Much of New Orleans Culture — indeed, most of the human experience — derives from external influences imported via various peoples and pathways, which gradually syncretize locally to become something distinct. The city has returned the favor, exporting its own indigenous innovations worldwide, including Creole foodways and jazz.

Then there are cases of New Orleanians who went off to create great things elsewhere, which subsequently found their way back home as part of their broader national diffusion.

One such example of that cultural “re-importation” is the Romanesque architecture of Henry Hobson Richardson, a man so thoroughly associated with this distinctive style that colleagues named it in his honor shortly after his death, a rarity in architecture.

H. H. Richardson was born in 1838 on the Priestly Plantation in St. James Parish, Louisiana, now the St. Joseph Plantation in Vacherie. He grew up in a Julia Row townhouse in New Orleans and briefly attended the University of Louisiana, a predecessor of Tulane. He set off for Harvard and spent the Civil War years studying at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris before returning to establish an architectural practice in New York City.

Over the next 20 years, Richardson would develop and refine a style he initially gleaned from the medieval churches and castles seen on his European sojourns. Stout and venerable, the ancient Roman-influenced edifices exuded strength and permanence through their massive stone walls, broad semicircular arches and vaults, short columns, and fortress-like turrets and towers. Yet those stoic structures retained a romantic quality to them, appearing graceful and picture-perfect in the landscape.

That picturesque sense of romance appealed to 19th-century eyes. As the Enlightenment gave way to modernization and industrialization, Western artists and philosophers shifted away from their fascination with Classical antiquity, which helped inspire the revival of Greek architecture (Neoclassicism), and found a new muse in the aesthetics of the Middle Ages and Renaissance. The shift reflected a new spirit called Romanticism, which embraced beauty and emotionality and appreciated the picture-like qualities of the old ruins in the landscape — so much so that a “Picturesque Movement” began to affect the design of English parks and villages.

Romanticist and Picturesque tastes steered architects toward a revival of the building styles of the Middle Ages, including Italian, Gothic and Norman. These would become known respectively as Italianate, Gothic Revival and Romanesque Revival architecture. (The term “Romanesque” here did not connote ancient Rome per se but rather the Norman buildings erected after the fall of the Roman Empire. Latter-day observers of magnificently aging Roman-influenced edifices tended to “Roman-ticize” them — thus the term.

H. H. Richardson studied in Paris at a time when Romanticism and its architectural manifestations were peaking in Europe but still fairly new to the United States. He returned to a nation transformed by the late war, and the victorious North was ready for new ideas — and new construction. English Gothic and French Second Empire were all the rage, and Richardson, in partnership with his business manager Charles D. Gambrill, initially followed suit in his early work in New York.

