There may be one on your block: An empty house where the mail once piled up on the stoop. Now the mail no longer comes. Maybe someone occasionally mows the lawn or a neighbor keeps up the yard. Perhaps the paint is peeling, but you wouldn’t call the house blighted — at least not yet.

In New Orleans, persistent housing vacancy counterintuitively coincides with sharply rising rents and land values. Homes and apartments sit empty. Some are caught up in title disputes; others are mothballed by owners with hopes of returning one day. Some are owned by heirs who fail to appreciate their value.

Many of these persistently vacant properties are inhabitable or could be with minor repairs. Returning them to occupancy is one part of the solution to the local affordable housing crisis. Two-thirds of renters and one-third of homeowners are burdened by high housing costs, spending more than 30 percent of their income on housing.

A recent PRC investigation found more than 5,000 chronically vacant housing units in Orleans Parish. These empty homes are distinct from the more numerous blighted properties and vacant lots. Returning empty homes to occupancy is the logical cornerstone of local affordable housing policy. In 2018, the U.S. Census Bureau found that 11.8 percent of housing inventory sat vacant year-round in the New Orleans-Metairie statistical area, tying for 10th with Baton Rouge among the 75 largest metros in the United States. However, that figure is based on representative surveys and doesn’t specify neighborhoods. We wanted to take a closer look.

Understanding the data

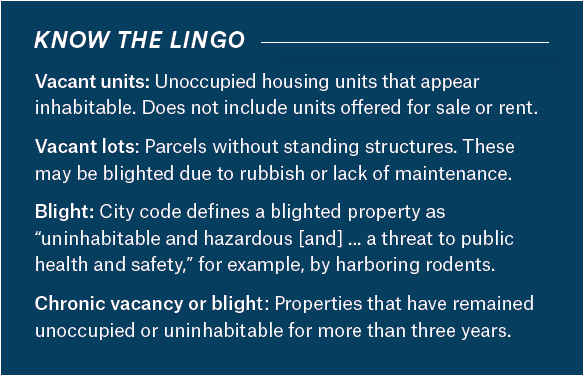

Whether strolling down the street or viewing satellite imagery, it’s easy to spot the more than 15,000 vacant lots in New Orleans, but vacant houses hide in plain sight citywide. Who better to help identify an empty house than the neighborhood letter carrier? The Post Office flags addresses it has deemed vacant for 90 days or longer. This data is available at the census track level via the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Further refined data from the firm Valassis also was made available to PRC by The Data Center, which has used it to track population trends for many years.

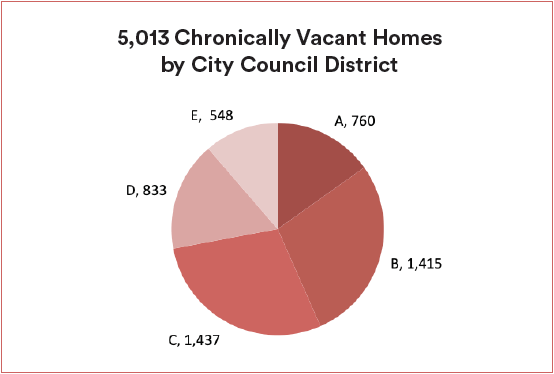

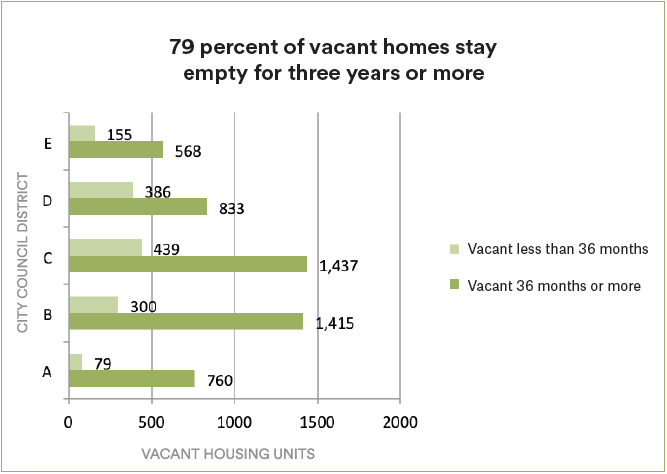

The figures presented here are from the second quarter of 2019. The numbers are by nature conservative: It’s quite plausible for an owner or neighbor to continue picking up the mail at an empty home. Recognizing that the interim vacancy may occur when a dwelling is on the market or undergoing renovation, we went a step further to quantify chronic vacancy. We tallied properties vacant for more than 36 months, and found them to be 79 percent of the total. These 5,013 chronically vacant homes represent a cautious estimate of the city’s empty housing stock.

Those empty homes should not be confused with blighted housing, which is more prevalent. Why then be concerned with vacancy? Because vacant housing can be returned to use faster and at lower costs than a blighted property. Empty units may require only minor repairs and fresh paint before being returned to market. Significantly blighted properties, by contrast, are often structurally deficient and subject to code enforcement fines or other liens.

