This story appeared in the September issue of the PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door monthly? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

When the Preservation Resource Center renovated the 20,000-square-foot former Leeds Foundry building into its headquarters in 2000, the project was done with energy efficiency in mind, but that was 19 years ago. Today, reducing the monthly utility bill has become a focus for the cost-conscious PRC. So this summer, we decided to join the NOLA Energy Challenge.

The city of New Orleans set a goal of cutting overall greenhouse gas emissions 50 percent by 2030. Current emissions in the city break down to 40 percent from industrial sources, 36 percent from residential and 24 percent from commercial, said Camille Pollan, program manager for the city’s Office of Resilience and Sustainability (ORS).

The NOLA Energy Challenge invites owners of commercial buildings to track their energy use for a year. By “benchmarking” energy use, participants can implement energy-saving strategies and see how that moves the needle. There are free trainings as well as information on how to receive incentives on energy-related improvements through Energy Smart, a division of Entergy. The trainings cover such topics as building automation systems, financing energy-efficiency efforts, tenant engagement, and “identifying and implementing operational/maintenance improvements.”

Advertisement

The PRC began benchmarking in July and set a goal of reducing the building’s consumption by 10 percent in a year. Small policies like turning off lights in bathrooms and other spaces when not in use, keeping the blinds down on the building’s large, south-facing front windows, and shutting down computers at the end of each day will help reduce energy consumption. According to EnergyStar.gov, “forgetting to shut down your computer just a handful of times will negate an entire year’s worth of incremental energy savings.”

Each floor in the PRC’s three-story building has its own thermostat. We have increased the office temperature to 75 degrees during the day and maintain 80 degrees during off hours via our programmable thermostats. Programmable thermostats are ideal because they regulate temperature and monitor energy use.

While it sounds easy to implement energy-saving measures on an individual level, getting an entire office of employees on board can be a challenge.

Tulane University’s downtown campus won the award for Greatest Tenant/Occupant Engagement Program in the 2018 NOLA Energy Challenge. Liz Hoekstra, former assistant director of Tulane’s Office of Sustainability, worked with Nicholas Pellegrini, a student studying environmental earth science and political science, to devise several strategies to get students, faculty and staff on board, including printing fliers with energy-efficiency tips tailored to different rooms or buildings; setting up information tables; and asking for occupants’ feedback. Five buildings on Tulane’s downtown campus participated, including Deming Pavilion, a residence hall at 204 S. Saratoga St.; Elks Place, home of the Tulane School of Social Work; the Environmental Science Building at 1700 Perdido St.; the Murphy Building at 131 S Robertson St.; and the Tidewater Building, home of the Tulane School of Public Health & Tropical Medicine at 1440 Canal St.

“Different people are motivated to save energy for different reasons,” Pellegrini said. “For the students, we emphasized the effect on climate change. For the labs, we spun it for cost savings. For the health building, there are a lot of health benefits of working in a sustainable environment.”

