This story appeared in the December issue of the PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door monthly? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

The stately Eleanor McMain Secondary School has been an exemplar of Art Deco style since it was designed by architect E.A. Christy and built in 1932. In more recent years, though, the 87-year-old campus had begun to show its age.

Paint was peeling on the facade. The stucco exterior was cracking in places, and the parapets were beginning to lean outwards, causing water intrusion issues inside the walls. The building needed more than a quick paint job to restore the grandeur of the historic school.

In the summer of 2018, NOLA Public Schools began a $5.1 million renovation, with work by Concordia Architecture and Tuna Construction. The project, which wrapped up this fall, was funded by FEMA with help from the state historic tax credit, according to officials at NOLA Public Schools.

Christy was a prolific local architect who designed a number of schools and civic buildings throughout New Orleans during the early 20th century. His work encompassed a wide variety of architectural styles, but the McMain building, at 5712 S. Claiborne Ave., shows his mastery of Art Deco, with the building’s sharp-edged linear appearance and its geometric sculptural ornamentation.

Opening in 1932 as a public school for girls, it was named after Eleanor L. McMain, an activist, educator and social worker who served as the director of the Kingsley House, an influential settlement house in the Irish Channel. McMain, who was alive when the school opened, spoke at its dedication ceremony in 1932, according to the school’s website.

Advertisement

A Times-Picayune article from the school’s opening described the building’s paint scheme as “a symphony of riotous, splashing color.” But over the years, the stucco and cast stone façade had become more muted. Before the renovation, it was washed in faded teal and pink.

A materials analysis, completed in 2011 by Building Conservation Associates for Jahncke & Burns Architects, used forensic samples to reveal that a mossy green paint once covered most of the stucco exterior, with cast stone details painted in a polychromatic scheme of yellow, blue, green and gold leaf.

That analysis influenced the Concordia design team as they designed the new paint scheme for the school. “For us, it was a revealing process, revealing what was there and highlighting the elements that were unique to the building,” said Graham Hill, senior project manager at Concordia. “We wanted to do something that struck a balance between fitting in the neighborhood and making a statement to reestablish the prominence of the building along the street.”

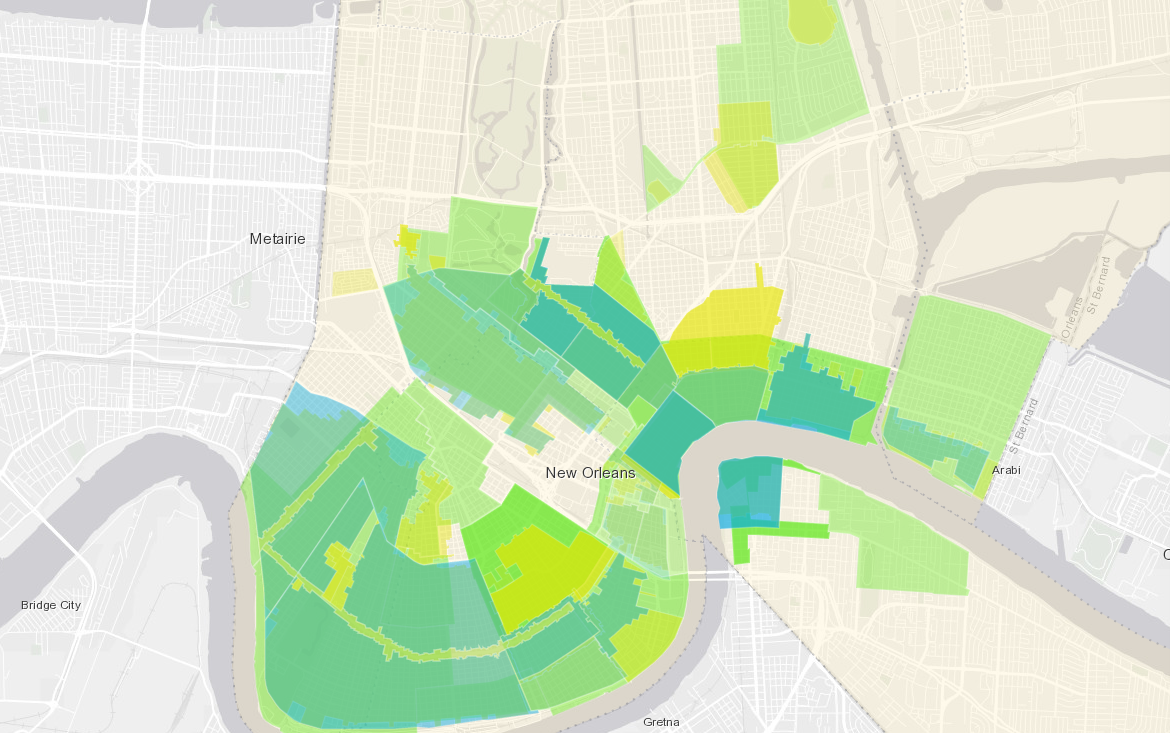

Drawing color inspiration from the landscapes of south Louisiana, the design team developed upwards of 30 potential color schemes before deciding on the new paint palette in shades of earthy green, red, light gray and yellow. When the top three options were presented to the school and school board, the current scheme — named Spring Bayou —was the clear favorite. It was a natural fit for a building with sculptural details that were stylized from local flora and fauna.