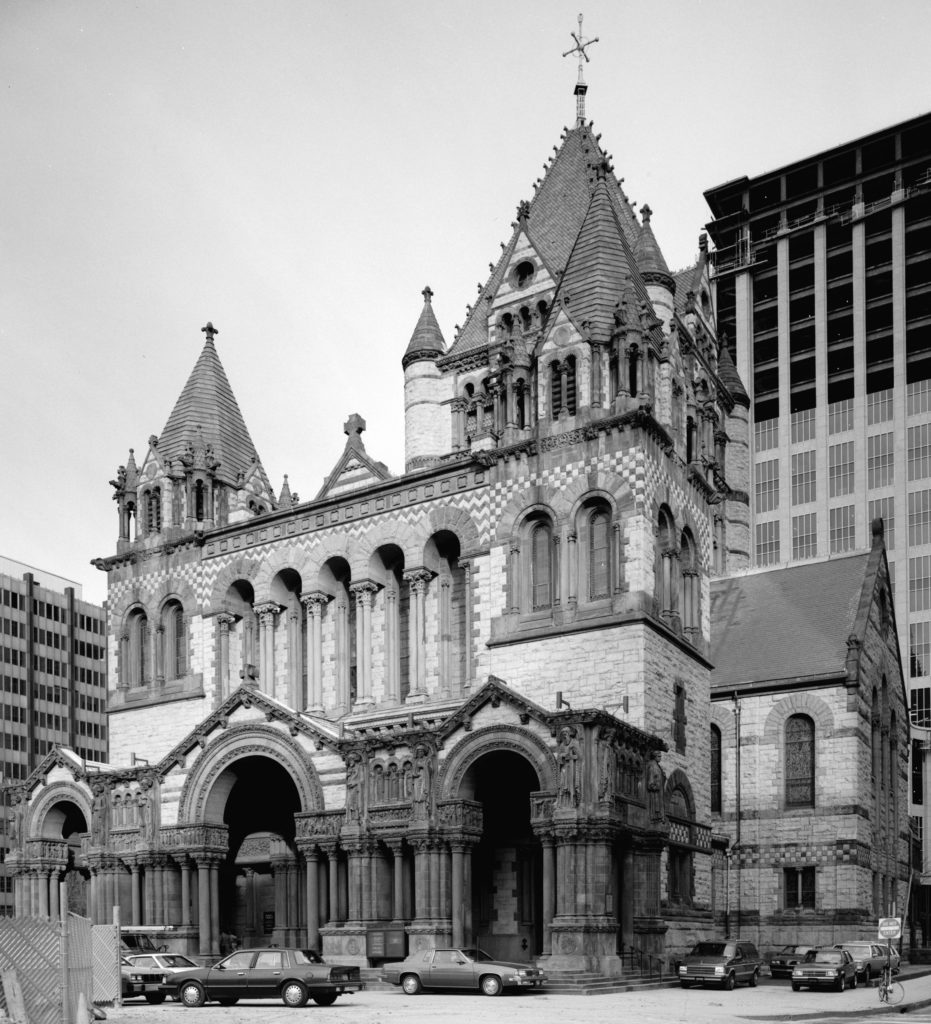

But Richardson increasingly found himself experimenting with the Norman features he saw in Europe, adapting them to his tastes and the ever-widening array of industrial materials now available. His efforts culminated with a breakthrough design for a major church in Boston. Completed in 1874 to great acclaim, Trinity Episcopal Church made H. H. Richardson something of a “starchitect,” and he moved to Boston where commissions awaited him.

Richardson’s breakthrough design, Trinity Episcopal Church in Boston. Courtesy HABS, Library of Congress

Universities were in particular need for architects at this time. College campuses were being laid out across the nation, and administrators sought an august and distinguished look for their edifices. Richardson’s brand of Romanesque seemed to nod appreciatively to higher education in England, which American universities tended to emulate, and its imposing presence abetted the prestigious ambience academies admired.

Harvard University commissioned Richardson to design a number of campus buildings, and because other institutions of higher learning often followed Harvard’s lead, Richardson’s brand of Romanesque came into demand on campus elsewhere. Other architects started replicating the look, and it spread.

Richardson himself designed scores of train stations, government and commercial buildings, courthouses, residences, lodges, monuments, and libraries across the country. According to biographer Jeffrey Karl Ochsner, Richardson and his firm designed for at least 150 projects, of which 85 were built.

In person, Richardson was the sort of man who filled a room and left everyone dazzled. His portrait artist Hubert von Herkomer described the nation’s most famous architect “as solid in his friendship as in his figure. Big-bodied, big-hearted, large-minded, full-brained, loving as he is pugnacious.” Some might say he was pure Louisiana.

But with so much success in the North, Richardson could hardly find time to return home to New Orleans or St. James Parish. It did not help that the lower South’s tenuous postwar economy offered few opportunities for architects of his stature. Recalled writer Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer, who knew Richardson personally, “he never even visited his native town again” after returning from France in 1865, “although I have heard him speak of a constant wish to do so.”

An untimely death of a kidney disease at age 47 denied Richardson that goal. Yet his work would nonetheless find a way home and leave an indelible mark.

His most direct contribution to his hometown came posthumously — and accidentally. While ailing, he had submitted designs for a library competition in East Saginaw, Michigan. But because of a difference of design philosophy with the client, the job went to another firm. Shortly thereafter, Richardson died, and the partnership of Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge assumed his commissions. The partners promptly reprised their mentor’s East Saginaw plans for a private book collection slated for a site near Lee Circle. Howard Memorial Library, built in 1888 and now the Taylor Library of the Ogden Museum, is the only Richardson design erected in New Orleans and the region.

Howard Memorial Library, seen here 1894 (interior), and 1900 (exterior), New Orleans’ only true H. H. Richardson-designed building. Photos courtesy Library of Congress.

