Header photo by Chris Granger

This story appeared in the June issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

Between 1816 and 1867, a network of 42 all-masonry forts were built to protect the United States’ most valuable ports, including New Orleans, Mobile Bay and Pensacola Bay. Called the Third System, these fortifications were the third phase of America’s early defense policy and were built to replace earlier forts constructed of less permanent materials.

The country’s primary military defense system at that time was the Navy, and coastal forts were built to aid sailing war ships in the protection of vital harbors and shipping channels. First and Second System forts were made of wood, earth and sometimes brick, but most went unfinished and were left to deteriorate. The Third System was the first permanent system of defensive fortification in the United States. They are distinguished from earlier systems by their exclusive use of brick and/or stone and a unifying architectural style rooted in classical and contemporary military theory of the day.

To protect the Gulf Coast, four main forts and three subsidiary structures were built in Louisiana; one fort was constructed on a Mississippi barrier island; two were built in Alabama; and three forts and one subsidiary redoubt were built on the gulf side of Florida. Of the 10 Gulf Coast forts completed in the Third System, all but two remain in relatively functional condition. Fort McRee in Pensacola Bay burned and was left in ruins during the Civil War, and now exists as just a few scattered and sand-covered foundation fragments. It is the only Third System fort in the country to be entirely lost.

Fort Livingston on Grand Terre Island is Louisiana’s only truly coastal fort, and it lies in flooded ruins after years of hurricanes and coastal erosion. Unlike Fort McRee, Fort Livingston is still identifiable as a masonry fort.

Third System forts, particularly those in the Gulf South, have complex and interesting histories. Half were designed by famed French military engineer Simon Bernard and built in part by enslaved African labor. The forts were built to protect America from a foreign invading force, but only ever saw combat during the Civil War.

Fort Pike and Fort Pickens, in Pensacola, were both used as prisons for Native Americans during the Seminole and Apache Wars, respectively. As recently as the 1940s, several of the forts were recommissioned to watch for German planes and U-boats in the Gulf of Mexico.

Third System forts are an invaluable link to America’s military and political history, but climate change and sea level rise could mean the loss of some, if not all, of them. The forts were strategically placed in one of three general locations on the gulf: islands, shoals and riverbanks/shorelines. The low and water-bound locations were due to the then common practice of skipping cannonballs along the surface of a body of water en route to a target.

Third System forts are typically found several miles from the cities they were built to protect. This can be confusing for modern visitors, but before the native forests were cleared and roads were built, coastal cities along the Gulf of Mexico were very much protected by nature.

Waterways were the only viable access points to cities like New Orleans and Mobile. Placing the forts a good distance from the cities they guarded allowed for more time to muster militia forces and transport munitions. It also meant that if the fort failed, invading forces still had miles of difficult landscape to navigate before reaching their target. In the time it took a foreign force to make its way through cypress forests and marshy bayous around New Orleans, a local militia could warn city residents and prepare for battle.

These sites were successful militarily, but they leave the forts extremely vulnerable to sea level rise. Each of the eight currently accessible forts will be negatively impacted by even a small increase in sea levels, but the four Louisiana forts are in particular peril. Forts in Mississippi, Alabama and Florida rest on the relatively firm footing of sandy peninsulas and barrier islands. They are susceptible to erosion and rising water, but their rates of land loss are lower than those observed in Louisiana. All but one of Louisiana’s forts are located in coastal wetlands, where the soil is much finer than sand. Decades of deforestation, canal dredging and off-shore oil extraction have destabilized Louisiana’s wetlands allowing saltwater to rush in and soil to wash out. Rates of relative sea level rise in coastal Louisiana are not only higher than those observed elsewhere on the Gulf, they are some of the highest in the world.

Third System forts across the Gulf Coast face preservation problems common to most masonry buildings of their age. They suffer from rising damp, salt accumulation and mortar loss. They are settling and cracking and always in need of some sort of repair, but hands-on preservation alone will not save these structures. Environmental protection and restoration of the forts’ surrounding areas are the most effective ways to preserve them.

The forts of Louisiana and the Gulf Coast are historically and architecturally fascinating, but they are also on the frontlines of climate change and act as prime examples of how protecting the environment helps preserve historic structures.

Advertisement

LOCATION: 27100 Chef Menteur Highway, New Orleans – map it!

OWNER: State of Louisiana

HISTORY: Fort Pike was the first Third System fort in the country. It served as a prison for Seminole Indians and African Americans captured during the Seminole Wars and later as a training ground for soldiers. African-American troops were among those trained at Fort Pike, including many who went on to become the famous Buffalo Soldiers of the 1870s. Fort Pike was operated as a state park from 1934 to 2015, when budget cuts forced its closure.

