This story appeared in the October issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

This summer, a drive to save one of the world’s first jazz venues was in a race against time and the elements.

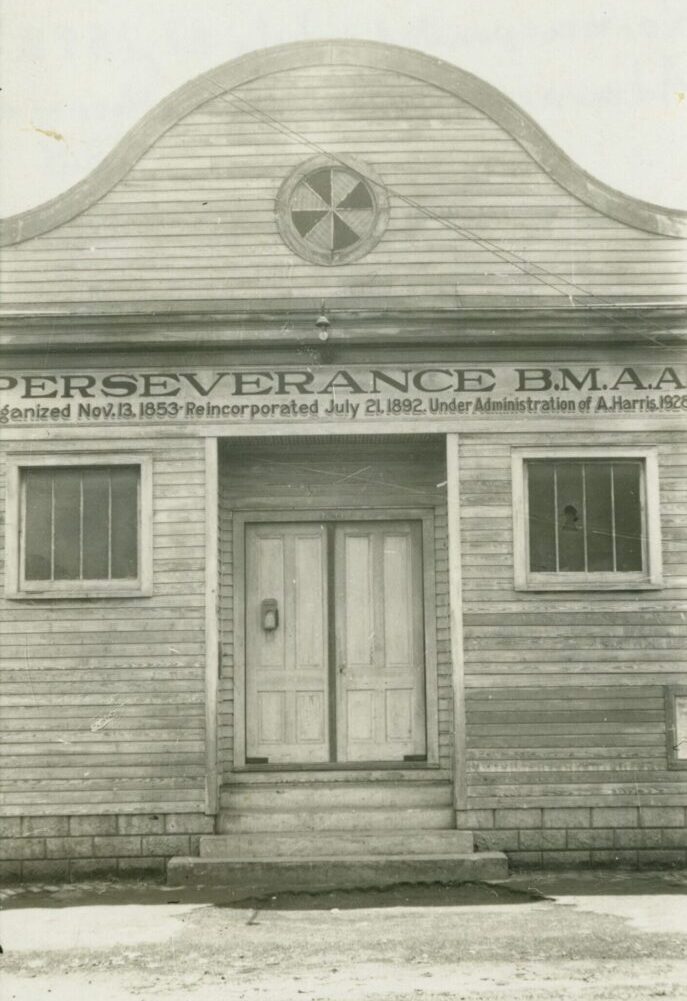

Preservationists had warned for years that the 142-year-old, wood-framed Holy Aid and Comfort Spiritual Church of Eternal Life, also known as Perseverance Benevolent and Mutual Aid Society Hall, was at risk, but it collapsed before the church could raise enough money to repair major damage from Hurricane Ida.

The Rev. Harold Lewis, the leader of the church, had been working since 2005 to make the facility a resource for the surrounding Seventh Ward neighborhood. He sees the collapse as a setback, but not the end of his plans. “I’m committed to this,” he said in September, just weeks after the building collapsed on Aug. 24, almost exactly a year after it sustained major damage in Hurricane Ida. Lewis hopes to rebuild not only to resume services and outreach to neighbors in need, but to open the space to community groups and artists to hold events and performances.

This effort would return the building to the multi-faceted role it played when it opened in 1880 as the headquarters of La Société de la Perseverance, a benevolent society founded by free Creoles of color before the Civil War. The association was one of many to provide medical and burial benefits to members who were denied mainstream insurance because of their race.

The society served a social function, too, hosting concerts and dances at its hall, which included a large open space with a stage and loft for musicians at the far end. Since there were few places where Black people could safely congregate during segregation, it also rented the hall to other groups so they could hold events of their own.

Photo 1: courtesy of The William Russell Jazz Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, acquisition made possible by the Clarisse Claiborne, Acc. No. 92-48-L.52. Photo 2: Perseverance Benevolent and Mutual Aid Society Hall in 1939. Photo courtesy of The William Russell Jazz Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, acquisition made possible by the Clarisse Claiborne, Acc. No. 92-48-L.52.

Around 1900, musicians performing at the hall started playing a new style of music that would become known as jazz. The breakthrough came from bandleader Buddy Bolden, who ad-libbed phrases on his cornet and played with a bluesy feel. (Perseverance Hall was one of the precious few places in which Bolden played that has survived through the 20th century.)

Other giants followed, including bandleader King Oliver, Louis Armstrong’s mentor, and Sidney Bechet, the virtuoso clarinet and soprano saxophonist, who lived in the neighborhood.