Photos by Liz Jurey

The fresh paint adds new levels of dimensionality to the Deco building’s pilasters, gargoyles and architectural details. Contrasting colors emphasize the building’s vertical planes and bring the stylized sculptural details forward.

Original cast stone emblems of a pelican clutching a fish, and an owl clutching a snake, adorn the sides of the buildings. A geometric floral motif runs along the building’s frieze, with additional floral designs at the top of its pilasters. At the school’s front entrance, two sculptures of Acadian maidens symbolizing industry and wisdom, created by sculptor Albert Ricker, are perched atop the parapet at the front entrance. Grinning gargoyles peer down from above the front entrance to greet guests.

“The intricate carvings and gargoyle faces are details that you just don’t see on any buildings that are designed today, and we wanted to make those pop,” said Connor McManus, a project manager at Concordia who developed the color scheme. “It’s rewarding to see what a difference a coat of paint can make,” he said.

“It was important to get it right and make sure it sat well in relation to the neighborhood and was respectful, but also would be inspiring for kids to want to learn and feel energized by as they walk in,” he added.

The building’s rehabilitation encompassed more than a new paint job, though. Bricks beneath the stucco exterior were beginning to effloresce from water intrusion, and interior plaster in some places was cracking and crumbling. Stabilizing the parapets and repairing the exterior masonry was the first step to preventing future water issues.

Advertisement

The building couldn’t be completely sealed off, however, because historic masonry walls need to “breathe” to maintain their structural integrity. “We used a self-cleaning exterior acrylic paint that forms a coating, but it’s not like an elastomeric product that is totally waterproof,” Hill said. “It allows the brick inside to breathe and is porous, but when it rains, it cleans itself.” Elastomeric paints, which were designed to be waterproof, have the tendency to trap water inside the walls of a building and deteriorate the masonry.

Restoring the school’s historic windows was another priority. The cypress window sashes and original hardware were mostly intact, but the glass had been replaced with opaque plexiglass, and, in some places, had plywood boarded over it. Missing panes and deteriorated window glazing caused drafts, putting additional strain on the building’s HVAC system and causing another source of water intrusion.

Architects and contractors meticulously documented the condition of every window in the building to determine the best treatment for each one. Metal windows facing inwards to the building’s courtyard were refinished in place. Contractors from Tuna Construction removed the outward-facing cypress windows, took the windows back to their shop to be stripped and refinished, and then brought the windows back to the school for re-installation. The original casings and trim also were restored.

The historic windows now appear much as they did in 1932, but are more resilient to storm damage thanks to the use of impact-rated glass panes required by modern code. “Typical impact-rated glass is much thicker, because it’s two pieces of glass that are laminated together,” Hill said. “When you’re working within the profile of these old windows, there’s often not enough space in the mullions and muntins to put the new standard laminated glass in. We came up with a solution where we use thinner glass but with a thicker lamination between it, but it achieved the same impact rating that a traditional new window system would have.”

The building’s classrooms are once again filled with natural light, and roller shades in every classroom give teachers the option to filter out the sun when needed.

“Before the project, the windows were opaque and didn’t allow for a lot of natural light,” said Tiffany Delcour, chief operations officer for NOLA Public Schools. “We’re really excited about having windows that bring natural light back into the learning environment. It’s better for student’s eyes, and it also helps with reduction of energy costs with having to not use as much lighting.” The exterior repairs also improved energy efficiency by helping the building’s HVAC system run more smoothly, lowering heating and cooling costs.

A statue of Eleanor L. McMain, the school’s namesake, sits in the original lobby of the building. The lobby’s plaster walls, terrazzo floors and Art Deco details were all restored to their former grandeur. Before (left) by Graham Hill / Concordia. After (right) by Liz Jurey.

Above the building’s original entrance, architects recreated an original Christy-designed light fixture that had been removed at some point during the school’s history. Planters along the sides of the building also were replaced to Christy’s original specifications.

Making upgrades to the building while classes were in session proved to be a challenge, but architects and contractors worked closely with InspireNOLA Charter Schools, the current operator of McMain, to sequence construction so as to disrupt the school day as little as possible. Work focused on sections of classrooms for a period of four to six weeks at a time, while classes in those rooms were relocated to other rooms in the building. When the repairs were completed, classes moved back in and work would commence in another area. By coordinating a tight schedule, the school remained open throughout the construction process without the need for portable classrooms.

The school’s original lobby along the Claiborne Avenue entrance also was restored. Although the main entrance had previously moved to the Nashville Avenue side of the building for accessibility and security reasons, the original lobby was a grand expression of Art Deco style with cast stone details, geometric patterns and terrazzo flooring, but it had been unused for years. Now, the main entrance remains on Nashville Avenue, but the restored original lobby will lead to the school’s front yard, which will be used more frequently for activities after landscaping upgrades.

Live oak trees along Claiborne once obscured the building from view, but with the help of a licensed arborist and the New Orleans Parks and Parkways Department, branches were pruned to improve the health of the trees and give passersby a clear view of the restored school.

“This renovation not only benefits the learning environment for the students and the pride of the school, but I think it’s also giving back to the neighborhood again,” Hill said. “Seeing it as a landmark again in the neighborhood is really rewarding.”

Davis “Dee” Allen is PRC’s Communications Associate and a staff writer for Preservation in Print.

Advertisements