This story appeared in the October issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

There would be no New Orleans were it not for the Bayou Road connection to Bayou St. John and Lake Pontchartrain. Like indigenous inhabitants before them, French colonials found these and other ridges and rivulets to be convenient backswamp accesses into lower Louisiana, offering an alternative to the Mississippi River when currents were too strong or shoals too numerous.

During such times, travelers from points east, namely Mobile and Biloxi would sail through the Mississippi Sound and into Lake Borgne, through the Rigolets or Chef Menteur Pass into Lake Pontchartrain and up Bayou St. John. They disembarked at what is now Moss Street near Grand Route St. John, De Soto and Bell streets, and continued on foot along a two-mile ridge through the swamps — today’s Esplanade Ridge, specifically Bayou Road and Gov. Nicholls Street — to reach the banks of the Mississippi, without going up the Mississippi.

So critical was this portage, it is inferred in the Company of the West’s ledger entry calling for the establishment of New Orleans, written in Paris in September 1717: “Resolved to establish, thirty leagues up the river, a burg which should be called Nouvelle Orléans, where landing would be possible from either the river or Lake Pontchartrain” (emphasis added).

The Chemin du Bayou became a lifeline for early New Orleans, as a reliable ingress and egress for human passage, a supply pathway for natural resources, and a fertile strip of land sufficiently close to the city to be used for food production. As early as 1708, some colonists from Mobile settled in the vicinity of the Bayou St. John/Bayou Road juncture and attempted to grow wheat there. While the project failed, the very fact that they had selected that spot to launch a new toehold in French Louisiana, 10 years before the founding of New Orleans, speaks to its geographical value.

Maps of the era consistently portray the curving portage to twisting Bayou St. John with cartographic prominence. Some parts of Bayou Road were more populated than the rear streets of the city itself, and building materials hauled along the chemin played a key role in early construction.

We still have at least two complete structures in the French Quarter that exhibit this historic bayou/city connection, and another on Bayou Road that is the last best vestige of this long-gone landscape.

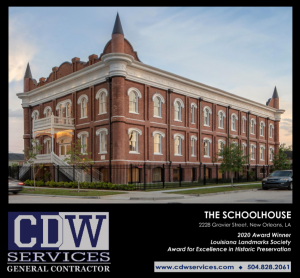

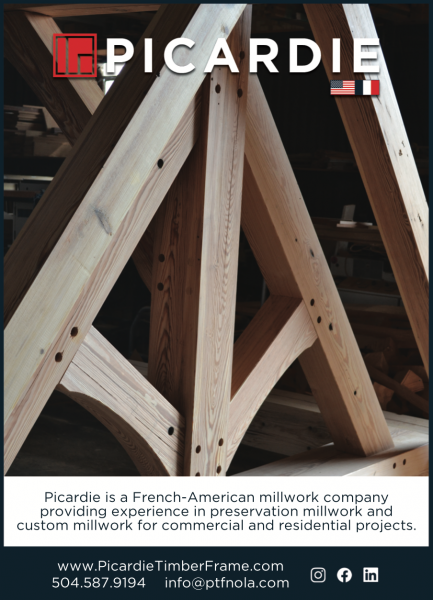

Advertisement

Corner of Burgundy and Dumaine Streets. Photo by Davis Allen.

Corner of Burgundy and Dumaine Streets. Photo by Davis Allen.

A walk down Burgundy Street presents block after block of antebellum cottages and townhouses interspersed by late-Victorian frame houses and shotgun doubles. At the corner of Dumaine Street, however, is a different visage: a much earlier-looking corner cottage, with a double-pitched hipped roof, two center chimneys and columbage walls — that is, hand-hewn cross timbers with aged “river bricks” set between the posts — traits all redolent of 18th-century Creole architecture. Picture a lower-slung and broader version of the more-famous Lafitte’s Blacksmith Shop, built in the same era on the corner of Bourbon and St. Philip streets, and that’s what stands on the corner of Burgundy and Dumaine.

This house was originally built on a Bayou Road parcel which had been purchased in 1777 by Gabriel Peyroux de la Roche Molive, a native of Mortain, France, who became a grain supplier to both French and Spanish colonial New Orleans.

Peyroux had married into a local French Creole family, the patriarch of which, François Caüe, had in 1754 purchased this corner lot on Burgundy, but left it vacant. In 1781, Peyroux decided to move his new Bayou Road house, first erected around what is now the North Dorgenois intersection, to his father-in-law’s city parcel on Burgundy and Dumaine. According to archival documents researched by Roulhac Toledano and the late Mary Louise Christovich, a man named Maurice Milon, whom Peyroux contracted “to take apart the house…situated on Bayou Road and to reassemble it in town” stipulated that “the house would be bousillier entre colombage…covered by wooden boards [and] lifted on blocks.”

While we don’t have any specific information on the move, it’s reasonable to surmise that Milon disassembled the Bayou Road house by removing the bousillage (mud mixed with Spanish moss) and extracting the pegs so that that the timbers could be carted into the city. As was common practice at the time, beams, joists and rafters were marked with Roman numerals to indicate which attached where.