The hall was integral to the social milieu that gave rise to jazz. Bolden’s playing there was audible in the nearby home of the Barbarin family, which went on to produce generations of important musicians. One of them, Danny Barker, had childhood encounters with brass band processions outside Perseverance Hall that he’d draw on later in life when he instigated a citywide brass band revival.

Advertisement

The building, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places, hosted dances through the 1940s, and in 1950, with Black insurance companies obviating the need for benevolent societies, it was sold to a Spiritual church. Tapping New Orleans’ tradition of syncretic spiritual practices, Spiritual churches gained a following with services that incorporated tenets of Christianity with prophecy and healing rituals rooted in Africa.

Lewis’ relatives were among the first members of the Holy Aid and Comfort Spiritual Church of Eternal Life, which, by moving into Perseverance Hall, claimed one of the largest facilities of the nearly 100 Spiritual churches then in the city.

While the congregation has kept the name “Spiritual church” ever since, its worship shifted to more mainstream Christianity during the tenure of Lewis’ predecessor, beginning in the mid-1970s. In the period before Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the congregation aged and dwindled, and the flood following the levee failures only made it harder for those remaining to attend.

Lewis took over in the aftermath of the storm, which heavily damaged a rear addition to the building. It dislodged a second-story camelback, leaving it suspended on two large trees, and exposed the area beneath, which was walled off from the main hall used by the church. (The old musicians’ loft, on the back side of that wall, was beyond repair.)

Click to expand images

The building from 2016 to November 2021. Photos via Google Streetview.

The church couldn’t afford to dismantle the rear section of the building, but a grant allowed contractor Jack Stewart, who has preserved a number of the city’s jazz landmarks, to take down the camelback without damaging the original hall.

In the ensuing years, despite the condition of the rear of the building, Lewis continued to hold Sunday services in the main hall and used it to serve homecooked meals to neighbors in need. That space was in poor repair, too, and he pieced together donations to renovate it himself. “I made the windows; I started doing the floors; I did the walls; I redid the bathrooms,” he said.

Lewis is a skilled craftsman, but it was arduous work. With the help of one parishioner and the nephew of another, he was working on the ceiling one day when a piece of sheetrock fell on him. “It knocked me off the ladder, 16 feet to the floor, and the sheetrock fell on me. I hit the floor so hard that I bounced,” Lewis said.

Advertisement

Then, in 2019, a substantial donation allowed Stewart to start doing structural work, and he strengthened the building’s foundation, repairing its brick piers and floor joists. In 2021, Stewart was rebuilding the rear section, when Hurricane Ida forced his crew to evacuate before it could reinforce its old, damaged wood.

“If the storm had come a month later, we would have had the building much more structurally prepared for it,” Stewart said.

As it happened, Hurricane Ida blew over the partially renovated walls and the roof of the rear section came down on top of them. The back wall then had to be demolished, opening the church’s main hall to the elements. The remaining portion of the two side walls leaned toward an empty lot next door, so Stewart installed large wooden braces to keep them upright until a shoring company could right them.

Perseverance Hall, photographed after it collapsed this summer. Photos by Nathan Lott.

At a meeting held at the Preservation Resource Center, the construction team and local preservationists discussed technical options for repair. Then PRC staff and Louisiana Landmarks Society board members met with Lewis to chart a path forward. The society established a dedicated fund for the project, but fundraising was slow this summer while heavy rain softened the ground beneath the wooden braces. At some point during a thunderstorm, the braces gave way, and the whole structure behind the front vestibule collapsed.

The morning before it fell, the PRC partnered with the church to prepare an application to a program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation that offers major grants for Black houses of worship. At the same time, the Louisiana Landmarks Society planned the rollout of the “New Orleans Nine,” its annual list of threatened historic sites, which included the church. Those advocacy efforts continued despite the additional collapse. (Read the full New Orleans Nine list on page 28.)

Stewart said that, given the previous damage to the building, the collapse didn’t drastically change his outlook. The asbestos shingles, roof sheathing, and many of the rafters had to be replaced anyway; now that can happen without worrying about the precarious walls. All of the salvageable wood is still available. Most of the façade and front vestibule is intact, and the foundation is strong.

“I’ve been doing this for 50 years,” he said. “I’ve gotten buildings in worse shape done.”

All he needs is funding.

In the meantime, Pastor Lewis has congregants calling in to services remotely, and he hopes to rebuild the interior of the church himself to make it a gathering place for seniors by day and a venue for shows by night.

“I’m always going toward that sound,” he said. “That means a lot to me because those are the things that I think will bring people back to the neighborhood.”

Advertisements