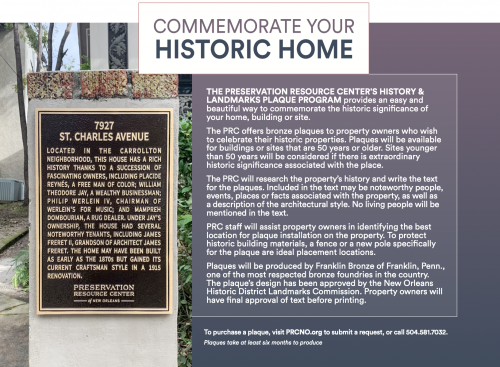

This story appeared in the February issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

By Stephanie Bruno & Maryann Miller

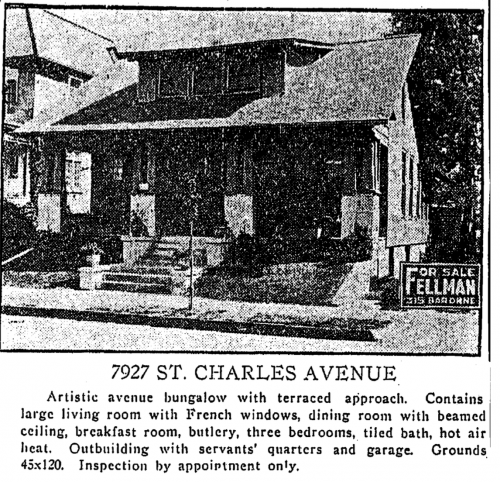

When the stucco cottage at 7927 St. Charles Ave. was offered for sale by Fellman Realty in 1921, it was described in the newspaper ad as an “artistic avenue bungalow.” But what no newspaper ad could express was the series of fascinating owners who have lived at the address over the years and have been the source of its artistic character.

It is difficult to ascribe a “built” date to the home at 7927 St. Charles Ave., according to architectural historian and author Robert J. Cangelosi Jr.’s book New Orleans Architecture: Volume IX: Carrollton. The early maps of the area are inconclusive, and the appearance of the home may have changed over the years. Although it appears to be a bungalow built about 1915, it may well be a considerably older house that was renovated. Adding to the mystery is the fact that city directory records date the house to 1870 by placing Dr. Don Carlos Case and his wife, Martha Ann Thomas, on St. Charles Avenue between Washington (today’s Fern Street) and Short Street and at the northeast corner of St. Charles and Short.

The 1883 Robinson Atlas shows a square footprint of a building more or less in the center of two large lots, straddling the lot line. The 1908 Sanborn Fire Insurance map shows a house having the general footprint of a cottage with a front porch, but located on the east side of what was shown as two lots on the 1883 map. The 1937 Sanborn map shows a house with a rectangular footprint, a porch on the front and a partial porch on the rear. There also is an outbuilding in the rear, as well as a structure to the west of the subject house. Moreover, a long narrow house, likely a shotgun, was shown adjacent to this property on the 1908 Sanborn map, but the shotgun had vanished by 1937. The subsequent vacant lot became a part of the parcel on which 7927 St. Charles Ave. sits, and today that space is the garden of the current home, although research is not clear about when this occurred.

By 1921, when the Fellman Realty ad was published, the house likely looked on the exterior much the same as it does today. It has a Craftsman-style side-gabled, terracotta barrel tile roof, punctuated by a low and wide dormer. The full-width front gallery is shaded by the roof (not a roof extension), which is supported by two pairs of box columns in the middle and a cluster of three columns at each end of the porch. Although the central pairs of columns rest on the porch decking, the outer trio of columns rest upon a stucco and brick pedestal that extends forward of the edge of the porch.

Windows adhere to the Craftsman practice of having a different number of panes on the top sash and on the bottom. In the case of the paired windows on the facade, the configuration is “six over one,” meaning six rectangular panes of glass in the top sash and a single large pane on the bottom. Similarly, the pairs of windows in the dormer that appear on both sides of the recessed central decorative window feature nine small square panes of glass over a single pane (or nine over one).

