This story appeared in the May issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

In the ancient world, iron from India was renowned for its quality. It was noted in Aristotle’s writings and exported as far afield as Egypt and the Roman Empire. It had to be “hot worked,” beaten into shape by a blacksmith under high temperature, to produce a great variety of objects, including swords, helmets, cooking vessels, drinking vessels, even jewelry. This was wrought iron. Cast iron came later.

In casting, hot molten iron was poured into a mold, and once cooled and hardened, the finished object was removed. Initially perfected in China, casting was in use in Europe by the 14th century. As with wrought iron, cast iron was limited to small objects — vessels, utensils, etc. — because iron was too soft for larger pieces, such as columns and beams. Over the centuries, iron’s firmness was improved by adding limited amounts of carbon in the smelting process. It was a ticklish balance. Too little carbon, and the iron was still too soft. Too much, and the iron became brittle, like cheap crockery.

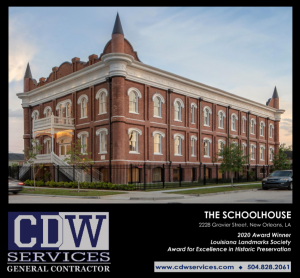

Advertisement

It was Britain that took the lead in advancing cast iron as a medium for building. Sir Christopher Wren included slender cast-iron columns in his design for St. Stephen’s Chapel, Westminster (1714). Then there was the Coalbrookdale Bridge in Shropshire (1775-1776), much noted in engineering schools as a very early, impressive and fully functional structure made entirely of iron.

If we were to date the dawn of the cast iron age, the best year might be 1824. That year British inventor James Nielson developed an improved iron smelting system known as the hot blast process — pre-heating air before it reached the smelting chamber. It enabled large amounts of pig iron to be procured from much lower grade ore, and it greatly reduced fuel costs. Iron to cast became vastly more plentiful in Britain and ultimately in America.

In the rising American cast iron age, the building trades embraced the new medium in various forms, offering lavish ornament at modest price. In northern and mid-western cities, the effect was fairly restrained, confined mainly to stoop railings, fences and gates as well as some structural pieces, such as lintels. After about 1840, whole galleries, verandas and balconies, all in decorative cast iron, appeared in large numbers in various southern cities, particularly New Orleans and Savannah, Ga.

Photo 1: Gallier House, at 1132 Royal St., was designed by architect James Gallier, Jr. as his private residence. It was completed in 1860. Today, most ironwork is painted coach lamp black. The mid-19th-century color pallet ran to more adventurous hues, such as the soft green seen here and a dark burnished gold resembling bronze. Photo via WikiCommons. Photo 2: The Lower Pontalba building. It is speculated that the Baroness Pontalba’s choice of cast-iron filigree to adorn the Upper and Lower Pontalba buildings set a high fashion that quickly spread through the city (1849-50, James Gallier Sr. and Henry Howard, architects). Photo by Wally Gobetz.

Like exuberant vines, these iron devices climbed joyously from curbstone to parapet, enriching the street view. There was a sumptuous feel, following the Victorian Age maxim that too much is never enough. The resulting fanciful effect is compelling — something to celebrate.

This profusion of ornamentation is especially important in the Crescent City; indeed, it is a hallmark recognized far and wide. And it is a distinctive cast iron. “The ironwork of New Orleans has a light, lacelike quality that is unique,” noted Susan and Michael Southworth in their 1978 study Ornamental Ironwork. And so it came to be that cast-iron technology, that ever so British import, shaped and adorned a charming neighborhood we are pleased to call the French Quarter.

With the onslaught of the Civil War, local iron foundries, such as Leeds, turned to producing armaments for the Confederate government. After the war, decorative casting continued. But by the 1880s, filigree ironwork had fallen from fashion. So although New Orleans’ cast iron age was quite brief, it left a rich and bountiful legacy.

Advertisement

There remains an abundance of cast iron in New Orleans for two reasons, one military and the other economic. The city’s building stock was not devastated in the course of the Civil War. In 1862, New Orleans fell to Capt. David Farragut’s U.S. Navy flotilla without a fight. Later, the old center of town, the Vieux Carre, languished as a depressed area, home to a great swath of mostly unimproved rental property. Hence its building stock was not significantly remodeled or replaced.

In other southern cities, where the old town center remained viable, the cast-iron legacy, much of it mid-19th century, was lost, replaced by early 20th-century structures of brick veneer over a newer medium, reinforced concrete.

