This story appeared in the February issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

Rashida Ferdinand grew up in the Lower Ninth Ward and can recall running errands and shopping along St. Claude Avenue in the 1980s. When she looks down the street today, she sees many of the same buildings, but the vitality has been drained from this once-lively corridor. The scene includes litter strewn across the neutral ground, vacant shop fronts and blight.

But that’s not all she sees: “I see this great opportunity for a diversity of types of businesses,” Ferdinand said.

As the driving force behind the new St. Claude Avenue Main Street program, Ferdinand has embraced a proven model that combines historic preservation with economic development in small towns and, increasingly, urban communities, around the nation.

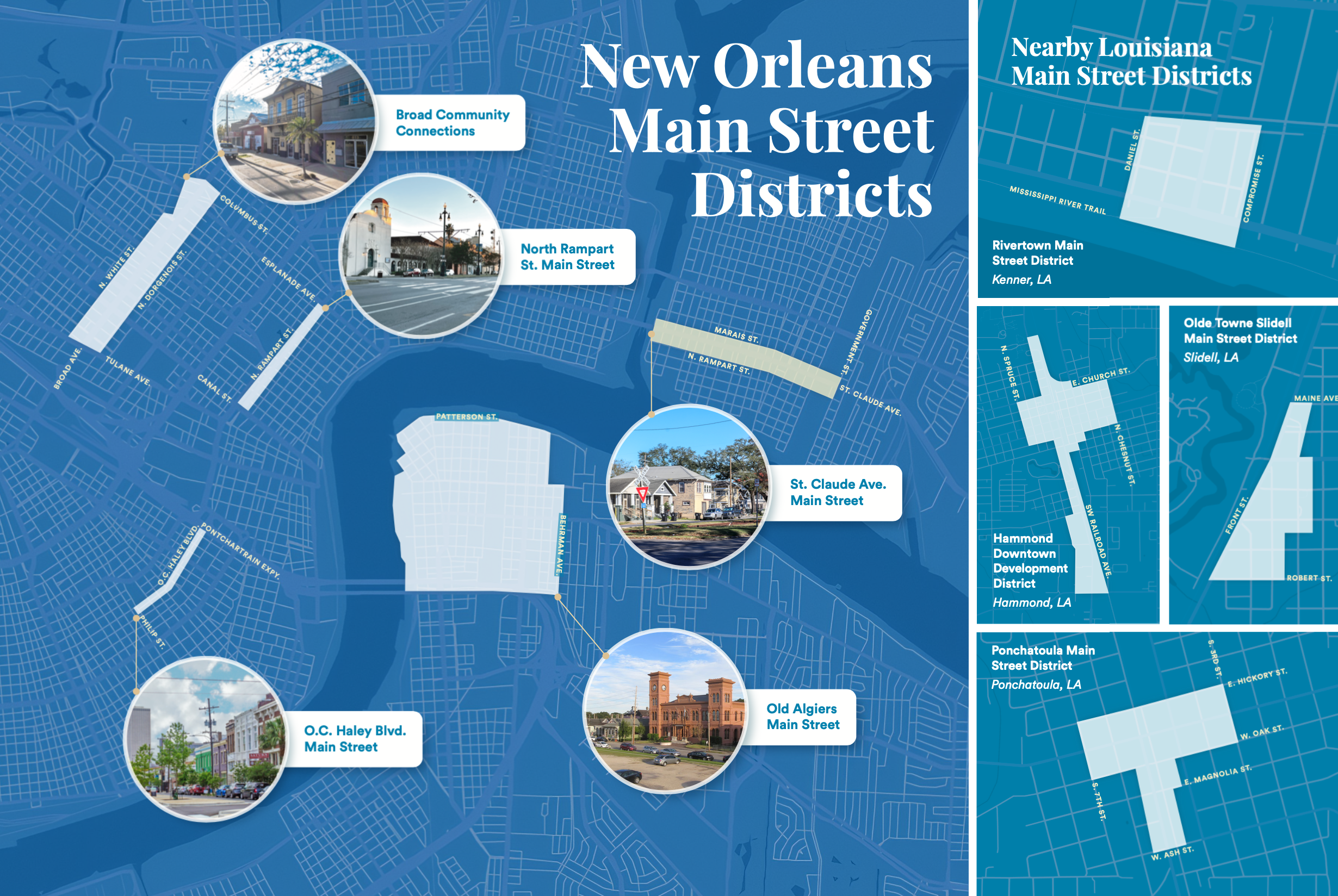

“Main Street started with a small-town focus exclusively,” said Ray Scriber, Louisiana Main Street director for the state’s Division of Historic Preservation. “Then, other states had urban Main Streets. After Hurricane Katrina, we started Main Streets in New Orleans.”

The Main Street model was developed in response to runaway suburbanization and the rise of big box retail, which hollowed out downtowns, leaving century-old storefronts vacant. The National Main Street Center — today known as Main Street America and a subsidiary of the National Trust for Historic Preservation — opened its doors in 1980. Louisiana created a companion program four years later.

In 2021, Louisiana had 25 accredited Main Streets, most with a dedicated staff member and a sponsoring local not-for-profit organization. Nationwide, there are more than 1,200 participating communities. Five of the state’s accredited Main Streets are located in New Orleans.

The St. Claude Avenue Main Street in the Lower Ninth Ward was officially accepted into the program in November 2021. “From a Main Street perspective, the organizational structure and the Main Street four-point approach can be implemented in a small town or an urban district,” Scriber said. Those four points are: organization, design, promotion and economic vitality.

Through detailed market analysis and community engagement, each Main Street identifies one or more “transformation strategies” to attract a particular customer segment, fill a need or create a unique destination. In the case of the St. Claude Avenue Main Street, proponents aim to transform not only the street but the lives of people who live and work there.

