This story appeared in the June issue of the PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door each month? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

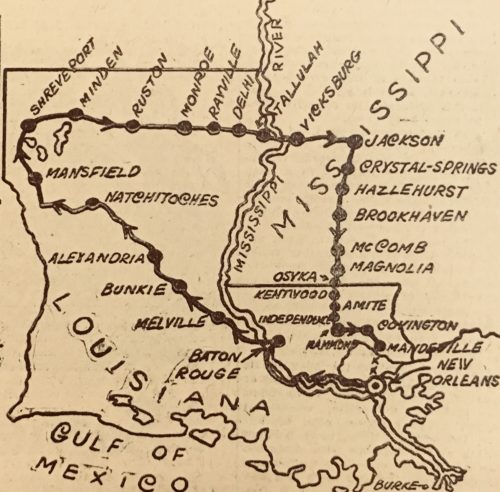

In the early 1920s, Louisiana enacted an intentional plan to build and improve interstate highways, joining them to country, town and smaller city roads. The plan also included connections to old pathways leading to ports, ferries and waterways, as well as to established railroad systems. This project was part of a larger federally led effort to build an accessible, nationwide, navigable network of roads — the very beginnings of the Interstate Highway System as we know it today.

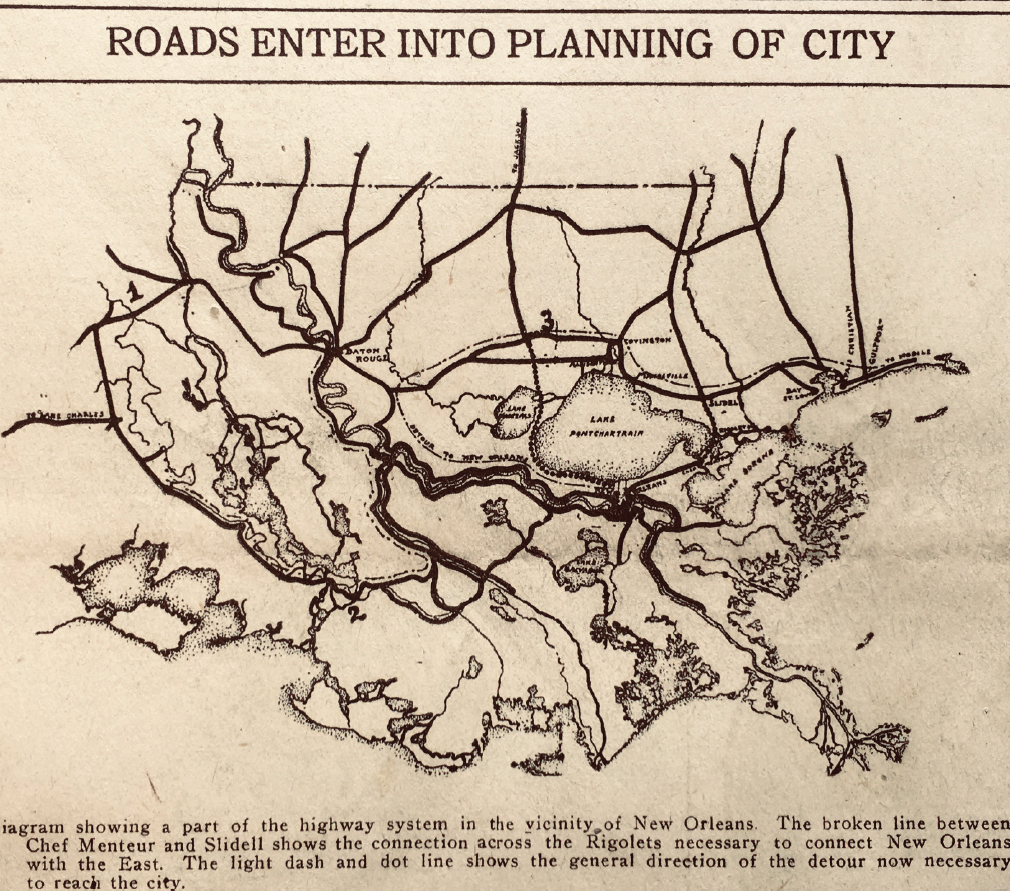

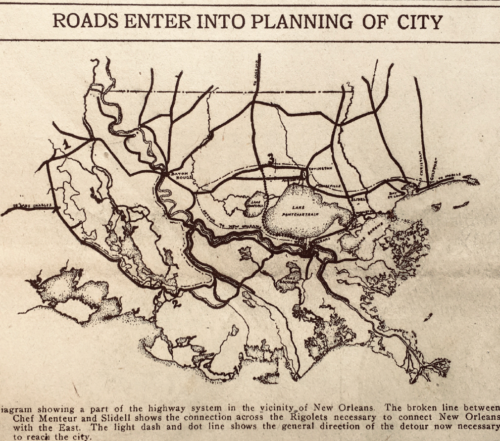

It was no easy task, and it became especially difficult to carryout along the Gulf of Mexico and across the complex waterways of Southern Louisiana. By 1921, the greater New Orleans road system distinctly lacked a way to connect the east part of the city, running along Chef Menteur Highway, to Slidell and across to the Rigolets, a path many of us take today to explore the back roads toward Bay St. Louis, Biloxi and other vacation spots. But this matter wasn’t about vacation voyages at first, for it was vital that the City of New Orleans no longer be cut off from national routes coming in from the north, east and west — or to put it another way, for motorists, “New Orleans lies in a cul-de-sac requiring detour of two hundred miles.”

In a Times-Picayune article from Jan. 2, 1921, titled “City Must Provide for System of Highways”, the author, Milton D. Medary, chief consultant of the Association of Commerce, calls for the city to plot out a complex, but immediately necessary, new roadway system. This system would be built in order to support the passage of thousands of new automobiles that required more navigable and improved conditions. It also would be needed by ruggedized trucks transporting goods on a large scale to places where railroads — garnering decades of investment and capital — had already been laid out. Medary’s plan called for a re-examining of the immediate needs of Louisianans, citing the age-old roads of the Roman Empire, reminding the reader of the roads’ role in the progress of arts and sciences, education and commerce.

Click on images to expand.