STATUS: Deteriorating and closed to the public.

Click images to expand

1: Fort Pike with view of the bridge in the back. File photo by Chris Granger. 2: Interior of the fort. File photo by Chris Granger. 3: Tourists explore the grounds in 1961. Photo by G.E. Arnold, courtesy of The Times-Picayune | New Orleans Advocate.

LOCATION: Chef Menteur Pass, New Orleans – map it!

OWNER: State of Louisiana

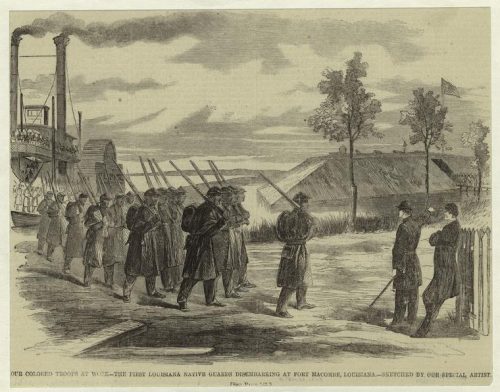

HISTORY: Fort Macomb is the twin of Fort Pike. It never saw combat and was used almost exclusively as a training post. Among the famous regiments and generals to serve there were the 20th Infantry Corps d’Afrique and President Zachary Taylor.

STATUS: Deteriorating and closed to the public.

Click images to expand

1: Ruins of Fort Macomb. Photo courtesy of Infrogmation of New Orleans. 2: Fort Macomb from above. Photo by NOLADG. 3: A Civil War scene at Fort Macomb. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Advertisement

LOCATION: 38039 LA 23, Buras – map it!

OWNER: Plaquemines Parish

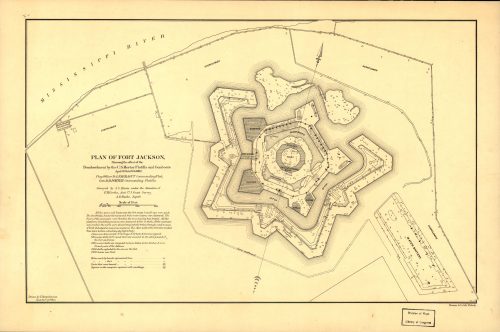

HISTORY: Fort Jackson saw the most combat of all of Louisiana’s Third System forts. It was a Confederate stronghold until a 10-day battle with Union troops led the soldiers to mutiny. Fort Jackson was eventually donated to Plaquemines Parish and operated as a park before being damaged by Hurricane Katrina.

STATUS: Damaged but stable. The fort is closed to the public.

Click images to expand

1: Fort Jackson bunker. Photo courtesy of Infrogmation of New Orleans. 2: Plan of Fort Jackson showing the effect of the bombardment by the U.S. mortar flotilla and gunboats. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress. 3: The FEMA Federal Preservation Unit assisting the state in retrieving and restoring historical objects from inside of Fort Jackson. Photo courtesy of the National Park Service.

LOCATION: Grande Terre Island – map it!

OWNER: State of Louisiana

HISTORY: Fort Livingston was the last Third System fort built in Louisiana. It never saw combat and was turned over to the state in 1923. Grande Terre Island became a state wildlife and fisheries protected area in 1955.

STATUS: Severely damaged and closed to the public.

Click images to expand

1: Ruins of Fort Livingston with oil containment booms in response to the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill disaster. Photo courtesy of the National Park Service. 2: Barrel-vaulted passageway between the courtyard and the moat on the northwest side of the fort. Photo courtesy of the National Park Service. 3: Aerial photo of ruins of Fort Livingston. Photo courtesy of the National Park Service.

LOCATION: Lake Borgne – map it!

OWNER: St. Bernard Parish

HISTORY: Fort Proctor is not officially a fort, but rather a subsidiary structure. Construction began late in the Third System and was halted by the Civil War. The plans for Fort Proctor were never realized, and it remains in its unfinished state.

STATUS: Damaged but stable.

Click images to expand

1: Exterior of Fort Proctor in 2020. Photo by Davis Allen. 2: View into the interior of Fort Proctor in 2013. Photo by Shannon Dosemagen.

In addition to building new forts, the Third System included reinforcements to existing structures. Battery Bienvenue in Lake Borgne and Fort St. Philip in Plaquemines Parish were both extant defenses updated and reinforced to function as part of the Third System.

A Louisiana native, Lindsey Walsworth has a master’s degree in historic preservation and environmental ethics and works as an architectural historian for HNTB Corporation in Atlanta, Ga.

Advertisements