This story appeared in the February/March issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

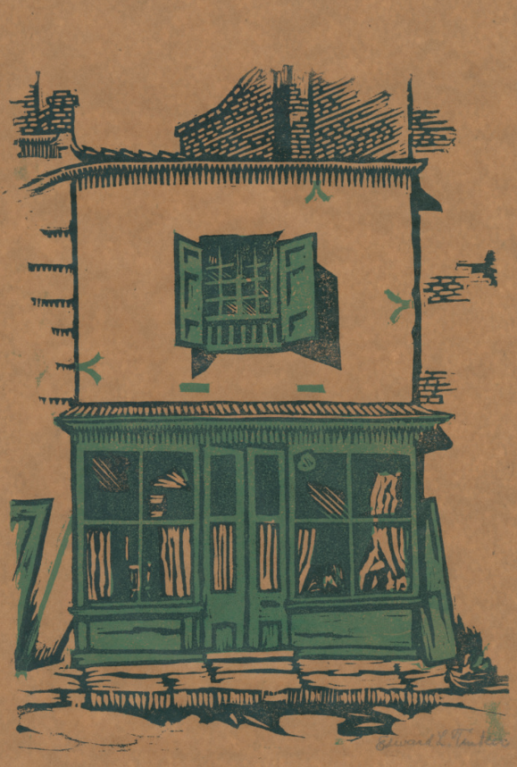

The building at 633 Royal St. in the Vieux Carré barely commands attention. It has no carriageway, nor cast-iron galleries to delight the eye. It’s tiny by comparison to neighboring buildings — just 14 to 15 feet wide. It has no ornamentation. In fact, the only element of the facade that bears notice is the second-floor window — just one —concealed by a shutter.