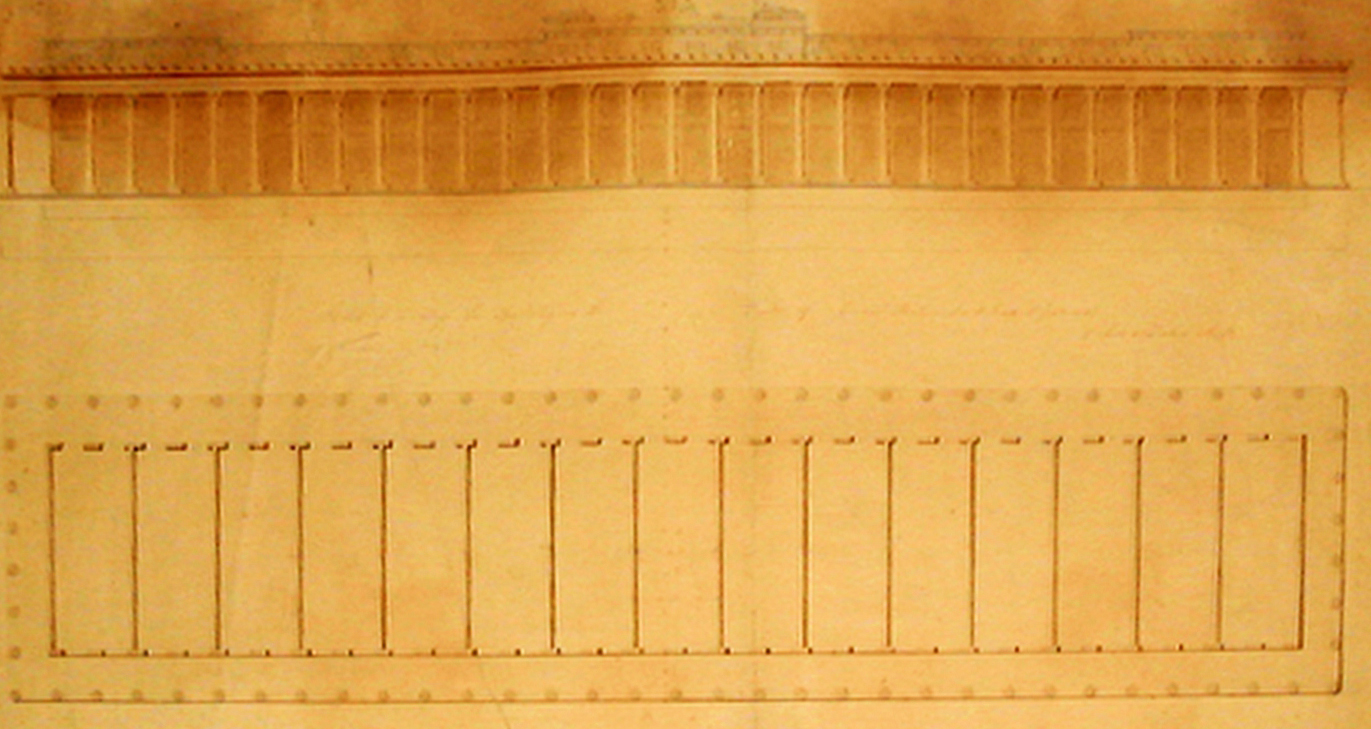

The ultimate tour-de-force was an entire façade rendered in cast iron. In olden times, on a façade one would call “rich,” all columns, decorative panels, etc., had to be laboriously sculpted by a master stone carver. With cast iron, all parts could be quickly cast via repeated use of the same mold, and then bolted together. This was the great virtue in industrial cast iron.

Advertisement

It was a cause championed by American inventor James Bogardus, who was broadly seen as a trailblazer in prefabricated buildings. He published Cast-Iron Buildings, Their Construction and Advantages (1856), hailing the new genre as “fireproof, transportable and efficient.” Bogardus’ ultimate goal was buildings made completely of iron — internal structure and all.

The fully cast-iron front was as close as the Crescent City ever came to Bogadus’ ideal. A number were built mostly in and around Canal Street. Only two are known to remain: 622 Canal St. and 111 Exchange Place. Both enjoy a preeminent place in New Orleans’ vaunted 19th-century heritage. 622 Canal, built in 1859, is a delicious confection in the Baroque style. The elegant 111 Exchange Place, built 1866, transports us to Venice of the early Renaissance.

Under-utilized (vacant above the first floor) for decades, 111 Exchange Place has recently been restored by developer Aaron Motwani using historic rehabilitation tax credits. Its rescue and rehabilitation is a major achievement and a worthy tribute to the Crescent City’s great age of cast iron.

Photo 1: 111 Exchange Place (1866, Gallier and Esterbrook, architects) evokes with authority the early Venetian Renaissance. Its façade is entirely of cast iron, quite a rarity in New Orleans. Photo by Jonathan Fricker. Photo 2: The Garden District mansion known as Colonel Short’s Villa (1859, Henry Howard, architect) must hold the distinction of having the most ornamental cast iron at a single property, including lacey galleries/balconies on three elevations and a massive fence complete with iron cornstalks.

Advertisements