This story appeared in the May issue of PRC’s Preservation in Print magazine. Interested in getting more preservation stories like this delivered to your door nine times a year? Become a member of the PRC for a subscription!

As a geographer in an architecture school, I often find myself making the unpopular argument that location has a devious way of subverting even the loftiest of design intentions. A house designed with all the latest sustainable and resilient components, for example, may end up neither if it is placed in a remote or hazardous location. A new amenity aimed to serve disadvantaged populations might end up displacing them if it is located in a neighborhood about to gentrify. And a beautiful design for an important program might end up a white elephant if it is built in an impractical space.

That last scenario nearly played out in 1837 on 1500 feet of Canal Street neutral ground spanning from present-day North Peters Street to Bourbon Street.

Every New Orleanian knows the best use for a neutral ground is as open land — grass and trees, maybe a statue or public art, perhaps streetcar tracks where appropriate, but rarely a building, much less five blocks of them. But at the time, merchants viewed Canal’s capacious median as an impediment to the commercial development of the artery, and flagged it as the reason why the streets of the upper French Quarter seemed to monopolize much of the retail action.

“Here one found the banks, insurance companies, exchanges, specialty retail stores, commodity brokers, wholesale warehouses, factors[,] bookshops, jewelry stores, and dry good emporiums,” wrote historian Joseph G. Tregle Jr. of upper Levee (now Decatur), Chartres, Royal and Bourbon streets. In 1835, visitor Joseph Holt Ingraham described Chartres Street in particular as “the ‘Broadway’ of New-Orleans[,] occupied almost exclusively by retail and wholesale dry goods dealers, jewellers, booksellers, etc…. I could almost realize that I was taking an evening promenade in Cornhill, so great was the resemblance.”

Advertisement

That’s the economic action Canal merchants wanted for their street, were it not for that muddy median.

Indeed, the boulevard had not originally been designed for such an apparent waste of space. It had been laid out in 1810, after New Orleans had petitioned the U.S. government that this terre commune (the commons left open as a firing line along the colonial fortifications) be recognized as city-owned land. That effort led to a March 3, 1807 Act of Congress, which confirmed the city’s claim to the commons, in exchange for its relinquishing of other disputed lands. The law also stipulated that, within the commons, a 60-foot-wide right-of-way would be reserved for a navigation channel connecting the Mississippi River with the Carondelet Canal, that channel dug in 1794 (today’s Lafitte Greenway) to access Bayou St. John and Lake Pontchartrain.

Within the interstice bordered by Common Street (named for the commons) and Customhouse Street (now Iberville), surveyor Jacques Tanesse laid out a series of new blocks, and united them with a grand axis 171 feet in width, including two sidewalks of 21 feet each, two roadways each 35 feet wide, and the canal bed at 59 feet.

It was a fine plan but for one major aspect: that shipping canal. Imagine a channel joining the ornery Mississippi with the malodorous backswamp, cleaving the city in half and forcing all uptown/downtown traffic to transit awkwardly over a series of narrow bridges high enough to allow schooners to pass beneath.

Worse yet, imagine if a high river compromised the lock, formed a crevasse, and sent a torrent of floodwaters down Canal Street toward Lake Pontchartrain. The difficulty of building a sufficiently strong lock, among other issues, led to years of delay, during which time the name “Canal Street” stuck for the canal-less street, and the 60 feet of space remained open.

