This story first appeared in the September issue of the PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door each month? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

It occupies one of the busiest corners at the nucleus of New Orleans’ oldest neighborhood. It anchors the single most Spanish Colonial street in the city, and faces one of the region’s most historic buildings. It’s the complex known today as Le Petit Théâtre and Dickie Brennan’s Tableau, at 616 St. Peter St., corner of Chartres, across from the Cabildo.

While the theater and restaurant buildings are 20th-century reconstructions, they pay homage to the circa-1790s Orue-Pontalba House and tell an interesting preservationist story.

The Orue-Pontalba House, based on the property’s chain of title documented in the Vieux Carré Survey, was at least the fourth structure to occupy these corner lots. The earlier buildings had many illustrious inhabitants, including Carlos Trudeau, surveyor and engineer for the Spanish government.

In 1788, the Good Friday Fire would destroy many structures in the area, including the building at this location. A year later, work began on a replacement, which itself was damaged in another fire on Dec. 8, 1794. Over the course of that period, a series of transactions transferred ownership of the property from Joseph de Orue to Andres Almonester y Roxas to Joseph Xavier de Pontalba.

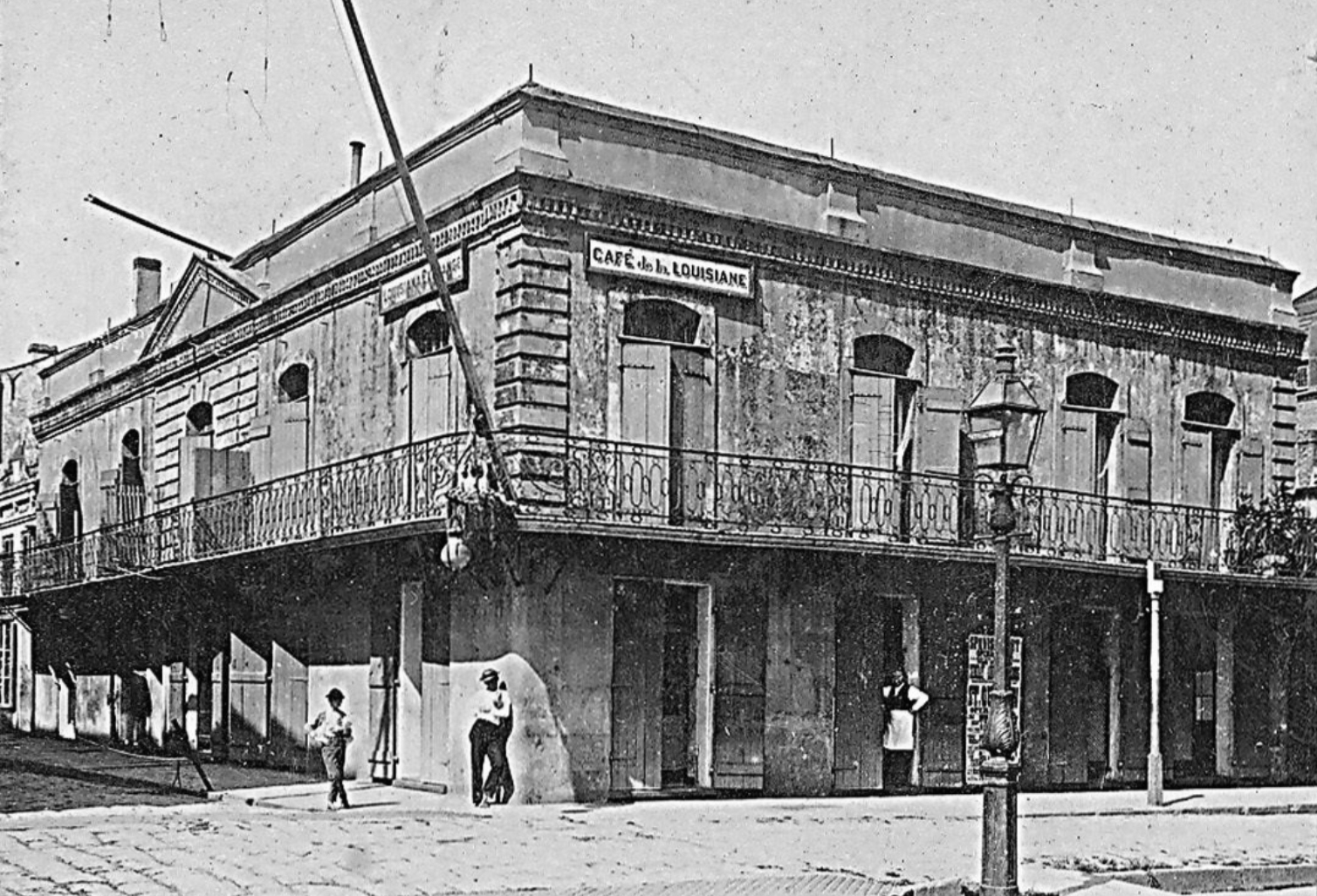

George Francois Mugnier photographed the Orue-Pontalba House in the 1880s. Image courtesy of the Louisiana State Museum.

In February 1796, Pontalba signed a contract with Hilario Boutte “to finish building a house at the corner of the Plaza.” As to who originally designed and built the edifice, indications point to French architect Gilberto Guillemard, who in subsequent years would create the Cabildo. The Orue-Pontalba House embodied the same sturdy, austere Spanish Colonial architecture as its neighbor, with thick masonry walls, a flat roof with tile terrace, an interior courtyard, stucco-covered walls with quoins and pilasters, a wrap-around balcony with cast-iron railings, and, like the Cabildo, a triangular pediment above the main entrance on Chartres Street. The result was a building that would have been very much at home in Havana or Mérida.

