This story appeared in the June issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

Charting the Plantation Landscape from Natchez to New Orleans, a new book from LSU Press’ Reading the American Landscape series, presents a fascinating, multi-faceted view of the broadly interpreted plantation landscape. Seven contributing essayists pierce the veil of mansion architecture and antebellum living to examine the political and social currents, health perils and medical care, artistic representations, economics, labor hierarchy and the reality of the emancipation struggle — all within the cultural and agricultural constructs of the “plantation landscape.”

Charting the Plantation Landscape from Natchez to New Orleans, a new book from LSU Press’ Reading the American Landscape series, presents a fascinating, multi-faceted view of the broadly interpreted plantation landscape. Seven contributing essayists pierce the veil of mansion architecture and antebellum living to examine the political and social currents, health perils and medical care, artistic representations, economics, labor hierarchy and the reality of the emancipation struggle — all within the cultural and agricultural constructs of the “plantation landscape.”

“The benefit of considering plantations as landscapes — built, designed, experienced, etc. — is that from the onset we are less focused on the particular and more attentive to the relationship(s) of those particulars,” writes the book’s editor Laura Kilcer VanHuss. “Fundamentally, the book is a response to the romanticization and incomplete narratives that have traditionally dominated plantation interpretation, and gives us a chance to look at these spaces more holistically, and therefore more critically.”

