This story appeared in the June issue of the PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door monthly? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

June 22 is Poverty Point’s fifth anniversary as a World Heritage Site. Being on the prestigious UNESCO World Heritage List means that the site is deemed an important place for all of humanity, worthy of appreciation today and preservation for future generations.

Poverty Point is Louisiana’s first, and only, World Heritage Site and the only cultural World Heritage Site in the American Southeast.

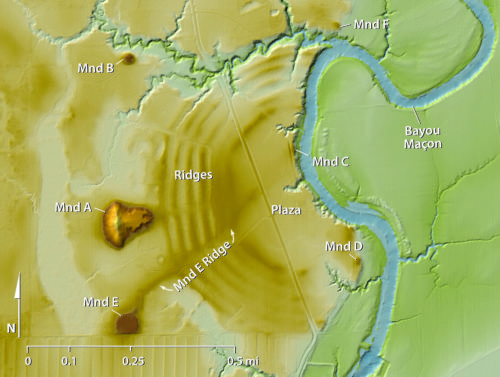

For those unfamiliar with Poverty Point, it is a 402-acre archaeological park in northeast Louisiana that is regarded as the largest and most complex hunter-fisher-gatherer site in North America, if not the world. Dating from about 1,700 B.C.E. to 1,100 B.C.E., this designed landscape includes five earthen mounds (Mounds A, B, C, E and F) and six nested, C-shaped, earthen ridges surrounding a huge leveled, 43-acre plaza.

The concentric ridges are thought to be the living area of the site. From geophysical survey and limited excavation, archaeologists know the plaza once contained large circles of big wood posts, and these post circles appear to have been rebuilt multiple times. A sixth mound (Mound D) was added to the complex by people of the Coles Creek culture about 1,700 to 2,000 years later.

Advertisement

Poverty Point is exceptional not only because of its unique earthworks and because its builders relied on wild foods, but also because of its artifacts. The site is located in a naturally rockless environment, yet the residents shaped and used many tons of imported stone and minerals for tools and personal items (ornaments). The imports, which included copper, galena, soapstone, chert/flint and iron ores, like hematite and magnetite, came from up to 1,000 miles away. The people of Poverty Point also used the local soil to produce shaped “cooking balls” (aka Poverty Point Objects), figurines, pipes and a small amount of pottery. They very likely had a diverse assortment of wood and bone tools, too, but those materials did not preserve in Poverty Point’s acidic and sometimes-wet, sometimes-dry soils.

A common question during and after the World Heritage nomination process regarded how the inscription would impact the site. Would the state of Louisiana cede ownership and/or management of Poverty Point to the U.S. National Park Service or to the United Nations? The answer was and remains “No.” This remarkable archaeological site is owned by the state and is managed for the public by the Louisiana Office of State Parks, with no outside interference. The Louisiana Archaeological Survey and Antiquities Commission is responsible for granting permission to conduct archaeological research at the site.

1: LiDAR map of Poverty Point showing six earthen mounds (Mounds, A, B, C, D, E and F) and six nested, C-shaped, earthen ridges surrounding a huge leveled, 43-acre plaza. Data courtesy of FEMA and the state of Louisiana; distributed by “Atlas: the Louisiana Statewide GIS,” LSU CADGIS Research Laboratory, Baton Rouge.

2: Copper artifacts at Poverty Point. Photo by Jenny Ellerbe.

Archaeological Research

Since inscription, archaeologists from several universities, including Minnesota State University Moorhead, Mississippi State University, Binghamton University (New York) and Washington University in St. Louis, have joined with the Poverty Point Station Archaeology Program to conduct research. Progress is slow, often taking the form of baby steps as archaeologists test hypotheses and build on previous knowledge, one bit of data at a time.

In the field, methods that produce the least disturbance — such as LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), which allows creation of detailed topographic maps of the landscape, and magnetic gradiometry, which detects slight changes in the magnetic field as researchers walk across the ground — are preferred, although soil coring and excavation also are used. For example, a combination of LiDAR and magnetic gradiometry mapping led to a new appreciation for a low ridge, called the Mound E Ridge, that runs from Mound E into the plaza. Soil cores demonstrated that it was a constructed ridge, but very different in structure and composition from the C-shaped, nested, ridges that comprise the iconic architecture of Poverty Point. No artifacts were recovered in the cores, and there was no midden that would provide evidence for habitation; the soils were very “clean.” Tiny pieces of wood charcoal were recovered from the base of the ridge and natural soils underneath. When submitted for radiocarbon dating, they agreed that the Mound E Ridge was built sometime after 1440 B.C.E., early within a proposed “building boom” at Poverty Point.