Like so many other renovation projects, things went afoul between client and contractors. In 1782, Peyroux sued Milon for shoddy work, and a court ruled that Milon had to reimburse Peyroux. Afterwards, either Milon or another builder tried again, disassembling and re-erecting the timbers using the Roman numerals as guides, this time filling the frames with “river bricks” instead of bousillage. Incredibly, these markings, specifically V through XIII, are still plainly visibly along the alleyway into the St. Pierre Hotel, the current occupant of the 240-plus-year-old structure — a survivor of the fires of 1788 and 1794 as well as decades of urban densification and social transformation.

The Peyroux family owned the building up to 1850, at which time its title would go to Michel Albert Fabre and then eventually to a chain of subsequent owners, including Elie Charles E. Choisy; Julien Adolph Lacroix (a free man of color who acquired it in 1853); and others, according to the Vieux Carre Survey. Over that era, the building had been subdivided into three discrete households and used variously as apartments, storage and a corner store.

Probably since the 1780s, the outer walls of the Peyroux House have been covered with clapboards to protect the columbage from the elements. They were removed in the 1950s, perhaps to bring attention to the hotel that subsequently opened therein. While the intersection of Burgundy and Dumaine exudes a dense urban aura today, a hint of the corner cottage’s rural origins is still discernible in its low-slung massing and striking cross-timbered walls, giving it a visage the late architectural historian Samuel Wilson Jr. once described as nearly “medieval.”

Advertisement

913 Gov. Nicholls St. Photo by Davis Allen.

Which brings us to the Ossorno House, also in the rear of the Quarter, at 913 Gov. Nicholls St., the arterial extension of which was and remains Bayou Road. Like its brethren on Burgundy, this stately structure — a “pure Bayou St. John plantation house,” according to researcher Edith Ellicott Long, writing in 1966 — also initially pertained to Gabriel Peychoux when he lived along Bayou St. John.

Like the house on Burgundy, this structure also had a double-pitched hipped roof with center chimneys, although it differed in being raised well above the grade and fronted by a wooden gallery and outdoor staircase, all typical traits of Louisiana French Creole architecture, rather like Madame John’s Legacy (1788) on Dumaine Street. Sources indicate the house was built and/or dismantled around 1781, brought down the Bayou Road, and reassembled at the current site sometime between 1784 and 1787.

In response to the semi-rural nature of both the structural design and its new setting, the house was rebuilt in a manner set back from the street and given ample garden space all around, fitting for the time but highly unusual for the high-density French Quarter we know today.

In 1795, the house was acquired by Josquin Ossorno, a captain in the Spanish military, whose heirs would own it for generations to come. In the late 1830s, workers remodeled the Creole-style hipped roof, clearly depicted in an 1834 Notarial Archive document, into the gable roof we see today.

Since the Ossornos, only two other families have owned this building into the mid-20th century, after which it was converted into apartments (1960s), and recently renovated into condominiums. The Ossorno House remains the closest thing the modern-day French Quarter has to a genuine plantation house, and it speaks to the importance of Bayou St. John and Bayou Road in neighborhood formation.

Advertisement

2275 Bayou Road. Photo by Davis Allen.

To get an idea of what rural Bayou Road looked like circa 1800, a few decades before urbanization extended lakeward along the ridge and Esplanade Avenue was ploughed through to Bayou St. John, head to 2275 Bayou Road. There stands another French Creole-style house, almost West Indian in its ambiance, with its steep double-pitched roof, wooden gallery and spindle colonnades, all set back on a spacious lot.

Research by Toledano and Christovich indicates this may be the house of the Bayou Road habitation (farmstead) owned by Domingo Fleitas, built on a Spanish land grant made in 1801 and probably constructed shortly thereafter. Like the other two Bayou Road-affiliated houses still standing in the French Quarter, this one, too, appears to have been moved from its original location, probably when Esplanade Avenue was laid out in the 1830s. Now known as The House on Bayou Road and home to the Joan Mitchell Art Center, this early-1800s treasure gives us our last, best idea of what le Chemin du Bayou looked like two and three centuries ago, when it formed a rear gateway into New Orleans.

Richard Campanella is a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture and author of The West Bank of Greater New Orleans; Cityscapes of New Orleans; Bourbon Street: A History; and other books. Campanella may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, or @nolacampanella on Twitter.

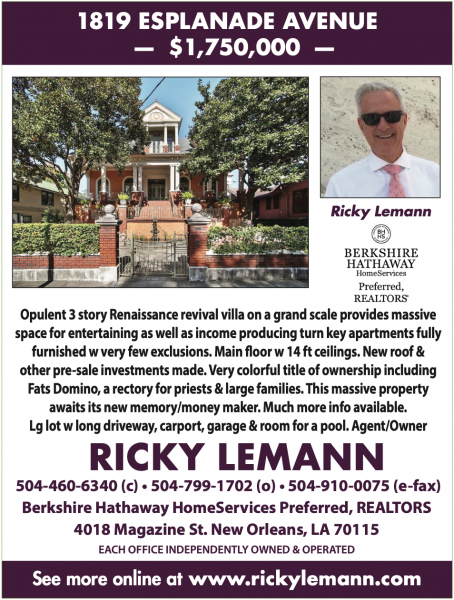

Advertisements