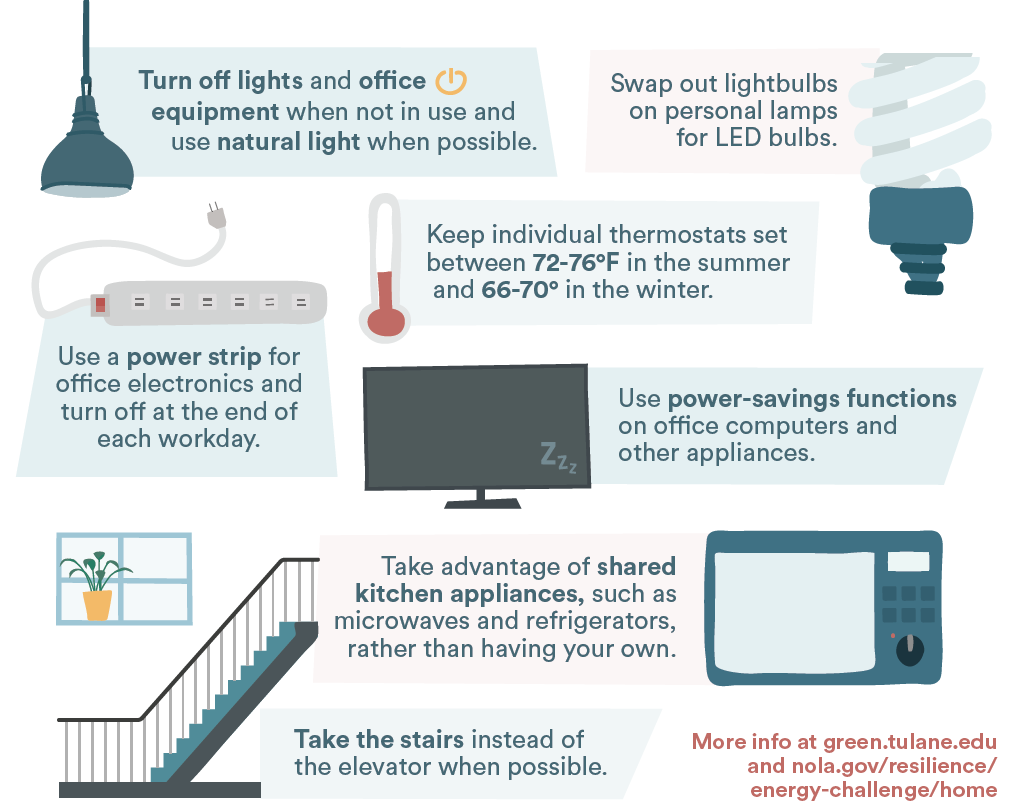

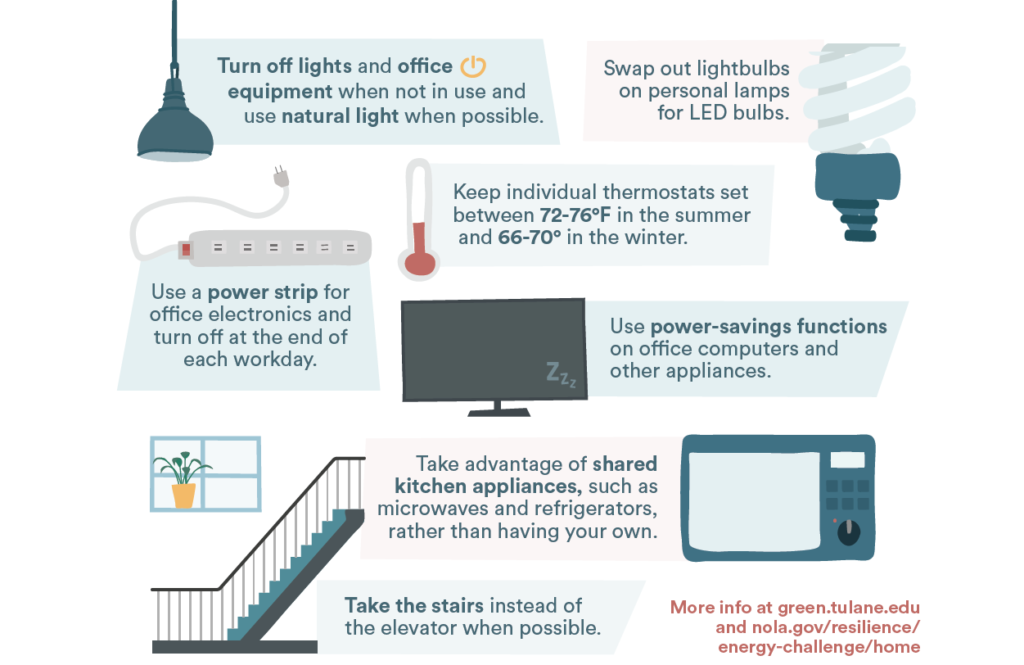

Energy-Saving Tips from Tulane’s Office of Sustainability

The fliers emphasized simple energy-saving tips, such as turning off lights and office equipment when not in use; using natural window light when possible; and taking advantage of shared kitchen appliances, such as microwave ovens and refrigerators, rather than having personal appliances in private offices. Pellegrini and Hoekstra also sent out surveys to students, faculty and staff with questions, such as, “Do you see something that’s not sustainable?” and “How can we help in your building?”

