At this time of year, foot traffic swells, porches become gathering spots, and music fills the streets of the historic neighborhoods surrounding the Fair Grounds Race Course, as an estimated 400,000 people pass through the gates of the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. As all eyes and ears turn to the festival grounds, it’s fun to explore the streets around it. One little street right near the festival’s gates has an interesting name and a hidden history.

Crossing over Esplanade Avenue, Maurepas Street and Ponce De Leon Street is Mystery Street in the Esplanade Ridge Historic District neighborhood. According to John Churchill Chase’s book Frenchmen Desire Good Children And Other Streets Of New Orleans, the history behind the street’s name is fittingly “something of a mystery.”

Let’s take a walk around and explore the mystery.

Mystery Street is only three blocks long. Today, you’ll see historic homes with modern SUVs and Teslas in driveways and parked on the street. On the right side of its 1300 block, you’ll find Alcée Fortier Park. Named after philanthropist and Esplanade Ridge resident Alcée Fortier, this space has been a public park since 1926. Situated at the junction of Mystery Street, Esplanade Avenue and Grand Route St. John streets, the park has stayed relatively the same since it opened nearly a century ago.

Mystery Street was mostly developed at the turn of the 20th century, with many of the existing buildings there today dating to the early 1900s through the 1930s.

What was it like to live on Mystery Street in the mid-20th century? While we don’t have a time machine, we do have U.S. Census records that can give us a snapshot of who lived in this vibrant neighborhood, what they did for a living, and whether they rented or owned their homes. The National Archives releases census records to the general public 72 years after the information was collected. Since many of the houses in this area were built prior to 1940, we picked the 1940 census records to give us a view back in time. These records were released to the public in 2012.

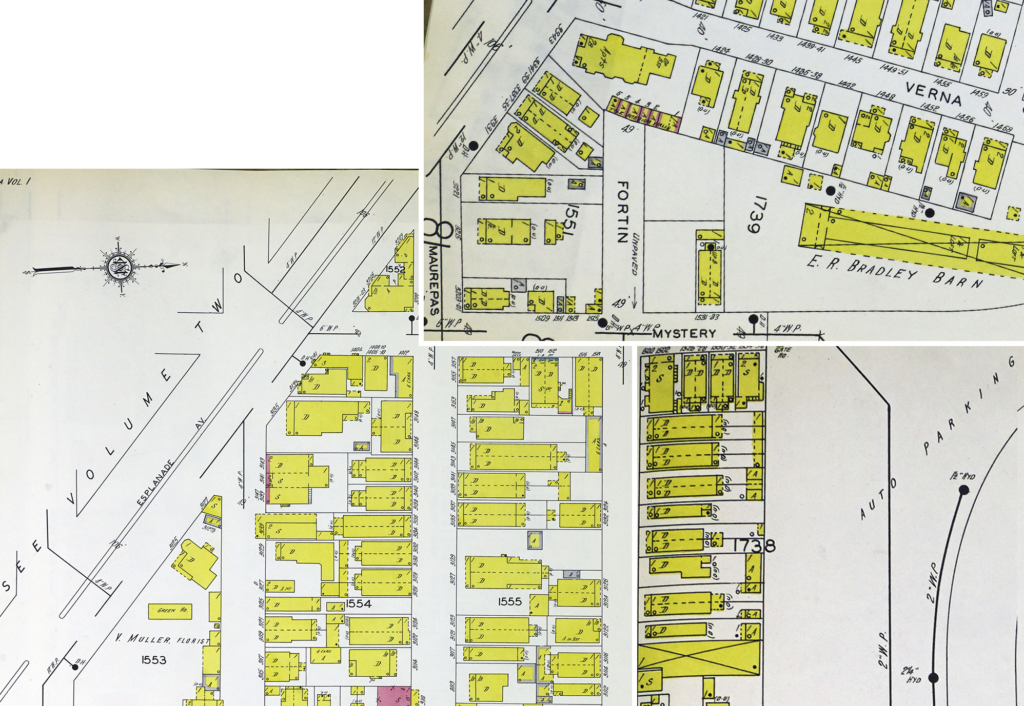

To help get an even clearer picture of what life was like on Mystery Street in 1940, we turned to Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, available through the public library. These maps were drawn in the 19th and 20th centuries and had detailed information about individual buildings.

A collage of multiple pages from the Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps provide a snapshot of the buildings on Mystery Street and the surrounding neighborhood in 1940. (Click to expand image)

In 1940, New Orleans was the largest southern city in the United States, with a population of half a million. After World War II, between 1940 and 1960, the city continued to swell, adding about 133,000 people.

Back in the 1940s, many different people called Mystery Street home, including painters, bookkeepers and waiters.