Recent research on different kinds of artifacts has emphasized compositional analysis to identify the sources of the materials. For example, there are 196 fragments of copper among the artifacts from Poverty Point. Some pieces are in the form of beads, while others are rods, flat sheets, unshaped “chunks” and a single plummet.

Advertisement

The copper was long believed to have come from the Great Lakes area because there are copper deposits close to the Earth’s surface that were mined prehistorically. This idea had never been tested, but it was simply accepted as truth. A sample of six copper artifacts was selected, analyzed for its trace element composition by Mark Hill of Ball State University and Hector Neff of California State University, Long Beach, and compared to copper sources from the Great Lakes, the Appalachian Mountains and other areas. The results indicated the Poverty Point samples are most similar to copper sources in the Appalachians. This does not mean, however, that all of the copper came from the Appalachians. There could be more than one source. A larger sample of 24 more pieces has been submitted for analysis, but those results are not yet known.

Other kinds of investigations, like use wear analysis (to determine how a tool was used by looking at the tiny bits of damage resulting from its use) or microartifact analysis (to identify tiny objects that inform on activities that took place on floors and other special surfaces), also are conducted. For example, researchers at Mississippi State University have analyzed more than 1,000 microartifacts in soil samples taken from a flat, thick, compact, light-colored deposit suspected to be a house floor. They found bone, charcoal, burned sandstone and tiny chips, or flakes, of many different kinds of stone; such “microflakes” are produced when somebody makes or uses a stone tool. This range of materials is consistent with expectations of a house floor.

Occasionally, a more exciting discovery occurs, such as the finding of a previously unknown mound. Mound F is located within the park, but outside the area where staff and visitors normally go. It is a small mound (roughly 90 feet in diameter and 5 feet tall) built on the eastern edge of Macon Ridge, overlooking Bayou Maçon and the Mississippi River floodplain. Based on radiocarbon dates, it appears to be the last mound associated with the Poverty Point culture. Like the other mounds at Poverty Point, there are no human burials or caches of fine artifacts in the mound or evidence for buildings, like temples, on the top. Archaeologists don’t yet know its purpose, but its construction would have brought people together in a shared public effort.

With support from the Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism and permission from neighboring landowners, the Poverty Point Station Archaeology Program has launched an archaeological study of the territory beyond the state property boundaries. Although the primary goal is to learn how the people of Poverty Point used the broader landscape, the remains from other cultures are documented as well. Archaeologists hope to learn, for example, if people lived in hamlets or small villages outside of the monumental center and how they used the diverse environments around them for acquiring different kinds of plant and animal resources.

1: Mound F at Poverty Point. Photo by Jenny Ellerbe.

2: David Griffing shows how to make a Poverty Point Object for an earth oven cooking demonstration.

Interpretive Programs

In the five years since becoming a World Heritage Site, the Office of State Parks has documented a rising level of visitation at the park, with the number of out-of-state visitors showing steady year-after-year growth. The state anticipated that visitation would increase slowly following inscription given the site’s remoteness and its low name recognition; this is a good thing, as it allows the opportunity to monitor the site for tourism-related impacts and will permit management changes to protect this remarkable archaeological resource at the first signs of damage.

The park has an on-site museum, with an introductory video and artifact displays, and there is a Junior Ranger program for kids. Interpretive rangers offer tram tours around the site four times daily, Wednesday through Sunday, from March 1 to October 31, or visitors can elect to explore on their own with a self-guided hike or driving tour.

In addition to themed ranger-guided hikes (night hikes, bird-watching hikes, edible-plant hikes), the Office of State Parks also offers an increasingly diverse series of demonstrations and/or staff-led activities that include flintknapping, spear-throwing with atlatls, fire starting, earth oven cooking, pottery making, acorn cooking, sock moccasin making, tool use and artifact identification. These special programs are typically scheduled on Saturdays, twice a month.

We encourage you to visit Louisiana’s World Heritage Site. Poverty Point is open from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., 362 days per year (closed on Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year’s Day). You can learn more at www.PovertyPoint.us or look for Poverty Point World Heritage Site on Facebook.

Diana M. Greenlee is the station archaeologist at the Poverty Point World Heritage Site

Advertisements