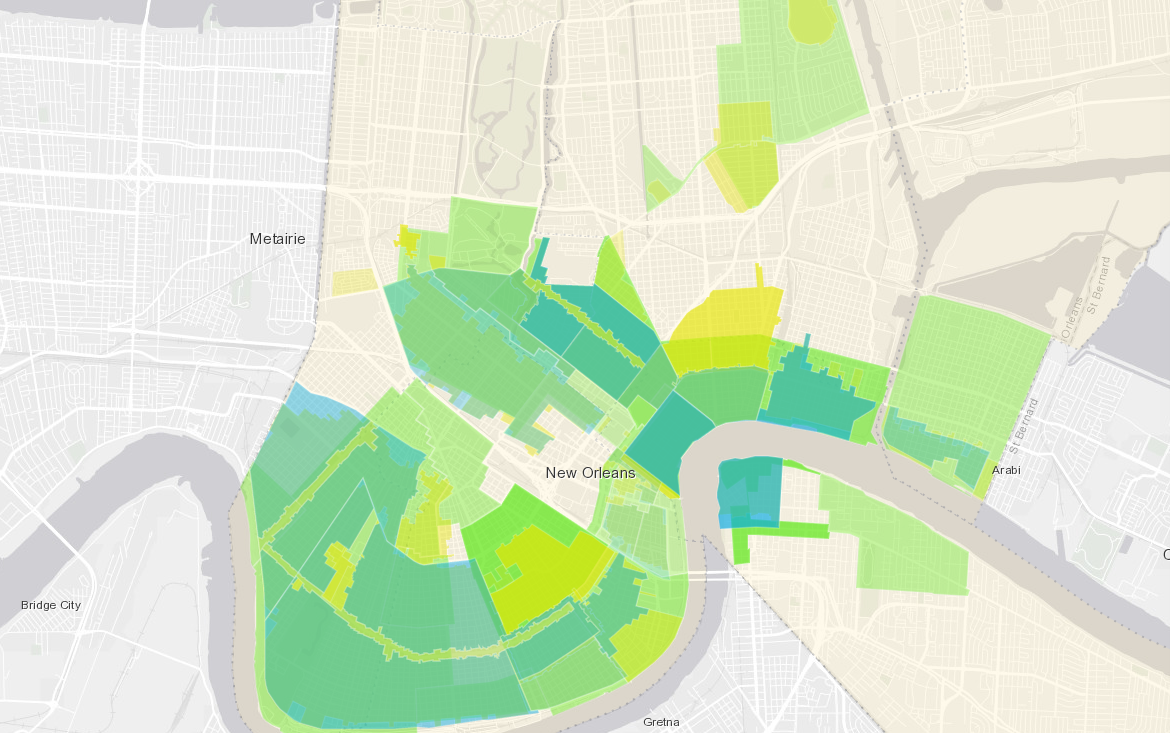

To help make sense of the numbers, we created an interactive online map showing vacancy and blight by city council, historic and cultural districts.

Empty in New Orleans: explore the web map

A citywide phenomenon

Empty homes can be found in every neighborhood of the city. Concentrations of vacancy occur in Algiers, Central City, Broadmoor and the French Quarter, one of the few areas where vacant multifamily units outnumber vacant singles and doubles. Parsing the numbers by City Council district reveals that no district is exempt. The highest total for chronic vacancy — 1,437 — is found in District D (which includes Gentilly, Treme, 7th Ward and St. Roch) followed closely by District B (which includes portions of Uptown, Broadmoor, Central City and the Central Business District). However, this comes with the caveat that our conservative methodology likely undercounts vacant apartments.

Vacancy in historic neighborhoods

Recognition as a historic district does little to fend off vacancy, but that may not be all bad news. Some 43 percent of currently vacant homes, and a majority (58 percent) of currently vacant multifamily units, are located within National Register Historic Districts; 54 percent of vacant homes and 68 percent of vacant multifamily units are located within state-designated Cultural Districts. These districts help unlock state and federal tax credits for historic rehabilitation of commercial property, including rental housing. Furthermore, these rehabilitation tax credits can be used in conjunction with low-income housing tax credits and project-based vouchers for affordable housing.

Numerous developers have successfully applied this model to rehab former schools, such as Bell Artspace and McDonogh 16, into housing, with Pierre Capdau, Holy Cross and Oretha Castle Haley schools soon to follow. However, only a handful of developers have applied that model to the singles and doubles that make up a majority of the city’s empty houses. In part that may be explained by the fact that opportunity costs, such as negotiating sales, obtaining clear property titles and even applying for historic tax credits, increase with each parcel or property.

Based on Valassis data provided by The Data Center, New Orleans Cultural Districts are home to 2,667 vacant street addresses and 758 vacant multifamily units. Many would be eligible for State Historic Tax Credits if rehabbed for rental. New Orleans National Register Historic Districts are home to 2,137 vacant street addresses and 645 vacant multifamily units. Many would qualify for Federal Historic Tax Credits if rehabbed for rental.

Returning home

This investigation provides a snapshot in time. Every day, structures are restored and reoccupied, demolished and abandoned. However, the chronic nature of vacancy suggests that existing market forces cannot be reasonably expected to remedy the problem; innovative approaches will be required.

New Orleans, like most American cities, imposes code-enforcement fines and property tax liens to motivate negligent or absentee property owners. But what are other cities doing to encourage owners to return homes to use? Last year, voters in Oakland, Calif., approved a vacancy tax of up to $3,000 per housing unit per year. Washington, D.C., has taxed vacant properties, both residential and commercial, at a higher rate since 2011. Both cities provide exemptions for economic hardship.

In addition to a focus on blighted properties that sometimes results in demolition, Baltimore’s Vacants to Value program gives a $10,000 boost to purchasers of formerly vacant homes. The Historic Rehabilitation Tax Abatement program in Richmond, Va., incentivizes rehabilitation of existing housing stock by forgoing property taxes on the improvements for a decade. Philadelphia administers a similar program alongside tax abatements for commercial buildings and new construction.

For New Orleans, strictures within the state constitution present hurdles to both punitive and incentive tax strategies. Before attempting to overcome these, the city can build a foundation by collecting more data. Vacancy reporting and tracking was pivotal for Washington, D.C., and is a logical starting point here.

Nathan Lott is PRC’s Advocacy Coordinator & Public Policy Research Director. He can be reached at nlott@prcno.org