In 1940, on the corner of Ponce De Leon and Mystery streets, at the present-day Canseco’s Esplanade Market, lived the De Ben family at 3135 Esplanade Ave. Albert De Ben, a 66-year-old proprietor, and his wife, Elizabeth De Ben, 54, lived in their home with their three children. A couple, John and Jane Williams, rented the home’s second unit and worked as salespeople. (In 1981, Whole Foods Company opened a location at the site of the former De Ben home, and the property was bought by grocer Sinesio Canseco in 2007.)

Like many other Mystery Street properties at the time, the De Ben’s home was a smaller dwelling. In New Orleans, 52 percent of the city’s housing units were built by 1959, with almost half (22 percent) of them being built between 1940 and 1959, according to a City of New Orleans planning report. Most family homes built before World War II in New Orleans had a simpler, less suburban look. Homes with more suburban appeal would take off in popularity post-war. Pre-World War II homes were “low-rise single family, two family, and small multifamily (generally no more than five unit) structures,” according to a City of New Orleans planning report.

Neighbors to the De Bens, the Carambat family lived at 1406 Mystery St. Hazel Carambat, 45, a saleswoman, rented a home there and lived with her three children. Hazel’s son, Jack, 22, was a foreman, and her daughter, Janet, 18, was an office clerk. Their neighbor, Marie Dastargue, 67, was a widow renting the home at 1410 Mystery St. Marie lived with her son and two grandchildren. Marie’s son, Ferdinand Dastargue Sr., 44, was a bookkeeper.

Today, on the left side of Mystery Street’s 1400 block, you’ll see the Santa Fe restaurant. This building wasn’t always a restaurant. According to a 1950 New Orleans Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, the property at 3201 Esplanade Ave. was an auto garage with a store attached. One small building at this address turned into a fast-food restaurant by 1987. That same year, the fast-food place was torn down and made into a Whole Food Co. parking lot, according to a 2017 Times-Picayune article.

In 1940, near the corner of Mystery and Maurepas streets, on the right side of Mystery Street’s 1400 block, lived Lillian and Edward Kearney. Edward, 55, a ship foreman, and Lillian, 54, lived at 3148 Maurepas St. The Kearneys’ neighbors were siblings. At 3146 Maurepas St., Paula Edwards, 54, lived with her sister, Olga Kern, 55. Edwards was a file clerk renting the property. In fact, only four of 20 known residents around Mystery Street actually owned their homes in 1940. (Only about 44 percent of people owned homes in the United States that year.)

Across the street from the sisters lived the large Ferdinand family at 3157 Maurepas St. Louis D. Ferdinand, 47, a carpenter, and his wife Alice, 41, were renters and lived with their four children. Louis’ son, Louis Ferdinand Jr., 21, was a “carhop” or a waiter at a drive-up restaurant. His daughter, Marion Ferdinand, 20, was a saleswoman. Interestingly, the Ferdinand home was turned into a radio and television store, the Bandera Radio and TV Service, sometime before 1953. But that didn’t last long. By 1957, the property was transformed into a barber shop, according to an announcement in the New Orleans States newspaper.

Newspaper advertisements for businesses at 3157 Maurepas

The Times-Picayune, December 14, 1953

The Times-Picayune, December 15, 1953

The Times-Picayune, September 20, 1957

The Times-Picayune, October 22, 1957

The Ferdinands’ next-door neighbors were the Deans. At 3155 Maurepas St., junior clerk Harry Dean, 34, and his wife Mary, 36, lived with their two children, Donald and Dorothy. The Deans were also renting their home. Down the street from the Deans lived a young couple, the Buas. At 1510 Mystery St., Joseph Bua, 25, a hauler, lived with his wife Antoinette, 23. The Buas lived next door to another couple, the Fortunados. At 1512 Mystery St., distributor Benny Fortunado, 33, lived with his wife Esther, 28.

Further down from these two couples was the Vernaci family home. At 1516 Mystery St., Joseph P. Vernaci, a 33-year-old oiler, lived with his wife Sophie, 25, and their two young sons. The Vernacis’ next-door neighbor was 48-year-old seamstress Mae Purtee. She lived with a lodger and laborer, Louis Ryan, 59. At 1518 Mystery St., Mae was the head of her household. Out of the 20 nearby residents in the 1940 census, eight women and 12 men were listed as the head of their household. Of those eight women, four were married, and two were widowed as stated in census records.

Now, on the right side of Mystery Street’s 1500 block in the 1940s, there were buildings there that you no longer see today. In 1940, Sauleta Pilarinos, 19, lived alone with her five-month-old daughter, Lillian, at 1526 Mystery St. Sauleta’s neighbors were the Kenneys. At 1528 Mystery St., a bricklayer Edward Kenney, 49, lived with his wife Mary, 45. According to federal census records, this address existed in 1950, but the building has since been demolished. At 1534 Mystery St. lived a family of painters. There, painter John Harris, 54, lived with his wife Lillian, 37, and their son, John Williams, 18, who was also a painter.