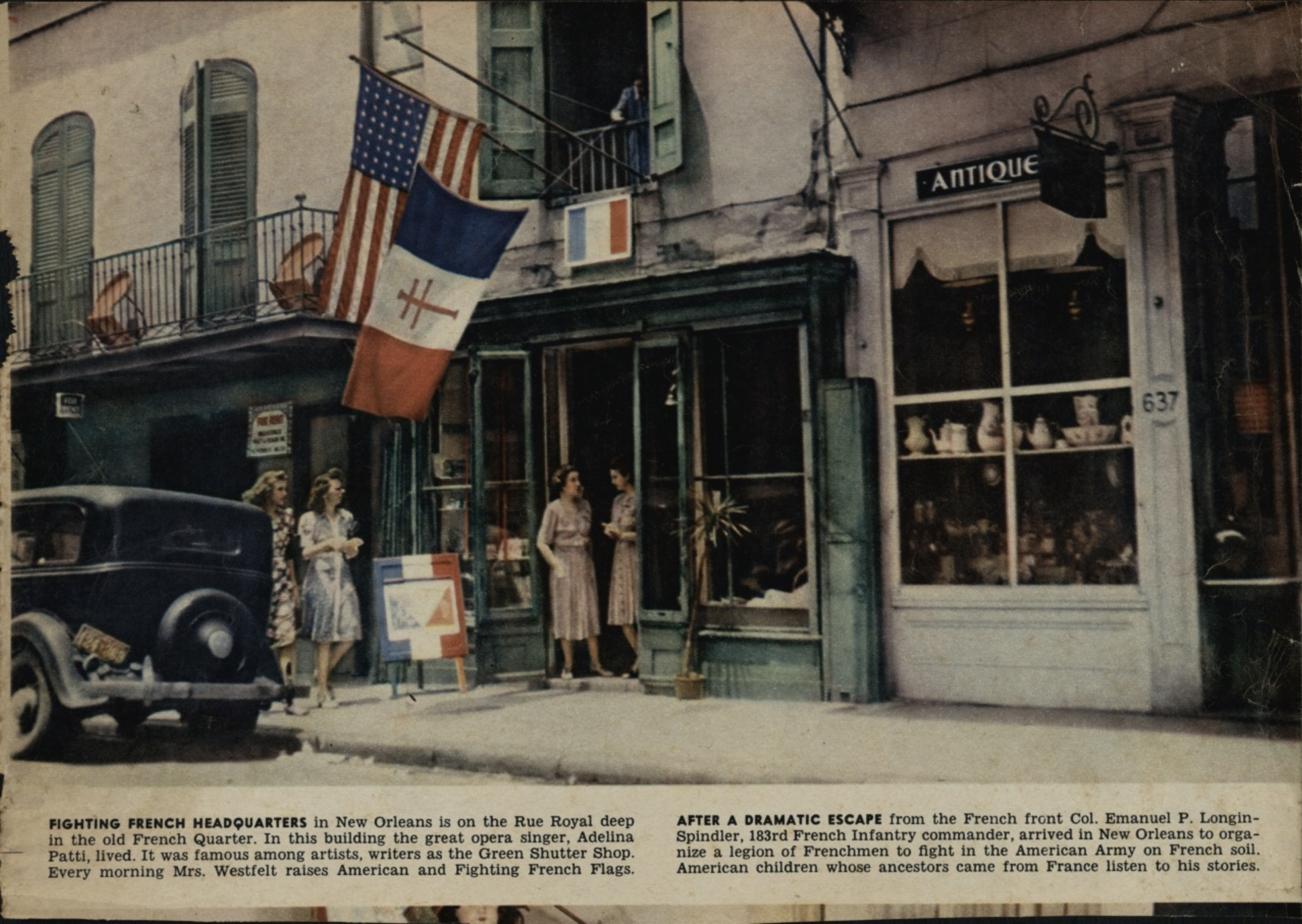

Despite its diminutive size, this building has played an outsized role in the culture of the French Quarter during the past 200 years. It has served as a home, an upholstery shop, a tearoom, an antiques store, headquarters of France Forever (an American organization supporting the French resistance fighters in World War II), a gathering place for Bohemian writers and artists, offices of the American Cancer Society, a pottery shop, a bookstore and a jewelry store.

It’s impossible to write about 633 Royal St. without discussing the Cavelier family and the other properties held by them in the 600 block of Royal Street. Although nearly every building in the Vieux Carré burned in the fire of 1788, the building at 627-31 Royal St. — immediately adjacent to 633 Royal St. — survived the next major blaze in the French Quarter in 1794.

The owner of 627-31 Royal St. at the time of the 1788 and 1794 fires was Antoine Dauphin Cavelier (1746-1826), a wealthy merchant of French heritage who, along with his sons Antoine Joseph (1774-1850) and Jean Baptiste Zenon (1776-1850), owned and developed much of the 600 block of Royal Street at the end of the 18th and first half of the 19th centuries.

In The French Quarter of New Orleans, author Jim Fraiser likened Antoine Dauphin Cavelier to Bernard Marigny and called him “a Frenchman of…extraordinary vintage…who, according to tradition, was a descendant of René-Robert Cavelier de la Salle, who had first claimed Louisiana for France in 1682.”