This year, Tulane expanded its efforts to include its Uptown campus in the NOLA Energy Challenge.

For businesses that partner with Entergy’s Energy Smart program, cost savings can be a big motivation. For example, Pel Hughes, a New Orleans marketing company housed in a 65,000-square-foot building, qualified for Energy Smart rebates when the company swapped out its old lightbulbs for LED. The upfront cost was $66,205 on a project that would save $16,692 every year. With the Energy Smart’s incentive — a return of $18,547 — Pel Hughes is projected to recoup the project cost in just under three years.

Entergy’s Energy Smart incentives have helped the city move toward its goal of emissions reductions, Entergy officials said. “In 2018, the combined goal between the East and West Banks of Orleans Parish was [to save] 46 million kilowatt hours, and Energy Smart achieved 109 percent of goal by saving over 50 million kilowatt hours,” said Derek Mills, manager of Entergy New Orleans’ demand-side management. “This results in the avoidance of an estimated 14,000 tons of carbon dioxide emissions.” The goal for 2019 is set at 53 million kilowatt hours.

This year, there are more than 50 commercial buildings signed up for the NOLA Energy Challenge, and it is a rolling admission process. Visit nola.gov/resilience/energy-challenge/home to register. In last year’s challenge, the F. Edward Hebert Federal Building earned the best Energy Star score overall. Other winners in the 2018 program included: Greatest Energy Reduction: US Custom House (General Service Administration); Greatest Energy Reduction Plan: 400 Poydras Tower (Hertz Investment Properties); Greatest Tenant/Occupant Engagement Program: Tulane University downtown campus; Overall Sustainability Champion/Leader: New Orleans Ernest N. Morial Convention Center.

Advertisement

Green upgrades in historic buildings

Historic preservationists often say, “the greenest building is the one already built.” That’s because existing buildings have “embodied energy” — the required energy and resources needed to manufacture the wood, metal, glass and other materials used in a building’s construction. By restoring a historic building — rather than demolishing it — that embodied energy is salvaged. By upgrading a building to more energy-efficient HVAC systems, reglazing original windows and sealing air leaks, a historic property can greatly improve its environmental footprint.

A good example is the Shrewsbury-Windle House, a historic landmark in Madison, Ind., a town where the summer climate can be similar to New Orleans. The circa-1949, 8,000-square-foot Greek Revival-style manse suffered from decades of deferred maintenance until it was bequeathed in 2011 to Historic Madison Inc., a local nonprofit. The organization raised money to completely restore the building and engaged the Engineering Collaborative in Indianapolis for the four-year project.

The Shrewsbury-Windle House functions as a museum and event space. To improve its energy efficiency, historic light fixtures were retrofitted with LED bulbs. Also, a Variable Refrigerant Flow HVAC system was installed. The system supplies the precise amount of refrigerant necessary to cool a room under its current condition, allowing the system to run less frequently while maintaining a comfortable temperature. Those improvements have made a difference. In past years, the house’s utility bills ranged between $800 and $1,000. This summer, bills have averaged $685 with the thermostat set to 76 degrees.

But not all of the improvements to the Shrewsbury-Windle house have required high-tech solutions. Historic Madison Inc. President and Executive Director John Staicer decided not to use high-efficiency glass (low-e) to reduce heat gain and UV damage to the interior because it would create an undesirable microenvironment within the windows. Instead, Historic Madison opted for light-blocking curtains, which are historically accurate and accomplish the same ends.

In Louisiana, a great resource for information on energy efficiency is the LSU AgCenter’s LA House program on the LSU campus in Baton Rouge. Many of its publications are online at lsuagcenter.com/lahouse.

Leah Solomon is PRC’s Event Coordinator.

Advertisements