Across the street, on the corner of Mystery Street and Maurepas Street, lived a waiter Julio Gonzalez, 32, and his wife Rose, 32, at 3201 Maurepas St. Next door to the Gonzalez family at 3203 Maurepas St. lived seamstress Angelina Andrade, 47, and her son Anthony Amato, 29, who was a salesman. Down at 1509 Mystery St. lived a beautician Dorothy M. Perry, 20, who was renting. Another address missing from today’s maps is 1533 Mystery St., where Joseph Manale, 48, a paymaster, and his wife Louise, 42, lived. The building at this address existed in 1950 and was later demolished.

At Mystery Street’s end, you come to Fortin St. Here, you can see the parking space for the Fair Grounds. In 1940, Italian immigrant and salesman Louis Pisciotta, 47, and his wife Lena Pisciotta, 43, lived with their son, Micheal, 14, at 3131 Fortin St. Down from the Pisciottas lived the Berinatos. Salvador Berinato, 49, a junior clerk, and his wife Adele Berinato, 35, lived at 3145 Fortin St. Salvador’s native language was Italian, and both of his parents were born in Italy. Despite the decline in immigration in 1940, New Orleans’ immigrant population was the highest it had ever been that year, according to an article by the University of Richmond.

By the 1950s, the end of Mystery Street where it meets Fortin Street was unpaved. Past Mystery Street’s end, you could see the E.R. Bradley Barn, which was part of the Fair Grounds. The barn belonged to Col. Edward Riley Bradley, who was an American racehorse breeder who owned and operated the Fair Grounds from 1926 to 1933. The New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival made its way to the Fair Grounds in 1972 and has stayed ever since.

A lot has changed in New Orleans since 1940, including population shifts and architectural trends. If you happen to walk down Mystery Street on your way to Jazz Fest, you might feel closer to these streets knowing who walked them over 80 years ago.

Hope Slocum is PRC’s Communications Intern

Sources:

• Insurance Maps of New Orleans, Louisiana Volume Two 1940. Sanborn Map Co., vol. 2, 1940.

• Insurance Maps of New Orleans, Louisiana Volume One 1937; Revised to October 1950. Sanborn Map Co., vol. 1, 1950.

• “1940 United States Federal Census.” Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012.

• “1950 United States Federal Census.” Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2022.

• “Times-Picayune, 14 Dec. 1953.” NewsBank: America’s News – Historical and Current, p. 46. Accessed 31 Mar. 2024.

• “Times-Picayune, 15 Dec. 1953.” NewsBank: America’s News – Historical and Current, p. 41. Accessed 31 Mar. 2024.

• “Times-Picayune, 6 Sept. 1981.” NewsBank: America’s News – Historical and Current, p. 56. Accessed 21 Apr. 2024.

• “New Orleans States, FINAL HOME ed., 22 Oct. 1957.” NewsBank: America’s News – Historical and Current, p. 23. Accessed 31 Mar. 2024.

• Chase, John C. Frenchmen Desire Good Children And Other Streets Of New Orleans. Touchstone, 1997.

• “FAQ.” New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival and Foundation, 2024, https://www.nojazzfest.com/faq/. Accessed 31 Mar. 2024.

• “Alcée Fortier Park.” The Cultural Landscape Foundation, link. Accessed 31 Mar. 2024.

• “Fair Grounds Hall of Fame Biographies & Marie G. Krantz Lifetime Achievement Award Winners.” Fair Grounds Racing Hall of Fame, link. Accessed 31 Mar. 2024.

• “A Brief History of the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival.” New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival and Foundation, 2024, link. Accessed 31 Mar. 2024.

• “Volume 3 Chapter 2 New Orleans Yesterday and Today: Population and Land Use Trends.” City of New Orleans, link. Accessed 1 Apr. 2024.

• “Immigration and Settlement Patterns, New Orleans, 1940.” University of Richmond, link. Accessed 1 Apr. 2024.

• Fetter, Daniel K. “The Twentieth-Century Increase in U.S. Home Ownership: Facts and Hypotheses.” National Bureau of Economic Research, link.

• Pontchartrain, Blake. “Blake Pontchartrain: Off to the races with a brief history of New Orleans’ Fair Grounds.” Gambit, link.

• Daffin, Melinda. “Long-gone grocery stores of New Orleans: Vintage photos from The Times-Picayune.” The Times-Picayune, link.

• “Times-Picayune, 20 Sept. 1957.” NewsBank: America’s News – Historical and Current, p. 13. Accessed 25 Apr. 2024.