When Ferdinand returned to New Orleans in 2004 as a young adult, she chose to make her home in nearby Holy Cross. “I felt this was a place where I could buy a home and be comfortable in. It was close to downtown, and there was green space. I like being close to the river and the water.” The Lower Ninth Ward had changed since her childhood, but it still had high rates of homeownership and civic pride. It would soon be forever reshaped, as would she.

Advertisement

After Hurricane Katrina struck in 2005, Ferdinand was able to return to her home in 2006. “I wanted to do work to restore this area,” she said.

Ferdinand founded Sankofa Community Development Corp. in 2008 with a focus on health equity. A fresh produce stand, food pantry, urban farm and wetland park followed. In December 2021, the organization broke ground on a new Fresh Stop Market, celebrating with the sounds of the G.W. Carver High School marching band. At the corner of Forstall Street and St. Claude Avenue, the new market will replace an open-air farm stand with a permanent storefront offering longer hours, cooking classes and a small cafe counter.

“We’re thinking of a health-centered development model, thinking of what it means to have a healthy neighborhood,” Ferdinand said. “The Fresh Stop Market project complements the objectives of the St. Claude Avenue Main Street by “making our avenue welcoming and a place that people want to come visit and learn about who we are in this community.”

Click to expand images

Population decline shuttered neighborhood-serving businesses like dry cleaners (left), but as the Lower Ninth Ward rebounds, nonprofits and entrepreneurs are betting on St. Claude Avenue (above). Photos by Liz Jurey.

Less than a block away, another entrepreneur and Ninth Ward native is helping bring her own take on fresh to the neighborhood: a rainbow of cut flowers. “I carry a huge variety because I want them to know all of these things exist — peonies, orchids. … It sets a tone and has allowed Black people to say they’re worth experiencing fresh blooms, and they can afford it,” said Brandi Charlot, who opened the storefront iteration of her business, B Lucid Floral, on St. Claude Avenue in 2020.

“During the pandemic, I decided to open the business to let people experience flowers,” she explained. “It was actually a great time.” Stuck at home and tired of grim news, people were looking to plants and flowers for moments of beauty and serenity.

Widespread protests against racial injustice in 2020 also invigorated a movement to support minority-owned businesses. Charlot’s clever use of social media and a stellar reputation with her mainstay corporate clients helped spread the word about her new venture in spite of her modest marketing budget.

