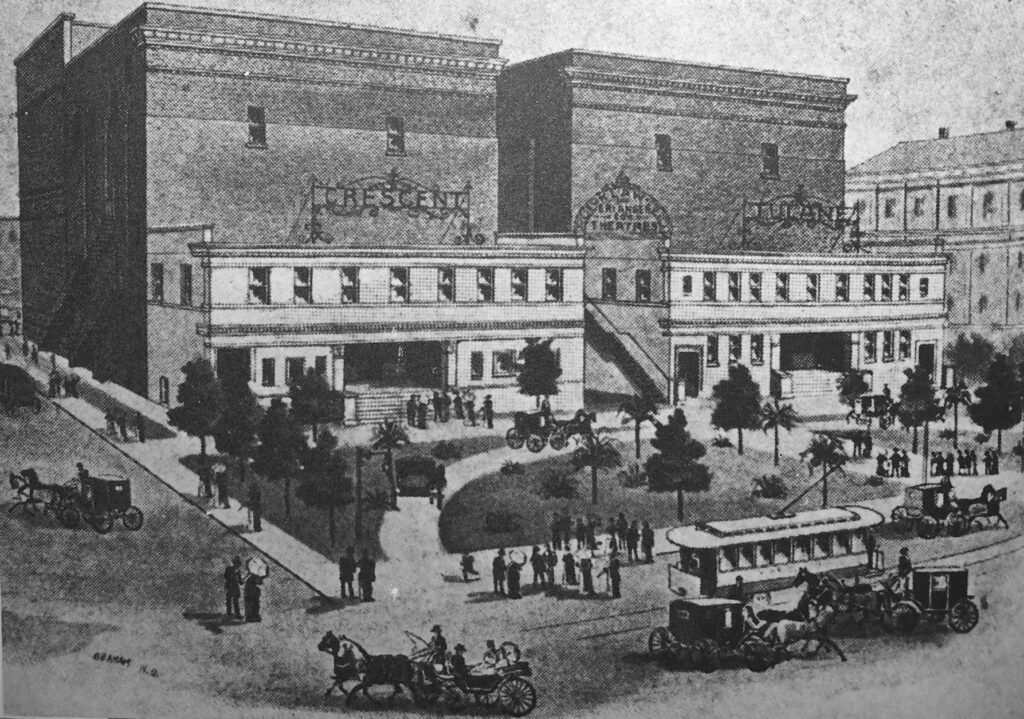

The original design of the twin theaters featured a great lawn in front of the buildings. Image courtesy of Leonard V. Huber

This 1922 aerial view shows the Tulane and Crescent theaters at center. Photo courtesy of Richard Campanella.

Designed by Thomas Sully and erected for $200,000, the dual venues were shaped like parallelograms to conform to the slanted block. Their stages backed to University Place, and both entrances fronted a landscaped lawn on Baronne Street — a rarity for this densely urbanized area. The Crescent was on the upriver side, and the Tulane just downriver; both had two-story lobbies facing the lawn, which opened into four- to five-story auditoriums.

The theaters were surprisingly modern, sans the ornamentation typical of this Late Victorian era and of which Sully indulged notably in his other projects. The buildings did, however, feature three elaborate cast-iron signs propped up above the lobbies, one spelling out CRESCENT, the other TULANE, and the third arching over the alley in between.

Klaw & Erlanger programmed the theaters to appeal to different segments of society. The Crescent “seated 1,800,” wrote historian Leonard V. Huber, and “was designed as a popular-price theatre to continue the sort of offerings that Klaw and Erlanger had been presenting at the St. Charles [Theater],” whereas the somewhat smaller “Tulane catered to a clientele that had patronized the Academy of Music” (which may explain its smaller size).

To double the hoopla of a grand opening, Klaw & Erlanger staged two separate opening nights, on Sept. 26, 1898, for the Crescent, featuring actor Andrew Mack in The Ragged Earl, and on Oct. 17 for the Tulane, with Nat Goodwin starring in Nathan Hale. Two years later, a Picayune journalist raved how “over 1,000 electric lights illuminate these theaters, and the effect on gala nights is surpassingly brilliant.” The site design added to the appeal, the twin theaters being “in all respects modern, up-to-date playhouses, beautiful and comfortable,” wrote the Daily Picayune in 1898, while “the space in front of the theaters on Baronne Street is being beautified, [and] a handsome lawn of green grass [and] trees and palms will ornament the ground…with paved walks leading through it.”

A crescent-shaped driveway allowed horse-drawn carriages and later automobiles to discharge patrons without blocking traffic on Baronne. Both the Crescent and the Tulane were impressive inside, and while the former tended to feature vaudeville, “the Tulane was accustomed to the cream of the American stage,” wrote Huber, citing names such as Ethel Barrymore and Billie Burke, among others.

The landscaped lawn didn’t last. Within a few years, two sets of four common-wall storehouses were erected on the valuable space, leaving only a narrow passageway for pedestrians on Baronne to reach the theaters. To make up for the lost visibility, the owners in 1906 had the dual entrances enclosed in an arcade of steel and glass, creating an atrium where people could linger before performances and during intermissions, or access the adjacent Hotel Grunewald (now the Roosevelt).

A similar arcade was erected over the passageway to Baronne, making the area an interesting warren of private spaces in the public domain. A photograph from November 1914 captured the strikingly modern glass arcade, when the Tulane presented the musical comedy The Ham Tree, featuring the 42-member McIntyre and Heath dancing chorus, and the Crescent featured the musical farce Bringing Up Father.

The circumstances of the theaters’ decline are not clear; they may have entailed a drop in discretionary spending during the Depression, or their obsolescence vis-à-vis new purpose-built movie houses now open citywide, some with air conditioning. Whatever the cause, market forces indicated too much real estate was yielding too little profit. The twin theaters were razed in the mid-1930s for an Esso dealership and parking lot. The glass arcade followed in 1937, as did the storehouses about a decade later, where the lawn once was.

In 1906, the theaters’ owner had the dual entrances enclosed in an arcade of steel and glass, creating an atrium where people could linger before performances and during intermissions. Image from 1914, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Another 1922 aerial view of Tulane-Crescent theaters at center. Photo courtesy of Richard Campanella.

In 1952, the Shell Corporation commissioned architects August Perez and Associates to design a 14-story office building in the space of the two theaters, and a parking garage with retail stores for where the lawn had been. Initially occupied by Progressive Bank & Trust Company and now called 925 Common (Common Center), the building ranks among the city’s first major expressions of International Modernism — “a complete abstraction, eschewing traditional architectural forms, sculpture and applied ornament,” according to a National Register of Historic Places nomination report written in 2002. “It is a work of minimalist art with space delineated geometrically in a severe and rectangular manner.” Recently converted to residential use and now considered historic, the complex occupied land that, according to Orleans Parish Tax Accessor records, Tulane continued to own until 2016 — the university’s last direct link to its antebellum campus.

Many other downtown theaters and movie houses have since folded, as their patrons moved elsewhere, and their businesses failed to produce revenue commensurate to the structures’ big footprints. Yet New Orleans’ historic theater district endures, with the Saenger, Joy and Orpheum still drawing crowds in this town so smitten with performance.

No trace remains of the innovative Tulane and Crescent theaters, although an idea of their visage lives on in the façade of the Orpheum, built only 20 years later and located just across Roosevelt Way.

Richard Campanella is a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture and author of Draining New Orleans; The West Bank of Greater New Orleans; Bourbon Street: A History (LSU Press), and other books. Campanella may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, or @nolacampanella on X.