Within these Walls

Biographical portraits of New Orleans residents and their homes

This story appeared in the February/March issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

This article was updated on March 6 to further acknowledge the slaveholding past of the Villere, de la Vergne and Armant families.

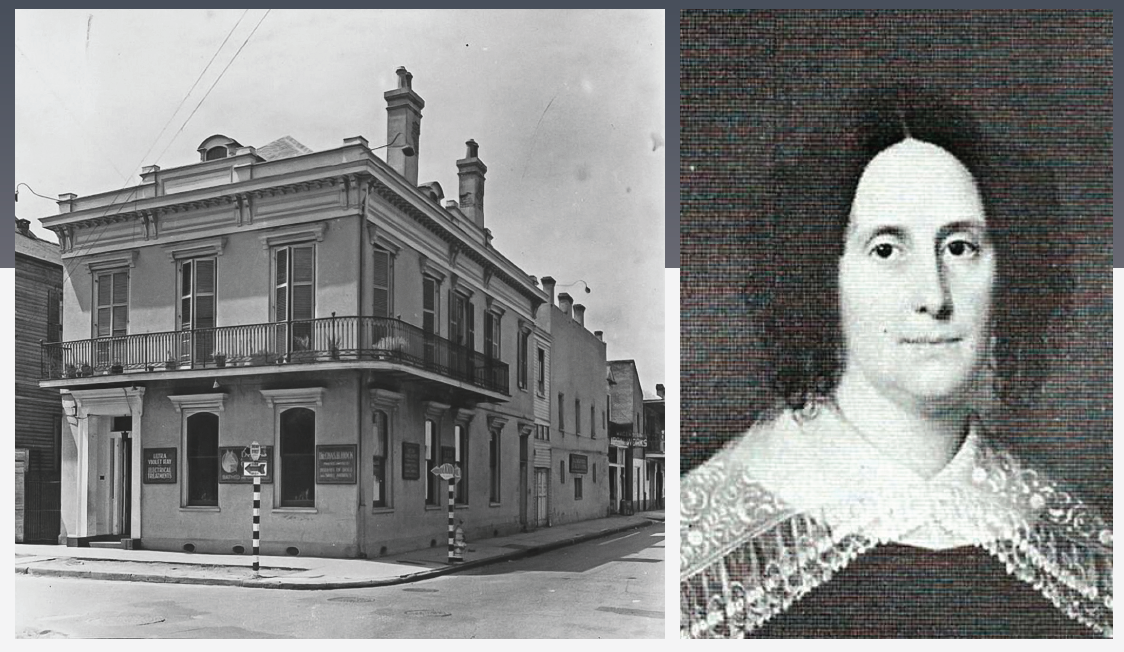

On April 27, 1850, Marie Adele Villere set out to purchase a home for herself and her family. Joseph Basque sold her an 1831 brick townhouse built in the federal style on the corner of Esplanade Avenue at Burgundy Street. Her deceased husband, Hugues de la Vergne, had been a major on the staff of General Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans. He also served as secretary of state and was a colonel on the staff of one of the early governors of Louisiana.

In addition to being the wife of an elite Creole gentlemen, Madame de la Vergne had her own prestige, power and fortune. She was the daughter of Jacques Villere, the second governor of Louisiana, who also happened to be the first Creole head of the state. Along with her inheritance from her father and her dotal rights, she gained half of her husband’s property upon his death in 1843, leaving her with cash, real estate and property in enslaved individuals.

The house on Esplanade Avenue would become the center of the de la Vergne family and the place where the matriarch could live out the remainder of her life in comfort, surrounded by her loved ones. Residing with her was her son Jules, an attorney and member of the state legislature; her daughter and son-in-law Cesaire Olivier; and another daughter named Adele. Adele and her husband, Terence Armant, son of a wealthy sugar planter and illustrious Creole family, had been married for five years and had three small children.

Advertisement

On the night of April 19, 1847, the harmony of the de la Vergne home was shaken by abuse and violence that would forever alter the life of Madame de la Vergne’s daughter and namesake. The entire family was downstairs at breakfast the next morning when 22-year-old Adele Armant took her usual seat at the table and burst into tears. She asked for the protection of her family and revealed that her husband had constantly beaten and ill-treated her. The previous evening Terence Armant informed her that each time he slapped the enslaved domestic servant he would also slap her. Armant appeared behind his wife and declared that he had not applied all his physical force against her, as if excusing his behavior. The de la Vergne family immediately asked him to withdraw from the Esplanade home and summoned two of his brothers to persuade him to leave immediately.

One month later, Adele de la Vergne Armant, with the support of her family, petitioned the court for a divorce from her husband, accusing him of cruel treatment and outrages toward her so grievous that it was insupportable for her to continue to live with him. She also petitioned for custody of their three young children along with her share in the succession of her late father, which Armant had apparently spent. The process was lengthy and complicated, lasting through the years of 1847, 1848 and 1849, as Armant continued to appeal the rulings in his wife’s favor.

The de la Vergnes and Armants both owned plantations and enslaved many individuals. The violence Terence Armant inflicted upon his wife was likely also experienced by the enslaved people in proximity to him. While Adele had some recourse under the law to address this abuse, the enslaved in her household did not.

LEFT: 938 Esplanade Avenue in 1939. Image courtesy of the Louisiana State Museum. RIGHT: Marie Adele de la Vergne (de Villere). Image courtesy of geni.com.