The Fellman ad mentions a “terraced approach” about the levels of steps, which are covered in flat terracotta tiles that ascend from the sidewalk to the front gallery, where the tiles are used as flooring. Stucco covers the house, and there is a shallow bay on the left side.

The Fellman ad also describes the interior as having a living room, dining room with a beamed ceiling, breakfast room, butlery, three bedrooms and servant quarters in a detached building. Sometime after 1921, the attic was finished out and today holds additional bedrooms and a bath for a total of six, as well as an extra bath.

When the current owners acquired the property in 1990, they made changes to the exterior and interior. The most dramatic was the move of the entry assembly (a handsomely carved entry door flanked by sidelights and having a transom atop) from the center position on the facade to the far right, to make better use of the vestibule/foyer inside the house. The couple clarified the interior floor plan and installed a pair of stained-glass windows in the dining room that appear in the shallow bay on the left or western side of the house. They also installed a side entrance on the east or right side of the house next to the driveway and added a carport. The full-width rear porch was created by the current owners and replaces a set of narrow steps that previously led from the rear door of the house to the ground.

The fanciful cast iron railing on the front, rear and side porches can be credited to the current owners, as well as the insertion of vertical panels of cast iron in a vine motif between the columns on the front porch.

In the lot to the right of the house, the owners created a garden complete with a shady pergola. At the rear of the lot stands an outbuilding that may have once been a garage, but which was converted by today’s owners into the family game room. It has antique wood paneling and an open ceiling that reveals wood structural members, and it benefits from a row of stained-glass windows on the rear wall.

The New Orleans Assessor’s website calls the garden lot at 7927 St. Charles Ave. (Square 72, Lot A, 30 feet wide by 155 feet deep) as a separate lot of record. The house is sited on a lot at 7929 St. Charles Ave. that measures 45 feet wide by 120 feet deep (Square 72, Lot 3 and half of lot 2). The current owners, however, refer to the main house’s address as 7927 St. Charles Ave.

Originally, the house was situated on lots 1, 2 and 3, each measuring 30 feet wide. It is not clear from the research at what point in time Lot 1 and half of Lot 2 were subdivided and separated from the original property, but the house at 7933 St. Charles Ave. was built in 1915 on those lots (per Cangelosi’s research), establishing a rough timeline for the subdivision.

Advertisement

The Case Family

The family of Dr. Don Carlos Case was the first to be listed as living at the northeast corner of St. Charles Avenue. Dr. Case was a native of New York, born in 1819, and a physician who, according to his obituary, was sympathetic to the Confederacy.

The family of Dr. Don Carlos Case was the first to be listed as living at the northeast corner of St. Charles Avenue. Dr. Case was a native of New York, born in 1819, and a physician who, according to his obituary, was sympathetic to the Confederacy.

He and his wife, the former Martha Ann Thomas of Missouri, moved to New Orleans in 1865 and took up housekeeping on Prytania near Delachaise streets. By the time of the 1870 census, however, they were living in Carrollton — in Jefferson Parish at that time — at the corner of Short Street and St. Charles Avenue. Their place of residence was confirmed in the city directories from 1872 through 1875.

Records indicate that the Cases purchased three lots (presumably Lots 1, 2 and 3, each 30 feet wide) at that location in November of 1875, but according to the 1870 census, the couple already owned their residence. (It was valued at $4,500.)

In 1878, the family (Don, Martha and their children Charles Theodore, May and Fanny) moved to Ocean Springs, Miss. When Dr. Case died in 1885 (or 1886, the records conflict), he was much lauded by the locals, who praised him for caring for the poor. He also was credited with treating skin cancer by directing light to lesions using cobalt glass.

In 1881, the Cases sold 7927 St. Charles Ave. to Jane Eliza Hickok, widow of Dan Hickok, the “genial, bluff and jolly” proprietor of the Carrollton Hotel. The Hickoks were practically neighbors of the Cases; they lived just around the corner on Short between St. Charles and Hampson Street, according to the 1878 to 1880 city directories. Perhaps that is why Jane Hickok bought the house on St. Charles Avenue after her husband died in 1880 at the age of 70.

