This story appeared in the May issue of the PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

We can learn a lot about quarantine and isolation from the thousands of patients who passed through the gates of Carville, Louisiana’s national leprosarium. The name Carville refers to U.S. Public Health Hospital No. 66, later known as the Gillis W. Long Hansen’s Disease Center (“Carville”). From 1894 to 2005, Carville was the only national leprosarium in the continental United States. Its medical, cultural and architectural legacy lives on as the National Hansen’s Disease Museum and as the National Hansen’s Disease Clinical Center in Baton Rouge.

Hansen’s Disease, or leprosy, was once a life sentence of forced isolation. Thankfully, it is now curable, due in part to the treatments developed at Carville throughout the 20th century. Throughout history, leprosy was thought to be a curse from God or a genetic malady. Then, in 1873, Norwegian physician Gerhard Armauer Hansen, discovered the mycobacterium leprae. He realized that since the disease was bacterial, it could be communicable. It would take decades for physicians to realize that roughly 95 percent of the population is naturally immune to the bacteria, per the Centers for Disease Control. Hansen’s discovery reinvigorated the stigma surrounding the disease and led New Orleanians to demand leprosy patients be moved outside of the city limits. It was this outcry that led to the establishment of Carville.

In 1894, seven New Orleanians with Hansen’s Disease were forced onto a barge at gunpoint in the middle of the night. They began the journey upriver to Iberville Parish, landing on the Mississippi Riverbank at the site of an abandoned plantation home, Indian Camp plantation. The plantation, also identified on maps as Woodlawn Plantation in the antebellum period, is a two-story Italianate plantation home designed by famed architect Henry Howard and is the last plantation he designed before the Civil War.

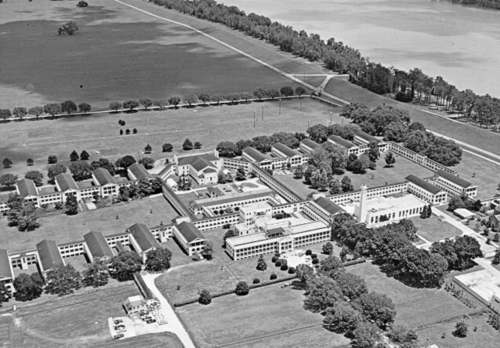

1: The dormitories of the Gillis W. Long Hansen’s Disease Center at Carville, La. Photo courtesy of the Louisiana Division of Historic Preservation.

2: In 1894, the leprosarium opened in the former Indian Camp Plantation, also identified on maps as Woodlawn Plantation in the antebellum period. The house is a two-story Italianate plantation home designed by famed architect Henry Howard and is the last plantation he designed before the Civil War. Photo courtesy of the Louisiana Division of Historic Preservation.

Indian Camp fell into disrepair following the Civil War. The owner, Robert Camp, had relied on slave labor to yield a sufficient crop, and without such labor force, he went into extreme debt attempting to pay for the home and its fineries. Furniture and architectural elements were sold off piece-meal, including a set of green and black Roman marble mantelpieces. In 1874, the house was seized by the bank and leased out annually as a tenant farm. The site would continue to yield a modest rice crop until 1891, when it was left derelict. By 1894, in the hopes of earning some income from the property, the bank rented the plantation to the state of Louisiana for use as a colony for Hansen’s Disease patients.

For the early part of the 19th century, the original home was flanked by a series of cabins for the 15 enslaved people tied to the estate. The original cabins would remain on site for the following century and serve as the first homes for the Hansen’s Disease patients. By 1896, four Daughters of Charity nuns arrived at Indian Camp to help care for the patients. The nuns were members of the same Catholic order that would provide aid to Charity Hospital in New Orleans. The nuns first went to work restoring the plantation home. After the site was purchased by the state in 1906, the nuns took on an extensive building plan which would allow them to better care for an increasing number of patients.

Their development of the hospital in the first decades of the 20th century would establish an architectural legacy that survives today. They relied on the needs of patients to determine how the site should grow and, in doing so, created a hospital complex fully accessible for patients with a myriad of mobility struggles.

Advertisement

Many Carville residents developed neuropathy, or nerve damage, as a side effect of Hansen’s Disease. Neuropathy leads to the loss of sensation, especially in extremities. Without sensitivity, it becomes much easier for patients to accidentally injure themselves. With this disease, muscles can also weaken and atrophy, causing a shortening of fingers and toes, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

These effects led to patients utilizing wheelchairs, bicycles and tricycles to move around the hospital. Between 1906 and 1916, new and existing buildings were connected by flat, wide covered walkways that patients could easily roll or ride across.

