This story appeared in the May issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

In the parade of proud structures lining St. Charles Avenue, Touro Synagogue stands out with a wealth of details great and small.

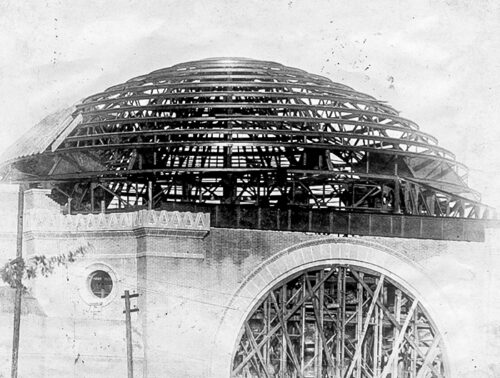

Most prominent is the massive 72-foot-wide dome, which rests atop a building of blond brick featuring bright terra-cotta details and undulating arches. Complementing this structure, which was dedicated in 1909, is a chapel erected eight decades later to accommodate the needs of a growing congregation. Its dominant feature from the sidewalk is a diamond-shaped stained-glass window honoring the newspaper executive Norman Newhouse. Designed by New Orleans artists Ida Kohlmeyer and Gene Koss, the design bears a kinship to the works of Marc Chagall. By night, it glows over the avenue.

With 634 member families, Touro Synagogue is dedicated to serving the spiritual needs of its congregation, but it also has housed programs serving the temporal needs of the community at large, including refugee-resettlement initiatives, a garden to grow produce for the Broadmoor Food Pantry, and rooms that have been incubators for four charter schools, said Teri Hunter, the temple’s former chair of social-justice initiatives.

“The walls between our congregation and the community are very porous,” said Hunter, who also is the congregation’s former president. “Judaism has been known as a religion of study and prayer, but it is also known for activism. … Touro has connected people and social justice under that great dome.”

Advertisement

But even buildings housing organizations with the most high-minded goals require down-to-earth maintenance. In Touro’s case, that includes replacing the flat roofs and the heating and air-conditioning systems, said Rabbi Katie Bauman, adding that the synagogue at 4238 St. Charles Ave. hadn’t undertaken such large-scale projects since the chapel was built in 1989.

Those two jobs provided the impetus for Touro Synagogue’s launch of a $4.5 million capital campaign, which, she said, also would include money to buy an elevator and generator.

To help pay for these undertakings, Touro applied in 2019 for a grant from the National Fund for Sacred Places, which Partners for Sacred Places operates with the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

In the summer of 2020, the synagogue was awarded $126,000 with the provision that Touro come up with twice that amount — $252,000. “The grant depends on raising the match, which we’ve already done,” Bauman said. “We’re thrilled to receive the grant.”

Work, which the pandemic has delayed, should start before the end of the year and finish in two years, said Kurt Jostes, the synagogue’s executive director.

Touro was only the second synagogue to receive such a grant, said Gianfranco Grande, Partners for Sacred Places’ executive vice president. The first was Congregation Beth Ahabah in Richmond, Va. Money for this program comes from the Lilly Endowment Inc. and the Gerry Charitable Trust.

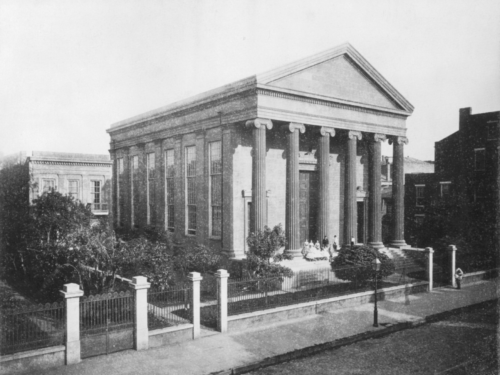

1: The synagogue initially occupied a building on Carondelet Street until it moved to St. Charles Avenue. Image courtesy of Touro Synagogue. 2: The 72-foot-wide dome that sits atop Touro Synagogue was constructed in 1908. Photo by John N. Teunisson, courtesy of the Louisiana State Museum.

The grants program was created in 2016 for Christian churches, Grande said, “but we make exceptions when a story is so great, as in the case with Touro. … I was impressed by their community engagement. I talked to my colleagues, and we allowed them to make the application. It’s a very important place. They do a very important job.”

Bauman called activity in the community “a very important part of our identity and our involvement here.”

Consequently, she said, being valued for such pursuits “feels like the most significant part of this honor. Yes, we have a magnificent building — it’s so remarkable — but there are a lot of magnificent buildings. What they really were recognizing is a combination of the building and the community outreach.

“There is, I think, a sense that religious institutions tend to keep to themselves, tend to stay inside and serve their own parishioners. Certainly, in very old congregations, that can be the predisposition, so this grant is honoring the fact that we are as vibrant as we are historic. We’re as committed to our community as we are to our architecture and to ourselves.”

Advertisement

Touro Synagogue is the descendant of Congregation Gates of Mercy, which, when it was established in New Orleans in 1828, was the first temple outside the 13 colonies. In 1881, it merged with Congregation Dispersed of Judah to become a temple that would be named for the New Orleans merchant and philanthropist Judah Touro.

The synagogue, which joined the Reform movement in 1891, occupied a building on Carondelet Street until it moved to St. Charles Avenue.

New Orleans architect Emile Weil won a competition to design the temple, which was built in 1908. According to the synagogue’s grant application, the building contains Byzantine and Moorish elements in a nod to the heritage of Sephardic Jews, who came from Spain and Portugal. With vast arched window bays mimicking the dome’s curve, the temple’s side and rear reflect the influence of the architect Louis Sullivan. Also evident are multicolored pieces of art glass.

Overall, the temple is an echo of the Wiener Werkstätte style, a clean, modernistic approach to design from the early 20th century that was to influence the Art Deco and Bauhaus movements. The synagogue’s plans and elevation were published in The American Architect magazine in October 1909.

The temple is an echo of the Wiener Werkstätte style, a clean, modernistic approach to design from the early 20th century that was to influence the Art Deco and Bauhaus movements. Image courtesy of Touro Synagogue.

In the sanctuary, worshippers have a clear view of the bima, the raised platform with a desk from which the Torah and Haftarah are read, and the ark, the chamber containing the Torah scrolls. The ark is made of cedar pillars from Lebanon.

Membership has grown by 13.2 percent since 2015, Bauman said. “A significant amount of growth … happened during the last two years as people began to feel the importance of being attached to a community with a purpose. We were able to harness that energy and continue to build.”

Although planning a capital campaign during the pandemic has been difficult because so much of the world has been on lockdown, with schedules upended, she said, “It felt to me like we were going to come out of the pandemic with everyone having a very firm grasp of why a religious community is important, and what the power of it is and what it can do that nobody else can do.”

Advertisements