The significance of the de la Vergne family’s standing in support of Adele cannot be understated. Though women in Louisiana did have the right to divorce their husbands, such an act was uncommon, often unsuccessful, and certainly a source of scandal. Most families like the de la Vergnes would have pressured Adele to arrive at some arrangement with her husband in which they lived separately but continued to be married or demanded that she endure the abuse as part of her duties as a wife and mother. Alcée Fortier described the de la Vergnes as a family of “ancient chivalry,” and insisted that “none could look back on an ancestry more creditable.” Adele’s in-laws, the Armants, were an equally powerful and old family in possession of greater wealth than hers at the time of the suit.

The de la Vergnes had nothing to gain by supporting Adele, yet they remained loyal to her. In fact, they all testified on her behalf. In a rather exceptional occurrence for the 19th century, the abused woman’s family cared far more about her well being than the social mores of the time or how their standing in society might suffer. Madame de la Vergne, an elite widow and ardent Catholic, stood before the court and publicly stated that it was impossible for her daughter to live with a man who had been habitually mistreating her.

As Jules de la Vergne took his mother’s arm to exit the courtroom, Terence Armant approached with a heavy cane. He repeatedly attacked Jules until a blow glanced over him and struck Madame de la Vergne’s bonnet. Jules immediately placed his hand in his breast pocket and took out a dagger. The brothers-in-law grappled for a moment before Jules succeeded in stabbing Armant at least four times. Armant survived the attack, but his behavior was used as proof of his violent nature when the suit reached the Louisiana Supreme Court.

Advertisement

By 1850, Adele was safe and surrounded by family. She and her three sons were living with her mother and brother Jules in the Esplanade Avenue home, while Terence Armant resided at his family’s plantation upriver.

After her mother’s death in 1858 and the onset of the Civil War, Adele appears to have experienced financial setbacks and other challenges that forced her to return to Terence Armant. Armant had moved to Kentucky during the Civil War. She joined him there and had two more children with him before he was murdered during an altercation he instigated. Once again, Adele sought refuge in the Esplanade home now occupied by her brother Jules and family.

Adele de la Vergne Armant died of tuberculosis in 1877, leaving behind adult sons and a 14-year-old daughter named Julia. Julia remained in the extended family household with her Uncle Jules, cousins, their spouses and children. The family soon moved to St. Charles Avenue and also established a summer home in Covington. Perhaps influenced by her mother’s tragic experience, Julia never married. The Esplanade home still stands as a reminder of Adele’s bravery and her family’s loyalty.

Katy Morlas Shannon is the historian at Laura Plantation.

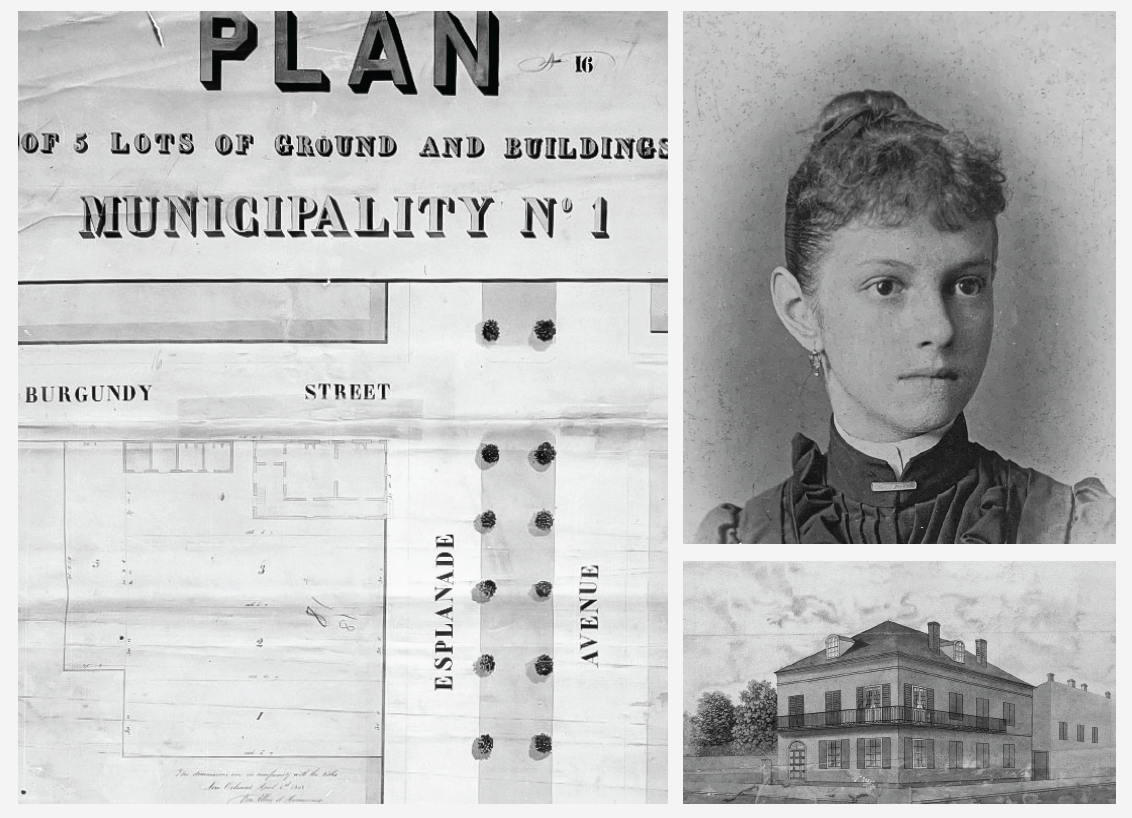

Left: A historic plan showing the Esplanade Avenue property. Image from the New Orleans Notarial Archives. Right top: Julia Armant. Image courtesy of geni.com. Right bottom: 938 Esplanade Ave. as depicted on the historic property plan. Image from the New Orleans Notarial Archives.

Advertisements