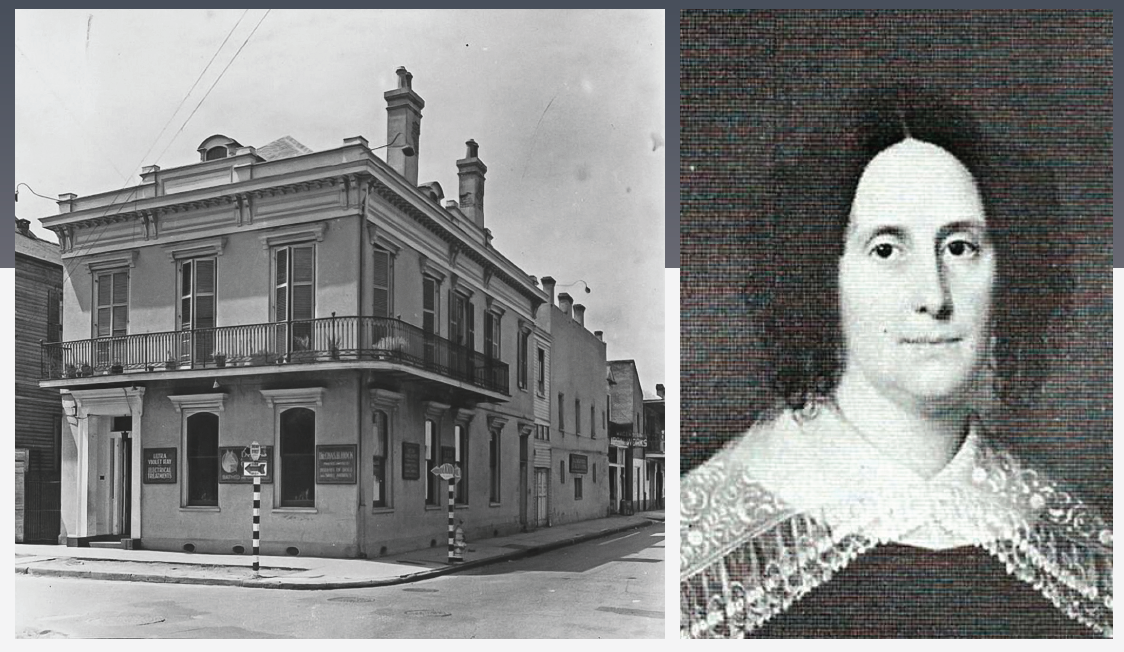

Photo 1: 633 Royal Street today. Photo by Liz Jurey. Photo 2: The Green Shutter in the 1920s or 1930s. Image courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection, The Collins C. Diboll Vieux Carré Digital Survey, 2-061-020.

After 627-31 Royal was destroyed in the 1788 fire, “Cavelier rebuilt his mercantile establishment on the spot in 1789, and it was one of two houses to survive the 1794 fire,” Fraiser writes, adding that the Spanish Governor Carondelet wrote in his report, “We managed to stop the fire when it reached the bank of the parochial church and the business house of Don Antonio Cavelier, which was almost in front of the house where it started.”

At the time of the 1788 fire, the lot at 633 Royal was occupied by a brick-between-post building (constructed prior to 1777), which was destroyed. Some time before 1807, when Antoine Joseph Cavelier acquired 633 Royal in a sheriff’s sale, a second structure was built there — “a small house recessed from the street” — and was present on the lot in 1807.

After acquiring 633 Royal at the sheriff’s sale, Antoine Joseph Cavelier merged the title of the property with that of 627-31 Royal St. He likely demolished the building that was recessed from the street and built the current structure after the 1807 acquisition and before 1817, when a transfer, noted in the Collins C. Diboll Vieux Carré Survey of The Historic New Orleans Collection (but not in the chain of title), describes a “new house — composed of a store, two rooms, a kitchen and a courtyard.” No doubt this is the structure at 633 Royal St. today.

Advertisement

In 1818, Antoine Joseph Cavelier sold 633 Royal St. and its neighboring property to Louise Foucher Poree but reacquired it from her heirs after her death 15 years later. In her 1833 succession, the property was described as “a main house facing Royal Street” (627-31 Royal) and “other buildings.”

Antoine Joseph Cavelier lived at 627-631 Royal St. in the Creole townhouse built in 1789 after the fire of 1788. Much later, in 1860-61, Adelina Patti, a well-known opera singer, stayed there, earning it the name “Patti’s Court.”

A few doors closer to Toulouse Street, Antoine’s brother, Jean Baptiste Zenon, president of the Banque d’Orleans, built a home for himself and his family in 1832 at 609-11 Royal St., designed by architects Gurlie and Guillot. Zenon’s home became the fabled Court of Two Sisters restaurant in the 1960s.

Zenon died in 1850 just seven months before Antoine. When Antoine Joseph Cavelier died in December 1850, he left an estate that included cash, land and buildings. His will, written in French and dictated to a notary, confirms his landholdings and wealth, and states that he also owned 35 esclavés, or enslaved people, who he leased to a man in Baton Rouge. The land holdings included 959 acres on Bayou Tunica in West Feliciana; several pieces of land near Opelousas; a large property on the Mississippi River in Missouri; Apple Island in the Pearl River near Natchez; and his Royal Street properties.