By 1917, the U.S. government had taken notice of Carville and passed legislation to officially designate it as a national leprosarium. After the First World War, the federal government officially bought Carville. Between the First and Second World Wars, Carville expanded and built a new laboratory and infirmary. Patients had the opportunity to build their own cottages in what would be known as “cottage city.”

In 1931, an enterprising patient, Stanley Stein, worked to reduce the stigma surrounding Hansen’s Disease by editing and publishing The Star, a newspaper written by patients and mailed to readers across the world. The name Stanley Stein is a pseudonym. Stein, like many patients at Carville, took a new name when he entered the hospital so he would not be associated with his family or previous life. The goal of The Star was to give readers a look behind the gates of Carville and to radiate “the light of truth on Hansen’s Disease.” Readers included actress Tallulah Bankhead, who became a friend of Stein’s and sent him a bust of her head that still resides in the museum.

Stein was not the only patient to have a job or develop a business at the hospital. Patient-owned businesses included a hair salon, photography studio, orchid cultivation, carpentry shop, laundromat, and two restaurants — one serving sandwiches and the other serving Chinese food. Patients could also work for the hospital, canteen or on-site school.

Advertisement

As patients began traveling to Carville from around the world, it became a cultural melting pot for the Louisiana traditions and intangible heritage the residents brought with them. Major yearly cultural events included a Mardi Gras ball and parade, during which patients built floats, passed out doubloons with armadillos on them (the unofficial mascot of Hansen’s Disease as they can contract the bacteria), and crowned a king and queen. Chinese New Year celebrations also were held. On display in the museum is a red and gold dragon float used during these events.

While the Second World War raged on, the war on Hansen’s Disease continued at Carville. Roughly 450 dormitory rooms were constructed during this period in a series of interwoven two-story buildings. The dormitories are tripartite with simple Classical Revival detailing and stucco finishes. Recessed ambulatories connect the structures. The simple Classical details are compatible with the Indian Camp plantation home design but do not overpower it. Other buildings constructed during this time include additional medical facilities and a new canteen containing a ballroom and a theater. The increased facilities also produced specialized orthotic shoes and artificial limbs.

1: The National Hansen’s Disease Museum features this example of a patient room. Photo by Ashley Gaudlip.

2: Stanley Stein’s desk is on display in the museum. Stein, a patient, reduced the stigma surrounding Hansen’s Disease by editing and publishing The Star, a newspaper written by patients and mailed to readers across the world. The name Stanley Stein is a pseudonym. Like many of the patients at Carville, Stein took a new name when he entered the hospital so he would not be associated with his family or previous life. Photo by Ashley Gaudlip.

Along with the extensive building plan, Carville was home to a “miracle.” Dr. Guy Henry Faget, the hospital director, pioneered the use of sulfone drugs to treat patients with Hansen’s Disease. This development was detailed in patient Betty Martin’s book, Miracle at Carville. The use of these drugs halted the progression of the disease. After continually negative skin tests, patients would then be allowed to leave Carville. Some would eventually come back if their Hansen’s Disease resurfaced, but this treatment completely changed the trajectory of the lives of Hansen’s Disease patients.

Throughout the latter portion of the 20th century, Carville continued to care for patients, though it would see fewer and fewer admitted. However, many patients who had spent their lives there opted to stay. Furthermore, former patients would choose to spend their retirement years on-site. From the late 1980s through the early 1990s, Carville also was used by the Bureau of Prisons to house non-violent offenders. They lived alongside Hansen’s Disease survivors for several years until the program was discontinued. By this point, patients were often elderly because new cases of Hansen’s Disease could be treated out-patient. These final days of Carville are detailed in Neil White’s memoir In the Sanctuary of Outcasts, which explores his time as an inmate.

The Carville Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1992. It was listed for its significance to both architecture and health/medicine, under Criteria A and C. The district features 26 contributing resources and 15 non-contributing resources, though the dormitories and some of the other buildings connected by ambulatories are counted as singular resources. The full National Register listing for the district is accessible in Louisiana’s National Register database and the United States National Archives.

Today, you can visit the National Hansen’s Disease Museum in Carville and walk through more than 4,000 square feet of exhibition space. Artifacts include Mardi Gras parade floats, medical equipment and an extensive collection of first-hand accounts of life at the site. After walking through the museum, you can continue to explore the buildings of Carville through a guided driving tour, which includes a narration from the museum curator, Elizabeth Schexnyder. The tour concludes at the cemetery, where former patients continue to be peacefully buried among the pecan trees. Dates on tombstones are as recent as 2018. The history of Carville deserves to be revisited, and it serves as a reminder of the unique historical role Louisiana played in the treatment of patients with this disease and the unique role architecture plays in adaptive function for its tenants needs.

Ashley Gaudlip is a Tax Incentives Reviewer with the Louisiana State Historic Preservation Office.

Advertisements