Despite its prominent appearance and location, the Orue-Pontalba House had a mix of occupants and uses, some of them rather ordinary. At times a saloon or eatery operated on the ground floor, while the upper floors had residential apartments, either for transient lodging or long-term leaseholders. Among the tenants were possibly the bishop of the cathedral and officials of the Cabildo (City Hall), according to records unearthed by the late architectural historian Samuel Wilson Jr. (1911-1993).

In the early 1900s, buildings on the adjacent lot on St. Peter Street were demolished, which opened up an opportunity for a group of uptown-based theatrical performers, first organized in 1916, to build a playhouse. Named the Little Theater, the organization purchased the open lot as well as the Orue-Pontalba House and commissioned architect Richard Koch of the firm Armstrong and Koch to design Le Petit Théâtre du Vieux Carre. Perhaps the most influential local architectural historian of the time, Koch (1889-1971) would single-handedly photograph and document scores of old buildings while also articulating the tout ensemble vision of an integral, protected French Quarter. Passionate as he was about historicism, Koch was more pragmatist than purist, feeling, in the words of researcher Abbye Alexander Gorin, that “old buildings, in order to survive, needed to be adapted for reuse [and] modern needs,” and that only a select few ought to “be preserved as they were originally built…in museum status.”

Advertisement

That philosophy made Koch, himself a theater member, the right man for this job. According to Koch’s protégé and colleague Samuel Wilson, Koch’s design for Le Petit Théâtre was the first new French Quarter building designed “in the character of the older structures in the area….a reflection of the 18th century Orue-Pontalba House at the corner, [also] owned by the theater and attached to the new building by a one-story foyer,” according to a 1980 interview of Wilson by Gorin.

Wilson added that “although traditional in character, [Koch’s] building is not in any way a copy of any older structure but an adaptation of traditional forms to meet the requirement of a new structure in a historic setting.” A few years later, wrote Gorin, “Koch connected the old and new buildings by a loggia and also designed a patio,” and in 1956, “Wilson increased the seating capacity of the theater by extending the upper balcony.” In this manner, Le Petit Théâtre set a historical precedent for what the late Malcolm Heard would later describe as “Vieux Carré Revival,” reflecting the sentiment “that new construction should be essentially scenographic and that it should fill in gaps…as inconspicuously as possible, leaving the limelight for older buildings.”

Unfortunately, costly maintenance for the aging landmark got deferred, and the Orue-Pontalba House gradually fell into serious structural disrepair.

What ensued was a dispute among strange bedfellows. On the one side was theater director Monroe Lipmann and his colleagues, who had long sought a different configuration of rooms for the expansion of their operation, while also balking at the cost and complexity of the renovation of the Orue-Pontalba House. Lipmann threatened to relocate the theater out of the French Quarter if the Vieux Carre Commission would not grant a demolition permit, something that, at the time, was unprecedented for truly significant historic structures.

Surprisingly, some leading preservationists supported deconstruction and reconstruction, albeit reluctantly, in part for the building’s advanced deterioration but also because they wanted the French Quarter to remain a living cultural space. They worried that Le Petit’s departure would diminish the neighborhood’s civic vibrancy.

Still skeptical, the Vieux Carre Commission pressed for a written commitment stating that reconstruction would indeed be forthcoming, and finally drew up the demolition permit. As the 173-year-old building was dissembled in 1962, “all but a thousand of the old Louisiana red bricks,” wrote Gorin, “turned to powder.”

This building, a 1963 reconstruction, anchors the single most integral Spanish Colonial streetscape in New Orleans, 600 Chartres. Photo by Randy Schmidt courtesy of Tableau restaurant.

Koch and Wilson, who by this time were professionally partnered, won the commission to rebuild the Orue-Pontalba House. They aimed to blend its façade into the Spanish Colonial aesthetics of its surrounding streetscape while accommodating the needs of the theater. Since the original plans were never found, Koch and Wilson drew conjectural inspiration from comparable buildings of that era. But when the client called for a façade-altering side space on the upper Chartres flank, Wilson resisted and withdrew from the project. The final reconstruction, completed in 1963, is thus attributed to Koch.

Many people today — including architects, preservationists, architectural historians and theater aficionados — tend to agree that the demolition of the Orue-Pontalba House was an unfortunate necessity, and its reconstruction generally successful, particularly since it succeeded in keeping Le Petit Théâtre in the Vieux Carre. Financial struggles in the early 2010s led to another controversial change — of incorporating Dickie Brennan’s Tableau restaurant into the theater’s space — and it is a credit to Koch’s work, as well as the renovation by Broodmoor LLC, that the designs accommodated the two very different programs quite well.

Best of all, the Spanish Colonial aesthetics of the building’s exterior, and the patina of age it has since developed, allows all three structures at the corner of Chartres and St. Peter — the 1962 reconstruction of the 1789 Orue-Pontalba house, the 1925 foyer and the 1922 Le Petit Théâtre — to help complete the single most Spanish Colonial streetscape in the city and region. By my count, the lake-side block of 600 Chartres is home to five of the French Quarter’s 39 surviving buildings from the Spanish dominion, six when we include the Cabildo across the street.

Richard Campanella is a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture and the author of “Cityscapes of New Orleans,” “Bourbon Street: A History,” “Bienville’s Dilemma” and other books. He may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, or @nolacampanella on Twitter.

Advertisement