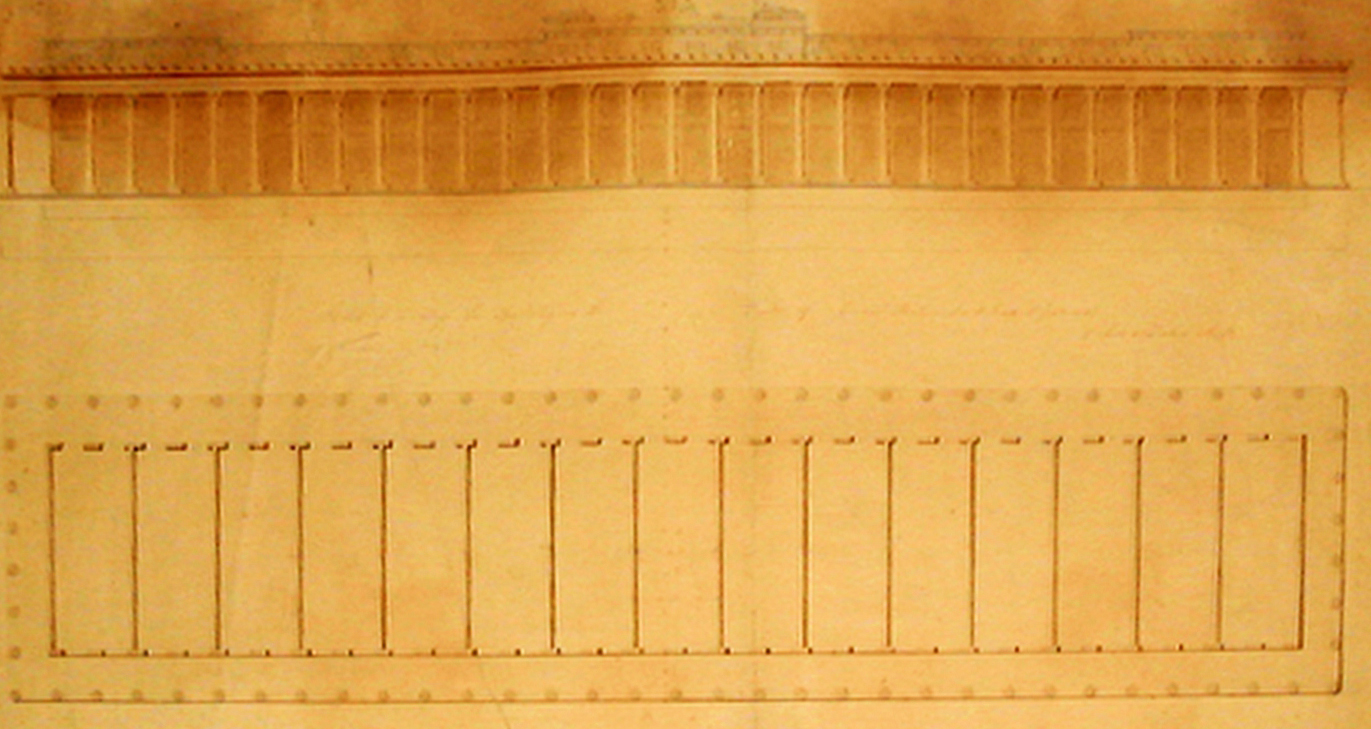

This sketch, dated Jan. 3, 1837, shows James H. Dakin’s vision for a market on the Canal Street neutral ground. Image from the James H. Dakin Collection at the New Orleans Public Library.

By the 1830s, Canal Street took on new cultural meaning. American dominion had attracted Anglo-American migrants, and they tended to settle upriver, apart from the Francophone Creole world below Canal Street. The two ethnic groups competed for political, economic and cultural power, and the discord got so bad that in 1836, the Louisiana Legislature, egged on by Anglo interests, subdivided New Orleans into three municipalities, each largely governing their own affairs.

Most people lived in the First and Second municipalities, the former being mostly Creole (the French Quarter and the Faubourg Tremé), the latter predominantly Anglo (the Faubourg St. Mary and the six faubourgs we now call the Lower Garden District). The obvious feature on which to draw the dividing line, for reasons of both urban geography and ethnic geography, was Canal Street, which thereafter became a demarcation of political geography.

It was in this era that a new term started circulating in the Anglophone vernacular, possibly inspired by the name for the demilitarized zone in southwestern Louisiana which recently existed between the United States and Spanish Mexico. That term was “neutral ground,” and formed something of a jocular reference to the capacious width of Canal Street vis-à-vis the seemingly intractable ethnic enmity on both sides.

Perfect place, thought some intrepid investors, for a 1,500-foot-long private marketplace.

Never mind that each municipality already had their own markets — the French Market and Tremé Market in the First; the St. Mary and Poydras in the Second — and that the ethnic antagonism might not make for a contented clientele. Never mind that neither municipality would want to permit a private emporium to compete with their own public markets. And even if they did, there was the uncertainty over jurisdiction: was Canal’s neutral ground in the First or the Second municipality? Or both? Could the space legally be leased and privatized?

Most vexing was the sheer impracticality of putting all that food retail — the meat, the blood, the water, the organic matter, the loading and unloading, not to mention the vermin — in the middle of the main metropolitan axis, forcing pedestrians to navigate across 35-foot-roadways while omnibuses, carriages and dray wagons went around it. Worse yet, the neutral ground, particularly in 1837, had terrible drainage problems, and became the butt of jokes for its swampy, frog-infested environs strewn with rubbish.

Advertisement

Unperturbed, project promoters commissioned an architect to draw up the plans, perhaps to demonstrate their resolve. They chose a rising star, James Dakin, who had made a name for himself in New York with the firm of Town, Davis and Dakin. In New Orleans, he partnered briefly with James Gallier Sr. and, among other things, designed the stupendous dome of the St. Charles Hotel.