Photo 1: The Green Shutter courtyard, circa 1920. Image courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection, Gift of Mr. Boyd Cruise, Acc. No. 1958.85.173. Photo 2: Print of The Green Shutter by Edward Larocque Tinker, circa 1923. Image courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, Acc. No. 1966.6.6.

Some of the properties he had inherited from his late wife, Charlotte Sophie Boucher de Grand-Pre, the daughter of military and civic leader Charles Louis (in Spanish, Carlos Luis) Boucher de Grand-Pre, who served the Spanish crown as governor of the Baton Rouge District and of Spanish West Florida. He also served as lieutenant governor of the Natchez District and built two homes there: Concord (which burned in the early 1900s) and Hope Farm, which today is a bed and breakfast inn.

After the brothers’ heirs sold off the Royal Street properties, there were no Cavelier property owners in the 600 block of Royal Street for the first time in more than 70 years.

In the decades preceding their deaths, however, the brothers shared a unique perspective on their hometown of La Nouvelle Orleans. They were born to French parents in an era of Spanish rule of the Louisiana Territory (1762-1803), which is why Antoine is often written as “Antonio” and Jean Baptiste Zenon as “Juan Batista Zenon.”

Advertisement

When Spanish rule ended in 1803, they were briefly under the crown of France before the Louisiana Territory was sold to the United States that same year. After Louisiana became a state in 1812, they adapted to becoming American and fought against the British in Chalmette in 1815, Zenon as a colonel of the 2nd Regiment under Brigadier General Jean B. Labatut of the 1st Brigade, and Antoine as a major.

In their lifetimes, they were witnesses to every change of authority that New Orleans experienced, save for France’s secret ceding of the territory to Spain in 1762. What changes the two brothers must have witnessed.

The history of the block was subdued for almost another 70 years, until Martha Gasquet Westfeldt acquired 633 Royal St. in 1921. The daughter of Frank Gasquet and Louise Lapeyre, Martha Jefferson Celine Gasquet led a typical life of a wealthy and socially prominent New Orleanian, with trips to the Gulf Coast, North Carolina and Cuba all noted in the local papers.

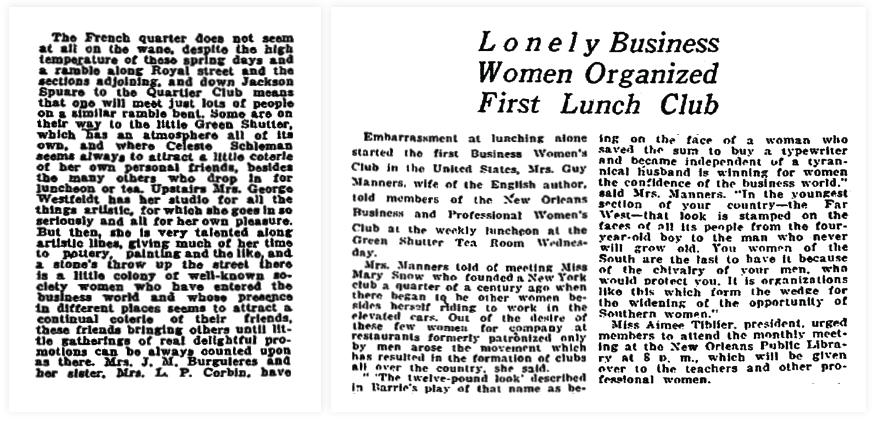

Left: The Times Picayune, April 16, 1922. Right: The Times Picayune. January 12, 1922.

She had married George Gustav Westfeldt, and they already had four children when Martha bought the building at 633 Royal. The purchase coincided with efforts to revitalize the French Quarter, where many buildings had become dilapidated, and tenements existed. It isn’t known what her motivation was to acquire the building, but her new venture, “The Green Shutter,” was a resounding success.

Gasquet Westfeldt established a coffeehouse, bookstore and tearoom there, as well as at 708-10 St. Peter St., a property she acquired in 1927. She linked the two by making an opening in the wall between the two courtyards.