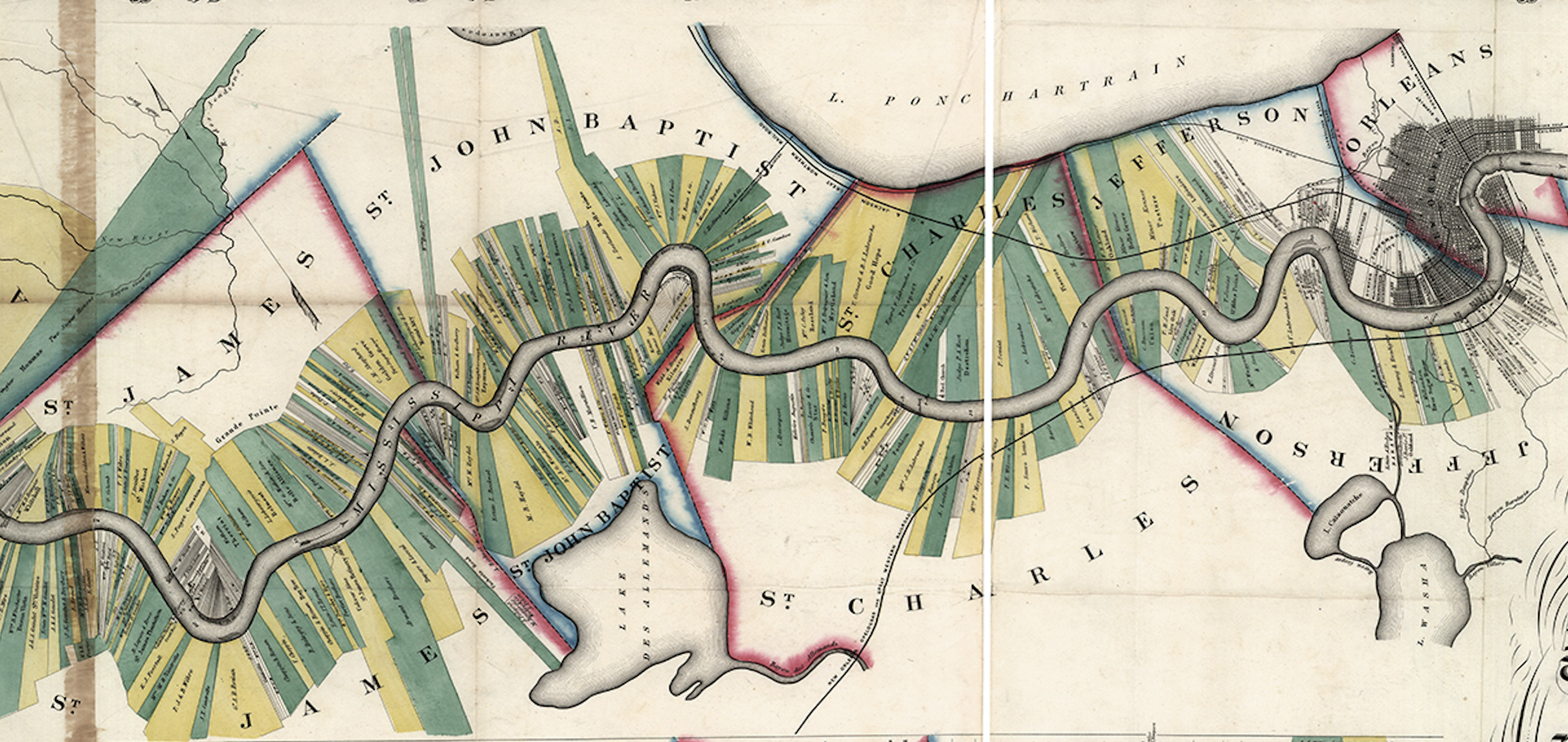

The book’s foundation is Norman’s Chart of the Lower Mississippi River, one of the 19th-century South’s most famous maps, created by artist and surveyor Marie Adrien Persac, who depicted more than the geography of the agro-industrial corridor. Taking liberties in representing a land teeming with prosperity, Persac’s chart concealed the “enslaved and exploited laborers whose work powered the plantations,” as the book’s description notes. As a result, the map helped to create a plantation myth that evolved through tourism and productions such as Gone with the Wind. Missing were the hard realities of the human bondage at the center of sugar and cotton production enterprises.

Through the seven essays, the scholarship of Charting the Plantation Landscape takes a more serious look at those realities. From Christopher Willoughby’s chapter, we learn of the prevailing medical opinion that people of African descent carried inherited immunity to malaria and yellow fever — an opinion that was interpreted as a medical defense of slavery. Paradoxically, doctors developed novel expertise in treating occupational injuries due to the demands of high crop yields and mechanization of production, notably in the area of women’s reproductive health.

William Horne’s essay discusses emancipation and how relationships formed in slavery became the basis of African American political grassroots organization. In spite of the Emancipation Proclamation, it was necessary for the Army to issue General Order No. 3 to force the freeing of the enslaved. (The order was delivered more than a month after the end of the Civil War and two years after the original issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation. The event is now celebrated as Juneteenth.) Then arose the Black Codes, created to limit the mobility and civil rights of Black people. Woven into Horne’s essay is the history of violence, including the Mechanics Institute and the Colfax Massacres, as well as the ensuing reaction, resistance and reform.

In the immediate post-Civil War era, the plantation landscape as an art genre mostly disappeared, as detailed in Jochen Wierich’s “After Persac” essay. While photography accompanying southern travel accounts focused on city views, gardens and pastoral landscapes, artist William Aiken Walker provides the exception with his paintings of Old South images blurring into the New South. What was the intent of Walker’s stereotypical portraits? The pictures have been described variously as a reimagining of the plantation landscape, a public fiction and visual cartoons.

Laura Blokker’s essay on architecture goes beyond descriptions of style, its evolution and construction techniques to examine both the order and dominance established by placement of the service buildings and the dwellings for enslaved individuals.

The land, the river, nature, culture and human interaction comprise the core of the story. The land settled by Native American tribes, Europeans, missionaries, Creoles, Africans and Americans reflects these cultural identities, as described by essayist Suzanne Turner. Critical also is the evolution of the land’s uses, changed forever by the 1901 discovery of oil — plantation to petrochemical. This collection suggests that, to understand this landscape, one must decipher all the imprints of its heritage.

“Charting the Plantation Landscape from Natchez to New Orleans” ($45) is available through LSU Press and local booksellers.

Advertisement