But Richardson’s main contributions to New Orleans came indirectly, as the nationwide popularity of his style arrived back home to Louisiana, even if its creator did not. Colleagues influenced by his work began designing similar structures for local clients. A Romanesque annex, for example, was built adjacently to Howard Memorial Library in 1891; this would become Confederate Memorial Hall, Louisiana’s first museum. Mansions with the same colossal look arose along St. Charles Avenue for clients such as businessman and philanthropist Isadore Newman (completed 1892 at 3607 St. Charles; now gone) and cotton merchant and banker W. P. Brown (completed 1904 and now the largest house on the avenue, 4717 St. Charles). Other fine local examples of Romanesque include present-day 201 Camp, designed by Thomas Sully and completed in 1888; St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, designed by McDonald Berthas farther up Camp Street, completed in 1893 and demolished in 1958 for the Pontchartrain Expressway; and the Jewish Orphans and Widows Home (1887), now site of the Jewish Community Center on St. Charles and Jefferson.

Arguably the most prominent specimen began in 1892, when the city selected Dallas architect Max A. Orlopp Jr., who specialized in Richardson Romanesque courthouses, to unite Orleans Parish’s judicial, constabulary and punitive functions. Completed in 1893, the Criminal Courts Building and Parish Prison, according to one Picayune journalist, “reminds one of an old-time chateau or Norman country house, [with] circular towers rising in the center… castellated, with turrets, battlements and slits for the archers.” “A closer view,” he added, “shows…a mixing of the Romanesque [and] the Gothic.” Demolished in 1949, the courthouse occupied the site of today’s main branch of the New Orleans Public Library. (See my article on the Old Criminal Courthouse in the April 2016 edition of Preservation in Print.)

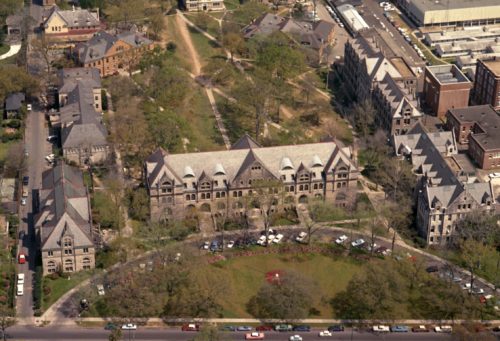

Perhaps H. H. Richardson’s premier indirect local contribution was to the university he once attended, by this time renamed Tulane. It administrators, including President William Preston Johnston, toured the Northeast to inspect peer institutions and had initially considered an Italian Renaissance design for their new uptown campus. Instead, Johnston held a competition in which he requested “plain brick, pressed brick and stone” construction and a “unity of design” for the campus.

Local architects dominated the submissions, and the winner was Harrod and Andry, whose emphatically Romanesque design for the Main Building (now Gibson Hall) and the Physics and Chemistry Buildings (now Hebert Hall and the Richardson Building) got under construction in January 1894.

My office is in the Richardson Building, and as I look out my window, I see a veritable campus-scape of Richardson Romanesque amid live oak trees and a grassy quad: seven monumental buildings dating from 1894 to 1942, all of gray rusticated stone or pressed brown brick, with broad arches and a heavy horizontality to them. Among the loveliest is Tilton Hall (1902), whose intricately carved façade features gargoyles and reptilian grotesques reminiscent of medieval buildings.

Tilton Hall, originally the library, brings to mind Henry Hobson Richardson’s penchant for libraries. Tilton Library later merged its book collection with that of its Romanesque counterpart on Lee Circle, Howard Memorial Library, and today they form the core collection of Tulane’s Howard-Tilton Memorial Library on Freret Street.

And whatever became of that project in East Saginaw, Michigan to which a dying Henry Hobson Richardson submitted his last design, only to be rejected? That building, Hoyt Library, opened in 1887 and remains in operation today. Its style: Richardson Romanesque.

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture is the author of “Bourbon Street: A History,” “Bienville’s Dilemma,” “Geographies of New Orleans” and other books. A version of this article originally appeared in Campanella’s Cityscapes column in the New Orleans Times-Picayune, July 8, 2016, and is presented here with permission. Campanella may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, or @nolacampanella on Twitter.