Daniel Starr Hickok was a larger-than-life character. His first career was as a steamboat captain, which is why he is referred to in the newspapers of the era as “Capt.” Dan Hickok. When Hickok and Jane Eliza moved to New Orleans from Connecticut about 1847, he “abandoned steamboating” in favor of becoming a hotelier. His first venture was the Lake House on Lake Pontchartrain, which became “famous not only for its bibulous and substantial entertainments but for the wit and humor of the host… a fellow of infinite comicality.” In 1867, he became the owner of the Carrollton Hotel, which he renovated. Hickok stopped at nothing to please and delight his guests and went so far as to serve “baked monkeys… straight from South America” for lunch on Sundays.

After Jane Hickok died in 1885, the property on St. Charles Avenue reverted to the Case family, as the decedent named Don Carlos Case and his brother, Theodore, co-equal legatees of her estate. And because Dr. and Mrs. Case had both died by that time, their children — Charles, May and Fanny — took possession of their father’s half. It isn’t within the scope of this report to determine why Jane Hickok left her estate to the Case brothers, but it adds yet another layer of mystery to the history of the house.

Advertisement

The Cases sold the property in 1895 to Placide Francois Reynes about a year before Reynes married Lenna Ethel Scott of Michigan. Many records say that he was born in New Orleans in 1857 to Constant (Constantino) Reynes and Mathilde Louise Josephine Richeux, although research on Ancestry.com asserts he was born instead in Tampico, Mexico. And although the date of his birth is not in question, there are other aspects of his birth and early life that are.

The Cases sold the property in 1895 to Placide Francois Reynes about a year before Reynes married Lenna Ethel Scott of Michigan. Many records say that he was born in New Orleans in 1857 to Constant (Constantino) Reynes and Mathilde Louise Josephine Richeux, although research on Ancestry.com asserts he was born instead in Tampico, Mexico. And although the date of his birth is not in question, there are other aspects of his birth and early life that are.

The earliest records say that Reynes was mulatto or Black. Later documents say he was White. There is also a christening that took place in Mexico in May 1859 of a boy having his name (Placido Francisco Reynes) and the names of his parents. Other documents substitute the name “Relf” for “Reynes.”

A woman on Ancestry.com claimed: “He was of mixed race. In the period immediately prior to the Civil War, free people of color began to see their rights and privileges curtailed and suffered increased oppression, so many escaped to Tampico, Mexico, for the duration of the war. It was during this period that Placide was born in Tampico, so we can assume that his family was among those to have emigrated due to political oppression.” She also explained that Relf is the name of his mother’s second husband.

If she is correct that Reynes was a free man of color who passed for white, that lends credence to a phone call the current owners received 15 years ago from a woman claiming to be a descendant of Placide Reynes. She said that he was “mulatto” and that he kept two households — one in the French Quarter for his “Black family” and one on St. Charles Avenue for the white family. If she was indeed a descendant of Reynes, she must have been a member of the Black family, as Placide and Lenna Ethel Scott Reynes had no children.

Reynes was nearly 40 when he married the much younger Scott. They honeymooned in Bay St. Louis, Miss., before returning to St. Charles Avenue, where, according to the 1900 census, they lived with Placide’s mother Mathilde, his brother George and George’s wife and daughter.

On Jan. 7, 1902, Reynes left for work and arrived at Hart’s Loan Office at 8 a.m. as was his custom. He carried on a conversation with the jeweler and the porter before heading to the rear of the office and behind a screen where he worked. He continued the conversation from there, but no sooner had Reynes finished playfully bantering about a ship at anchor in New Orleans, than his two companions heard a gunshot and the sound of a falling body.

The popular, social, and accomplished (fluent in three languages) Placide Reynes had shot himself in the right temple. His death was judged to be a horrific accident, for “what man contemplating so horrible a deed would take notice of so ordinary a conversation when he was in the act of taking his own life?”