Advertisement

A licensed florist for five years (a credential issued by the Louisiana Horticulture Commission with no parallel elsewhere in the United States), Charlot entered the field as an event planner. “I really enjoyed that (floral design) side of it,” she said. “I realized that I actually had a gift, so I began to educate myself. I studied in New York … then I came home and went to work.”

The “Flower Bar” is housed in a bright blue, Arts and Crafts-style double that her family purchased years ago. Like many properties along this historic street, the building has alternated between residential and commercial uses through the years. Her father’s likeness hangs behind the cash register wearing a baseball cap that trumpets “Generational Wealth.” The artwork is not only an homage; it is a message of empowerment for her customers.

Charlot hopes that the new Main Street program will enable more Lower Ninth Ward families to benefit from their neighborhood’s legacy. She was able to build out a retail space that filled a void in the community, and now she is optimistic that the Main Street program will help meet other needs.

“I get to look out the window and see what we’re missing,” Charlot said. Beautification, plantings and signage along St. Claude Avenue can inspire more entrepreneurs to follow her example, she said. “Once they start to beautify the area, it will attract other business owners and make people want to come into the area — and the development builds.”

Click to expand images

Brandi Charlot in her flower shop, B Lucid Floral, on St. Claude Avenue. Photos by Liz Jurey.

There are particular challenges to revitalizing historic commercial corridors within a larger city, especially in communities of color that have endured redlining, segregation and disinvestment. In 2017, Main Street America launched its Urban Main program to provide tailored resources to historically under-resourced communities.

According to the New Orleans Data Center, average household income in the Lower Ninth Ward is half that of Orleans Parish as a whole. But that’s only part of the story. Gutted by the flooding caused by the levee failures after Hurricane Katrina, the population of the Lower Ninth Ward today is approximately half of what it was in 2000.

In a promising sign, the area’s population has increased faster than the parish average during the past decade. While other areas of the city (Lakeview, Gentilly) had substantially rebounded from Katrina losses by the 2010 census, the Lower Ninth Ward was slower to recover. But the 2020 census shows evidence that the population there is slowly growing. That is a welcome trend for neighborhood-serving businesses, such as hair stylists, restaurants and auto mechanics, all of which can be found along St. Claude Avenue.

The new St. Claude Avenue Main Street envisions coordinated investment in housing — both repairs to the surviving historic housing stock and infill development on a smattering of vacant lots — as well as support for start-ups. Representatives from the New Orleans Redevelopment Authority and Jericho Road Episcopal Housing Initiative serve on the new Main Street steering committee alongside representatives from the New Orleans Business Alliance and the Urban League. Also participating are city agencies and numerous community-based organizations, including the Leona Tate Foundation for Change, a driving force behind the redevelopment of the former McDonogh 19 school building at 5909 St. Claude Ave. to include senior housing and an interpretive center.

The steering committee was assembled during what Louisiana Main Street calls the Lagniappe phase, during which time interested communities receive coaching on the Main Street approach and begin assembling the information needed to apply for the designation. “One of the reasons why I was interested in the program is that there was a support structure there. Beyond an idea and a model, there was staff there to support it,” Ferdinand said. She was invited to a Main Street workshop in Crowley and left with new understanding and enthusiasm for a program that has created more than 14,000 jobs and 3,000 new businesses across Louisiana.

Transformation won’t come to St. Claude Avenue overnight. Plans call for hiring a full-time Main Street director in 2022; that person will implement a $10,000 grant from the New Orleans Business Alliance, conduct community outreach and survey the corridor to find buildings or parcels primed for investment. The director and steering committee will have the support of the Louisiana Main Street program and a peer network. “In the Lower Ninth Ward, they have such a good plan in place,” Scriber said. “We’re looking forward to the opportunity to help them and partner with them on that.”

Nathan Lott is PRC’s Policy Research Director and Advocacy Coordinator.

Abandoned storefronts invite vandalism and deteriorate steps away from well-maintained houses and historic buildings adapted for commercial use. The blend of homes and businesses along St. Claude Avenue coincides with a diversity of building styles and eras. Photos by Liz Jurey.

Advertisements