His plan was for the railways, waterways and roadways to all function together equally — and his goal was connectivity. He writes, “All power consumed in unnecessary transportation is a charge against all the people.” Medary’s study was in-depth and his thesis was clear: “the isolated position of New Orleans in relation to the highway approach and the undeveloped condition of the highways themselves have in the past made any serious consideration of these gateways in the city unnecessary; but potentially they have as great importance as the gateways to ancient cities…” The study he created was quickly deemed invaluable, and these measures gained much support and cooperation. Over the next few years, these proposed road improvements came quickly, and within the 1920s, the new system began to take shape.

Just a few short years later, the Times-Picayune added a “Motorlog” section that creatively presented step-by-step plans to navigate these new routes, providing the tools for automobile enthusiasts to explore the entire region. So imagine packing up your vehicle to set out on a road trip to some unseen destination along the Gulf Coast — but what if you could see it through the lens of 1925? Well, before Google Maps, there were AAA TripTiks, which took the place of national road atlases, and before those, motorists used elaborately folded paper maps. But in the 1920s, the Times-Picayune took the work out of plotting the path and published hand-drawn, detailed adventure guides for an eager, new generation of “Motorlog” road-trippers.

What is to be found in these sections is a series of treasured travelogues and illustrated maps that reveal how people of the past were able to newly navigate the terrain, in a time when Americans were breaking free from old ideals and realizing the new possibilities of traversing great distances, one tank at a time.

The Motorlogs reveal the way we once set out — on paved, shell, gravel and dirt roads — across a landscape forgotten in time, to explore an environment so precious to us today.

is an original archive of over 30,000 historic New Orleans newspapers from 1888-1929, delivering history on demand through clever curation, graphics and print. Curator Joseph Makkos is using materials from the archive to write this special series for Preservation in Print in celebration of the Tricentennial.