The family household was shattered. In Reynes’ will, he bequeathed photographic equipment to a member of the Photography Club, which he helped found, and his “stereopticon and lantern slides” to a friend. He directed that his wife (they were married for six years before he died) and mother divide equally the proceeds from the sale of the house and his personal effects (“share and share alike,” he urged). To his brother George, 10 years his junior, he left his watch.

The wife and mother wasted no time in liquidating the household. About three weeks after Reynes’ death, “parlor goods, piano, pictures, large lot of fine books, dining room furniture, kitchen outfit, bathtub, bath heater, ornaments” and a “pair of Japanese fantail goldfish” were auctioned off, “on account of relinquishing housekeeping.” In May 1902, the house and the land (three lots each measuring 30 feet by 120 feet) were offered at auction. Charles Durr, a “saloonkeeper” was the winning bidder at $3,450.

Durr owned the property just two years before selling it in 1906 to William Theodore Jay, an entrepreneur and cotton broker who made a fortune in lumber across the lake in Madisonville. That is where he built his first landmark, the 1885 Otis House. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1999.

There is nothing indicating that Jay ever lived at 7927 St. Charles Ave., although in the Carrollton book, Cangelosi attributes the home’s Craftsman bungalow appearance to a renovation undertaken by Jay in 1915. Instead, it seems that Jay maintained it as a rental property.

Jay and his family occupied a far grander home: 2 Audubon Place. Designed by architects Toledano and Wogan, that home, built in 1908 and originally in unpainted red brick, occupies a prominent lot on the city’s most exclusive (private) street. It was designed to have formal entries on both St. Charles Avenue and Audubon Place, so that Jay could have the Avenue address he coveted but still abide by Audubon Place’s strict rules.

To say that Jay and his wife, the former Lavinia Vosburg, were society darlings during the years between 1907 and 1917 when they lived on Audubon Place would be a gross understatement. They were in the society pages practically every week, with reports of their South American travel, teas for their daughter Minter, luncheons for various clubs, bridge parties, dances, holiday cotillions and more. They spared no expense and developed a reputation for regally entertaining guests.

Meanwhile, at the rental property at 7927 St. Charles Ave., there was a series of interesting tenants, including Nils Herlitz, vice president of the Swedish Iron and Steel Corp.; Eleanor Mitchell, librarian; and Dudley O’Dowd, division superintendent of the Carrollton Streetcar Barn.

By far, however, the most prominent renters during the Jay era were James P. Freret II, his brother, Louis Emile Freret, and their sister, Ada Marie Freret. During their residency in 1910 and 1911, James Freret was the assistant secretary of the Southern Cypress Manufacturers Association; Emile Freret was a real estate agent; and Ada Freret was the principal of the Société Française du 14 Juillet School in the French Quarter. Ancestors included their uncle James A. Freret, the renowned architect, and their great uncle William A. Freret, mayor of New Orleans from 1840 to 1842.

Jay sold the house at 2 Audubon Place in 1917 and the home at 7927 St. Charles Ave. in 1919. The former was sold for $60,000 to Samuel Zemurray, owner of United Fruit Company, known as the “Banana King.” (Zemurray’s wife ultimately donated the house in 1965 to Tulane University to use as its president’s house.) Jay sold the rental property for $6,000 in 1919 to Dr. Cornelius A. M. Dorrestein, a gynecologist from Holland who served on the board of the Whitney National Bank.

When Jay died in 1948 at the age of 92, his estate was valued at $110,000, about $1.2 million in today’s dollars.

Dr. Dorrestein died of a heart attack at 7927 St. Charles Ave. in 1935, after which it was offered for sale for $9,000. In a 1938 ad, it was described as a single bungalow with a finished attic, having 75 feet of frontage on the avenue. This indicates that the original three lots measuring 30 feet wide each had been subdivided into two 45-foot-wide lots, the westernmost of which was used for the 1915 construction of the house at 7933 St. Charles Ave. It also indicates the 30-foot-wide lot where the single shotgun once stood had been added to the parcel.