The tearoom became a favorite location for deb parties, ladies’ luncheons and other events of polite society and soon was discovered by the Quarter’s Bohemian set: William Faulkner, Alberta Kinsey, Lyle Saxon, Morris Henry Hobbs, William Spratling, Sherwood Anderson and others.

Gasquet Westfeldt, who had studied art at Newcomb College, was a fine potter; she set up a kiln in the courtyard of the Green Shutter and made objects to sell in the shop. She was a charter member of the Arts and Crafts Club, which temporarily used the Green Shutter as its headquarters. She hosted exhibits of original artwork at the shop and donated generously to a variety of arts and civic causes. Thanks to her gifts to the New Orleans Public Library, patrons were offered the opportunity to borrow prints of works by well-known artists to take home and try out.

“That heathen crowd” — a phrase coined by poet Carl Carmer, meaning the Bohemian artists of the Quarter in the 1920s — made the Green Shutter their gathering place, inspiring poetry and newspaper articles likening it to Greenwich Village. But by the end of the 1920s, the Quarter was being “discovered,” and the “heathen crowd” had dispersed, some of them priced out of their old stomping grounds. Gasquet Westfeldt then turned her attention to a new venture as the leader of the Louisiana Women’s Committee, organized to oppose the political corruption of the Huey Long administration. She and her compatriots campaigned tirelessly and wrote many letters to the editors of the local newspapers before their efforts ended abruptly when Long was assassinated at the Louisiana Capitol in 1935.

Photo 1: Advertisement in The New Orleans Item. March 25, 1927. Photo 2: “For the Freedom of France” magazine clipping from between 1940-1945. Image courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection, Bequest of Mettha Westfeldt Eshleman, Acc. No. 2001-52-L.17. Photo 3: Telegram from Eugene Houdry to the 633 Royal Street Chapter of France Forever, 1942. Image courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection, Bequest of Mettha Westfeldt Eshleman, Acc. No. 2001-52-L.14.

Ever an activist, Gasquet Westfeldt served in the Red Cross Ambulance and Motor Corps in the first World War, whereby she transported German prisoners of war held in Louisiana. But it was during the second World War that the Green Shutter made headlines as the New Orleans headquarters of France Forever, a movement to support French fighters resisting the Vichy government in France. It morphed into the Free French Shop, a craft store that sold donated goods to raise funds for French and Belgian soldiers and their families. In her work, she also helped French merchant marines under the thumb of the Vichy regime to defect.

For her selfless work, Gasquet Westfeldt was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor by France and was awarded the Silver Medal of the Order of the Crown by Belgium.

Gasquet Westfeldt continued collecting goods for shipping overseas for several years after the war. She died in 1960. Her family held onto 633 Royal St. until 1991, when her daughter and heir, Ethel Jane Westfeldt Bunting, sold the building to NAG Ltd., doing business as Naghi’s. The company still owns the property and operates it as an art gallery and antiques shop.

It’s good to know that, according to the French Quarter Journal, the Green Shutter sign, an important relic of 633 Royal St., is still safely stored upstairs in the attic of the building, even to this day.

THE PRESERVATION RESOURCE CENTER’S HISTORY & LANDMARKS PLAQUE PROGRAM

provides an easy and beautiful way to commemorate the historic significance of your home, building or site.

The PRC conducts comprehensive building histories and offers bronze plaques to property owners who wish to celebrate their property’s history. Plaques and house histories are available for buildings or sites that are 50 years or older. Sites younger than 50 years will be considered if there is extraordinary historic significance associated with the place.

To purchase a house history or a historic marker, click here or call 504.581.7032. Plaques take at least six months to produce.

PRC History & Landmarks Plaque locations:

417-19 Calhoun St. • 579 Broadway St. • 7927 St. Charles Ave. • 2437 Fern St. • 4900 St. Charles Ave. • 3020 Prytania St. • 827 Ursulines Ave. • 616 Girod St. • 1717 Coliseum St.

Advertisements