On his own, or partnered with his brother Charles Dakin, James in this era also designed the Verandah Hotel, Merchants Exchange and Union Terrace. He was among the best Classical architects in the country, and, working as Dakin and Dakin, the firm pulled out all the stops for the great market emporium in the middle of Canal Street.

In a letter written 10 years later and quoted by Dakin biographer Arthur Scully Jr., James Dakin recalled that in January 1837, he had been “employed” by a group of “gentlemen,” among them financier Benjamin Story, to design “stores on the vacant space on the centre of Canal St. from New Levee St. to Bourbon St.” The wordage implied there would be five separate units, one per block, each 330 feet long and 55 feet across, with 15 stalls inside each unit and open-air arcades on either side, their columns within inches of traffic. Though skillfully executed stylistically, Dakin’s “Sketch of a Design for Building on the Center of Canal St., N.O., Dakin & Dakin,” now stored in the New Orleans Public Library’s James H. Dakin Collection, leave many site questions unanswered, namely conflicts between market activity and traffic flow.

Yet Dakin seemed confident in the promoters’ business arguments, which he deemed “based upon facts and not imaginary or speculative foundations.” His design, according to Scully, “shows a long colonnade with much the same feeling of the French Market on Decatur Street, but in a decidedly Greek Revival style,” with capitals of the Corinthian order, statuary, various Classical ornamentations, and a flat roof “accentuating the horizontal lines of the building.” It looked like something out of ancient Athens, and it would have been replicated fivefold over a quarter of a mile — quite a sight.

Advertisement

What derailed the project was, in Dakin’s words, “the commercial crisis of that year,” meaning the Panic of 1837. Investment dollars dried up, and a major expenditure on a speculative venture would have been doubly unwise. Another factor may have been legal: on Nov. 14, 1837, the First Municipality denied the right of the Orleans Navigation Company, operator of the Carondelet Canal (by this time known as the Old Basin Canal), “to make a canal in the centre of said Canal-Street,” as had been designated by Congress back in 1807. While it is unclear whether the resolution aimed to clear the way for the market, it indicated that other interests could be vying for the use of the neutral ground.

The market idea lingered for a few years, earning half-hearted support in the press. “A continuous row of neat white sheds…to turn the ‘Neutral Ground’ of Canal, or centre of Canal street, into some profitable purpose,” opined the Daily Picayune in July 1839, “would be quite an ornament to that part of the city, and cover up a variety of nuisances which have been a disgrace to that street for years.” But the same editorialist also flippantly suggested alternative, and perhaps equally profitable, uses for the neutral ground: building a gigantic ten-pin alley, or “farming the whole concern.”

In subsequent years, discussion of both the canal and market petered out in favor of simple drainage and pavement improvements. The reason: the broader economy had achieved what the market had been intended to do, which was to catalyze business activity on Canal Street. Over the course of the 1840s, retailers and merchants in the upper Quarter migrated over to Canal Street, where they found more space, better access and greater foot traffic, thanks to their own agglomeration. The three municipalities reconsolidated into one city in 1852, putting an end to that divisive and wasteful tripartite system. Fancy new department stores and theaters opened; streetcar lines were installed; and the Canal Street neutral ground became useful in the urban fabric. A market would have been superfluous, and a navigation canal disastrous.

In 1880, the German travel writer Ernst von Hesse-Wartegg, after exploring New Orleans and writing a thorough analysis of what he saw, described Canal Street as “the Broadway of New-Orleans,” the exact same metaphor that Joseph Holt Ingraham had used 45 years earlier to describe Chartres Street.

And it all happened because Canal Street had good economic geography all along, and needed neither a navigation canal nor a misplaced market to make it all work.

Canal Street, photographed here in 2015, was laid out in 1810 by surveyor Jacques Tanesse. He designed the space as 171 feet in width, including two sidewalks of 21 feet each, two roadways each 35 feet wide, and a canal bed — today’s neutral ground — at 59 feet. Photo by Richard Campanella.

Canal Street, photographed here in 2015, was laid out in 1810 by surveyor Jacques Tanesse. He designed the space as 171 feet in width, including two sidewalks of 21 feet each, two roadways each 35 feet wide, and a canal bed — today’s neutral ground — at 59 feet. Photo by Richard Campanella.

Richard Campanella is a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture and author of The West Bank of Greater New Orleans, Bourbon Street: A History, Bienville’s Dilemma and other books. Campanella may be reached through richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, or @nolacampanella on Twitter.

Advertisements