Mampreh Dombourian, an Armenian rug dealer, bought the house in 1939 from the Dorrestein estate and lived there with his large family for seven years before selling it for $27,500 in 1946 to Mayme Kelly, wife of Evans O’Brien, general manager of Werlein’s. In turn, Mayme Kelly sold the house to Philip Werlein IV in 1948 for $30,000.

Advertisement

Werlein was a descendant of Philip Werlein, who came to the United States from Bavaria in 1831. After he left Vicksburg for New Orleans in 1850, Werlein created a music empire. His store, which specialized in selling pianos, and his music publishing business grew to be one of the largest in the south. In fact, Werlein was the only music publisher in the pre-Civil War south recognized by the Board of Music Trade and given membership. Werlein also was the first to publish the sheet music to “Dixie” and was forced into temporary retirement in New Iberia after refusing to swear an oath of allegiance to the Union during the Civil War.

Werlein was a descendant of Philip Werlein, who came to the United States from Bavaria in 1831. After he left Vicksburg for New Orleans in 1850, Werlein created a music empire. His store, which specialized in selling pianos, and his music publishing business grew to be one of the largest in the south. In fact, Werlein was the only music publisher in the pre-Civil War south recognized by the Board of Music Trade and given membership. Werlein also was the first to publish the sheet music to “Dixie” and was forced into temporary retirement in New Iberia after refusing to swear an oath of allegiance to the Union during the Civil War.

Werlein returned to New Orleans in 1865 and resumed business, first on Baronne Street, then on Camp Street, before finally landing at 605 Canal St., where Dickie Brennan’s Palace Cafe is located today. Although the family sold off its publishing business in 1940, “Werlein’s for Music” was a landmark destination for instruments until the latter part of the 20th century. Kid Ory, Fats Domino and Louis Armstrong are just some of the performers who bought their instruments at Werlein’s.

Philip Werlein IV became chairman of the company, then general manager, before being elected president in 1953. Post-World War II prosperity made it possible for him to expand the business to 10 stores. In 1983, he was succeeded as president of the company by a cousin but was again elected chairman of the board.

When Werlein died at 71 in 1986, he left a daughter, Anatasia “Bitsie” Werlein Mouton (spouse of architect Grover Mouton), and a son, Philip Werlein V. His wife Anatasia Schlueter had died in 1979, and his son Theodore Thomas “Teddy” Werlein, had died in 1971 in a car accident on the Causeway bridge when he was just 20. In 1988, Werlein V and Mouton were judged to be in possession of their father’s estate, including the property at 7927 St. Charles Ave. They sold the property in June 1990 to Jacques and Clara Binet Creppel.

Jacques Jules Creppel, a military pilot, and Clara Binet, an ardent preservationist, met at Louisiana State University. They married in 1957. They are the parents of six children.

Jacques Jules Creppel, a military pilot, and Clara Binet, an ardent preservationist, met at Louisiana State University. They married in 1957. They are the parents of six children.

The couple bought 7927 St. Charles Ave. in 1990 and made changes to improve its livability. But the St. Charles Avenue house is not the only historic building they have owned. In June 1980, they bought the Columns Hotel, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, for $425,000 and fully restored it. The couple sold the Columns — also known as the Simon Hernsheim house — in 2019 for an undisclosed sum of money.

The Woodland Plantation in Plaquemines Parish is a circa-1834 historic property, also on the National Register, that the Creppels and their son Foster bought at auction in 1998. They spent two years rescuing it from extreme neglect, repairing and restoring it, before it became a bed and breakfast. Several historic buildings, including a chapel, were moved to the 50-acre site in subsequent years. If Woodland Plantation looks familiar, it could be because the building was featured on the label of Southern Comfort.

Although New Orleans remains their home, the Creppels spend a number of months each year in Nova Scotia in a historic house they moved to a picturesque location on a low bluff overlooking a scenic river. Among the aspects of living in Nova Scotia that they treasure is the fact that nearly everyone plays a musical instrument.